Diplopia Detective – Case 2

Welcome to the Journal of Medical Optometry’s Diplopia Detective, a series where we discuss interesting cases of diplopia using both a thoughtful and practical clinical approach. Diplopia is a complex problem with a broad spectrum of possible causes. It often requires a detective-like approach to rule out the more insidious pathologies that could be at play. By being a diplopia detective and systematically evaluating these patients, eye care providers are capable of making critical, challenging, and potentially sight- or life-saving diagnoses.

CASE REPORT

A 79-year-old male patient presented with diplopia when lying on his side for prolonged periods watching TV at night for about two months, which he reported resolved when covering either eye, or within a few minutes of returning to upright positioning. Systemic history was remarkable for diabetes and hypertension with an A1C of 6.1% within the previous three months and last blood pressure reading of 130/70. His ocular history was remarkable for having developed traumatic cataracts after significant trauma from falling off a roof. This was followed by extracapsular cataract extraction bilaterally, with lens decentration in the left eye greater than in the right for the last thirty years. Notably, the patient also reported that he could see a “silhouette” in the left eye ever since his cataract extraction. This was attributed to lens decentration (as reported in previous encounters with the patient), but this symptom had resolved within the past two months.

Entrance examination revealed 20/20 acuity in each eye. Pupils were reactive, with no evidence of an afferent pupillary defect; confrontation visual field testing was normal. Extraocular muscle evaluation appeared smooth and full bilaterally. Cover testing in five positions of gaze showed an eight-diopter esophoria in primary, up and left gaze, nine-diopter esophoria in down gaze, and ten-diopter esophoria in right gaze. This suggested a comitant esophoric posture which may be decompensating and causing diplopia due to a combination of age, evening fatigue, and non-primary gaze (lateral gaze due to prone position). Initial anterior segment examination appeared grossly unremarkable, and intraocular pressure was 16 mmHg and 15 mmHg in the right and left eye, respectively, with Goldmann tonometry.

The initial presentation suggested that the patient was experiencing a decompensating phoria or other physiologic senescent etiology, such as sagging eye syndrome. This was a compelling differential, given that both functional and structural changes occur with age and are known to result in variable distance esotropia.1,2 The first inclination for management was to provide education, recommend monitoring for progressive symptoms and consider prism or additional evaluation if symptoms progressed. However, as part of a thorough evaluation to rule out additional pathology, a dilated examination was done.

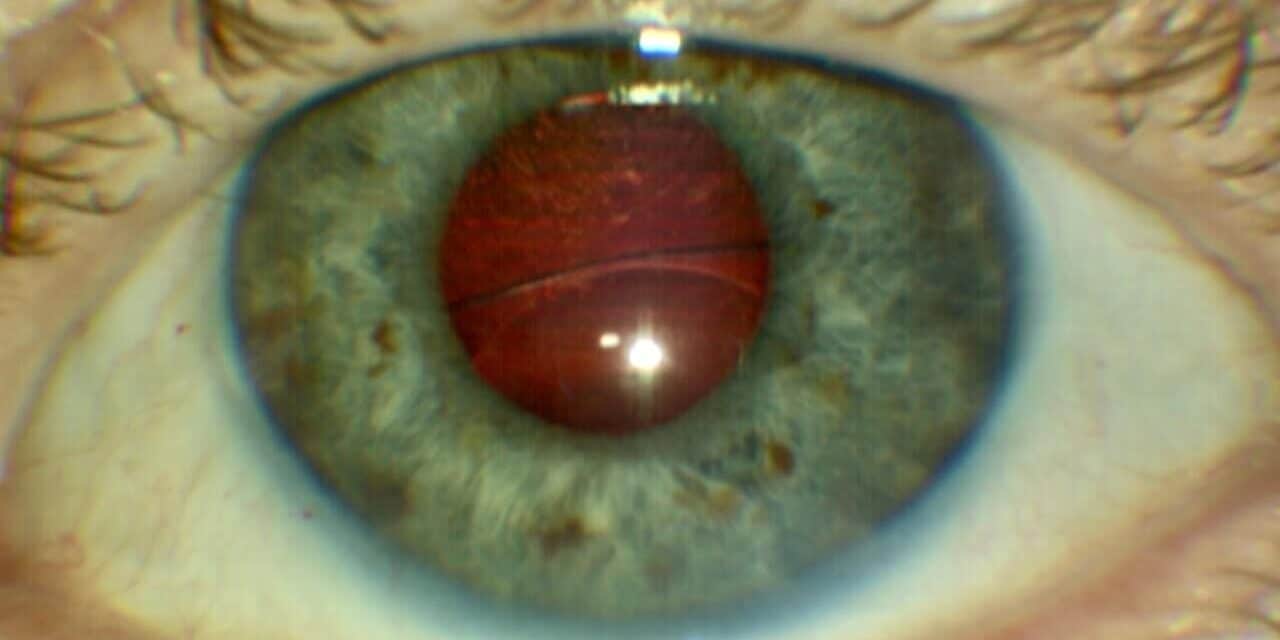

Upon dilation, the patient was found to have a significant intraocular lens (IOL) decentration and phacodonesis in the left eye. Where the IOL had previously been reported as mildly inferiorly decentered in the left eye, the superior edge of the one-piece IOL was sitting just above visual axis and was slowly mobile as the patient moved his eye. The patient was evaluated in different head positions, and the lens would slowly migrate with gravity and then return to center when his head was in primary position. Additional dilated exam findings were unremarkable, with healthy optic nerve, macula, and intact, attached retina 360° bilaterally. The patient was subsequently referred to a retina specialist where he underwent a successful PPV and lens exchange for a scleral sutured IOL in the right eye.

