Ocular Sequelae of Trigeminal Neuralgia Following Complicated Oral Surgery: A Case Report

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

The trigeminal nerve is a crucial cranial nerve responsible for sensation in various areas of the face, including the cornea. Disruption of the trigeminal nerve through surgical interventions can lead to trigeminal neuralgia and severe ocular complications, significantly impacting a patient’s quality of life and potentially threatening their vision.

CASE REPORT

This case report describes a patient who developed severe trigeminal neuralgia following dental surgery on the right side of her mouth. As part of treatment for the neuralgia, she underwent a right-sided craniotomy for microvascular decompression of the trigeminal nerve. Following the procedure, she developed a combination of corneal neuralgia and neurotrophic keratitis in her right eye, which presented management challenges and resulted in a lengthy recovery process.

CONCLUSION

This case report highlights the significance of understanding neuralgia and ocular consequences resulting from oral surgical interventions. We aim to discuss the specific challenges presented, diagnostic evaluation, and outline the various management strategies for this unique case. Keywords: neurotrophic keratitis, trigeminal neuralgia, microvascular decompression

INTRODUCTION

The maxillofacial and oral region is a complex network of nerves, blood vessels, and tissues essential for facial sensory and motor functions. The central element of this network is the trigeminal nerve, which provides sensory innervation to several regions including the face, oral cavity, cornea, upper eyelid, conjunctiva, and lacrimal gland. The trigeminal nerve is divided into three main branches: the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular branches.1 Common dental procedures, like molar and wisdom tooth extractions, carry certain complexities due to their proximity to the branches of the trigeminal nerve. The extraction process involves careful manipulation of nearby tissues, which may unintentionally damage the branches of the trigeminal nerve. The close anatomical relationship between dental structures and the nerve branches heightens the risk of damage during routine dental interventions.2 Disruption of the trigeminal nerve can lead to problems, including trigeminal neuralgia, which is often characterized by short-lasting, severe facial pain that can become chronic.3 First-line treatment for patients experiencing trigeminal neuralgia is anticonvulsant medications, such as carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, that block nerve firing. When treatment with oral medications does not provide long-term relief or attacks continue to become more frequent or increase in intensity, surgical intervention may be indicated. Microvascular decompression is the first-line surgical treatment for patients with trigeminal neuralgia.3 The trigeminal nerve also innervates the cornea. Neurotrophic keratitis is characterized by reduced or complete loss of corneal sensation. This condition leads to a breakdown of the epithelial layer, delayed and impaired healing, and in severe cases, the development of corneal ulcers, melting, and perforation.4 This case describes a patient who previously had trigeminal neuralgia after right-sided dental work was performed. After the dental procedure, she experienced episodes of severe pain on the right side of her face that were originally well-managed by oral oxcarbazepine to treat trigeminal neuralgia. However, her symptoms worsened, and as a result, she underwent a right open skull base craniotomy for microvascular decompression of the trigeminal nerve. She later developed corneal neuralgia and neurotrophic keratitis in her right eye.