Figure 1. One-piece intraocular lens significantly displaced inferiorly with visible superior edge of the lens at mid-pupil.

DISCUSSION

Numerous factors can cause diplopia in an aging population. Many of these are benign causes associated with senescence, including convergence or divergence insufficiencies, eye movement latencies, and sagging eye syndrome.1,2 Acquired strabismus is the most common cause of diplopia in adults.3 A latent ocular misalignment that becomes symptomatic for diplopia is considered a decompensated deviation.4 The systematic review by Sunyer-Grau et al. reports that 75-95% of strabismus cases are comitant, non-restrictive, non-paralytic, or developmental.5 Knowing this prevalence, it can be easy to hastily classify what seems to be a typical presentation in a patient that fits both the clinical findings and demographic of these decompensating deviations.

Sagging eye syndrome was specifically considered due to the postural relationship of the patient’s symptoms. Another age-related cause of strabismus, sagging eye syndrome presents with esotropia, is often accompanied by blepharoptosis, and variably with superior sulcus defects or limited supraduction.2 Cioplean et al. discuss that there are multiple documented age-induced eso deviations, such as divergence palsy and “age-related distance esotropia (ARDE)” that are likely all manifestations or variant descriptions of sagging eye syndrome.2 Connective tissues lose elasticity with time, which results in muscle slippage and elongation.2 From an ocular standpoint, the pulley system of the lateral rectus is susceptible to this phenomenon, which results in an esophoric ocular posture.2 Possibly, this laxity caused by sagging eye syndrome could be exacerbated by gravitational changes of side-lying or prone positioning. However, it is important to consider the details of the case and the patient’s relevant ocular history so as not to miss a masquerading condition. This condition can be confirmed by MRI, but until that point, it is a diagnosis of exclusion.

Numerous reviews and analyses have reported an increase in the frequency of late intraocular lens displacement following even non-complicated cataract surgery.6-8 Late lens dislocation is the second most common long-term complication in all cataract surgeries, even when excluding trauma as an independent risk factor for lens dislocation.6 A 2017 literature review by Ascaso et al. found that around 1.7% of cataract surgeries resulted in IOL displacement after 25 years, and 90% of these had a predisposing factor for zonular weakness.7 The risk factors for late dislocation included pseudoexfoliation (50% of cases), trauma, high myopia, retinitis pigmentosa, diabetes, atopic dermatitis, connective tissue disorder, previous vitreoretinal surgery, and history of acute angle closure glaucoma.7

What initially appeared to be a simple decompensating esophoria on entrance testing proved to be more complicated when the dilated exam uncovered lens dislocation masquerading as a late, comitant misalignment. This case demonstrates the importance of obtaining a thorough patient history, reviewing pertinent ocular history, and performing a dilated evaluation, even in cases that appear straightforward, to prove that a diagnosis of exclusion is just that.

Clinical Pearls for Catching the Culprit

- More than 75% of strabismic deviations are comitant, non-restrictive, developmental, or senescent in nature.

- Sagging eye syndrome is an evolving topic, is likely an underdiagnosed phenomenon contributing to age-related diplopia, and can be supported by other clinical associations and CT/MRI imaging.

- Age-related or decompensated diplopia should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion. Symptoms, thorough history, and a dilated examination will help guide the ultimate diagnosis and treatment in these patients.

- Trauma is a significant factor in ocular history and can have lasting impacts on ocular structure integrity even decades after the initial injury occurred.

REFERENCES

- Godts D, Mathysen DGP, Distance esotropia in the elderly. British Journal of Ophthalmology 2013;97:1415-1419. https://bjo.bmj.com/content/97/11/1415

- Cioplean D, Nitescu Raluca L. Age related strabismus. Rom J Ophthalmol. 2016;60(2):54-58. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC5711365/

- Gräf M, Lorenz B. How to deal with diplopia. Revue Neurologique. 2012;168(10):720-728. doi:10.1016/J.NEUROL.2012.08.001

- Ali MH, Berry S, Qureshi A, Rattanalert N, Demer JL. Decompensated Esophoria as a Benign Cause of Acquired Esotropia. Am J Ophthalmol. 2018;194:95-100. doi:10.1016/j.ajo.2018.07.007

- Sunyer-Grau B, Quevedo L, Rodríguez-Vallejo M, Argilés M. Comitant strabismus etiology: extraocular muscle integrity and central nervous system involvement-a narrative review. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2023 Jul;261(7):1781-1792. doi: 10.1007/s00417-022-05935-9. Epub 2023 Jan 21. PMID: 36680614; PMCID: PMC10271888.

- Kintzinger K, Rothaus K, Faatz H, et al. Inzidenz und Risikofaktoren der späten Hinterkammerlinsendislokation [Incidence and risk factors of late intraocular lens dislocation]. Ophthalmologie. 2025;122(8):625-631. doi:10.1007/s00347-025-02240-8

- Ascaso FJ, Huerva V, Grzybowski A. Epidemiology, Etiology, and Prevention of Late IOL-Capsular Bag Complex Dislocation: Review of the Literature. J Ophthalmol. 2015;2015:805706. doi:10.1155/2015/805706

- Gimbel HV, Condon GP, Kohnen T, Olson RJ, Halkiadakis I. Late in-the-bag intraocular lens dislocation: incidence, prevention, and management. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2005;31(11):2193-2204. doi:10.1016/j.jcrs.2005.06.053

Dr. Carr is a 2016 PCO graduate and completed residency in 2017 at the Wilmington VA Medical Center in Wilmington, DE. She returned on staff in Wilmington in 2019 and is now the student externship coordinator. She has an affinity for all things ocular disease, especially glaucoma, retinal disease, and neuro.