CASE REPORT

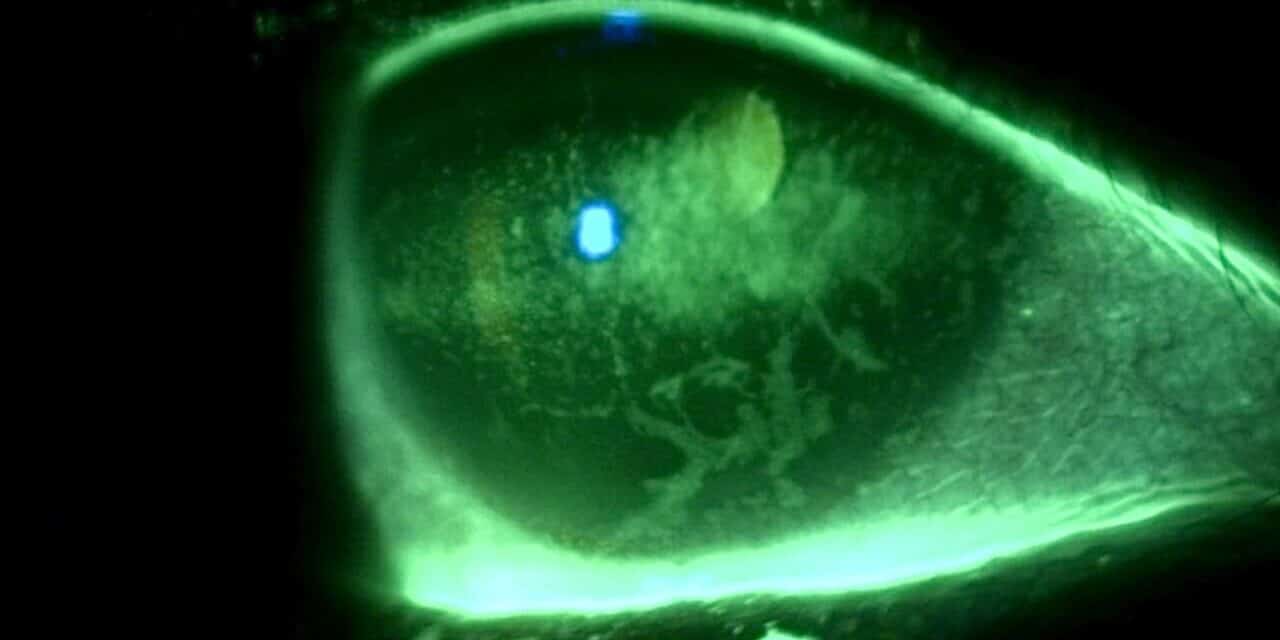

A 44-year-old female established patient was referred to the specialty anterior segment clinic for an evaluation due to unusual symptoms. She described a feeling of “a cold suction cup” on her right eye. The pertinent ocular history of the patient included decreased vision in her left eye due to optic atrophy from a childhood cystic lesion compressing the left optic nerve. There was no other pertinent medical or ocular history. Her surgical history included dental surgery, specifically a right upper impacted wisdom tooth extraction performed five years prior. The patient reported that a nerve was affected during the procedure and that she experienced severe pain on the right side of her face soon after the procedure. The intense pain continued for five years and was unsuccessfully treated with oral medications. The patient underwent a right-sided open skull base craniotomy for microvascular decompression of the trigeminal nerve to treat the trigeminal neuralgia. The patient reported experiencing right-sided facial numbness, intermittent blurry vision, and an uncomfortable right eye, with the inability to tear in the right eye soon after the procedure. Upon ocular examination, best-corrected visual acuity was 20/40 in the right eye, while the left eye showed no light perception. The left eye vision was stable, but her right eye vision had been 20/20 in prior eye exams. The right pupil was round and reactive to light, and a 4+ afferent pupillary defect was detected in the left eye, which was attributed to the left optic atrophy which was present since childhood. Confrontation visual field testing found a full-to-finger-count vision in the right eye, and the patient could not perform the test with her left eye. The sensitivity of the trigeminal nerve was assessed using a wispy cotton tip applied to the patient’s face and cornea. The patient was able to feel the cotton wisp on the left side of her face and cornea. However, she reported no sensation when the wisp was moved to the right side of her face (forehead, cheek) and cornea. She had some sensation on the lower right jaw. Slit lamp findings showed an intrapalpebral oval band of significant epithelial keratitis in the right eye, which stained with fluorescein but not with Rose Bengal. The stroma was intact and unremarkable. There was no keratitis noted in the left eye. A Schirmer’s test yielded results of 5 mm for the right eye and greater than 15 mm for the left eye. An InflammaDry test, which evaluates MMP9 levels in the tear film, was performed, yielding positive results in both eyes. Additionally, the proparacaine challenge test was performed, which did not improve her symptoms of a “suction cup” sensation. Intraocular pressures were within normal limits. A dilated fundus examination was unremarkable in the right eye and revealed a longstanding pale left optic nerve. A stage 2 neurotrophic keratitis was diagnosed in her right eye with a component of neuropathic pain. Multiple treatment options were discussed, including the placement of an amniotic membrane in the right eye. However, the patient was hesitant to proceed with this option since it was her only seeing eye. Cenegermin-bkbj 0.002% was prescribed to be used six times a day for eight weeks to address the neurotrophic keratitis in the right eye. Regular use of preservative-free artificial tears, spaced out at least 15 minutes with the cenegermin, was advised.

After starting the cenegermin-bkbj 0.002%, she was followed at four weeks and again at eight weeks. There was no improvement in her symptoms on follow up, and the “suction cup” sensation persisted. Vision remained 20/40 in her right eye, and corneal sensitivity remained absent in the right eye. The epithelial defects persisted with some improvement in the density of the epithelial breakdown. Although a second course of cenegermin was considered, the patient declined treatment continuation. A six-month dissolvable punctal plug was inserted in the right lower lid punctum to manage her ocular surface, and 20% autologous serum drops were added to use QID OD. A preservative-free artificial tear gel drop every two to four hours and a lubricating ointment at night in the right eye were also recommended. Although a fitting for a scleral contact lens was considered, it was ultimately not pursued. This case presentation was particularly concerning because she had only one functioning eye. She was referred to a corneal specialist for evaluation for corneal neurotization. The corneal specialist agreed to proceed with the neurotization; however, the procedure could not be performed due to insurance issues. The patient was kept on the same treatment of autologous serum, preservative-free artificial tears, and lubricating ointment. She was monitored regularly for six months, during which her symptoms of a “suction cup” sensation persisted, along with a stable epithelial keratitis.

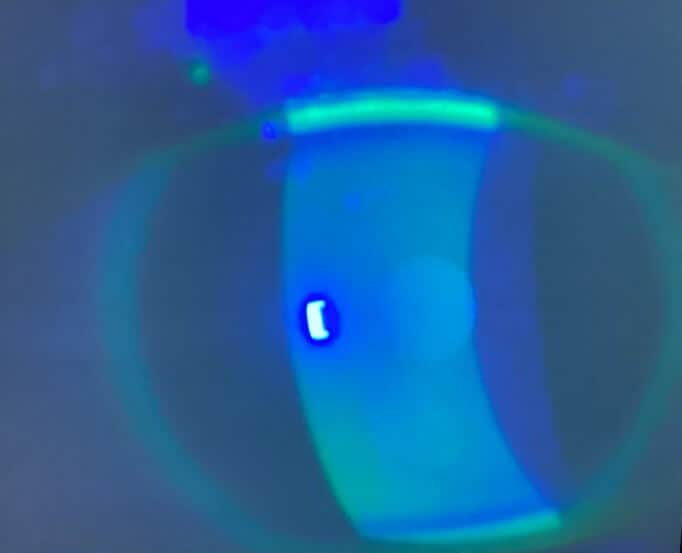

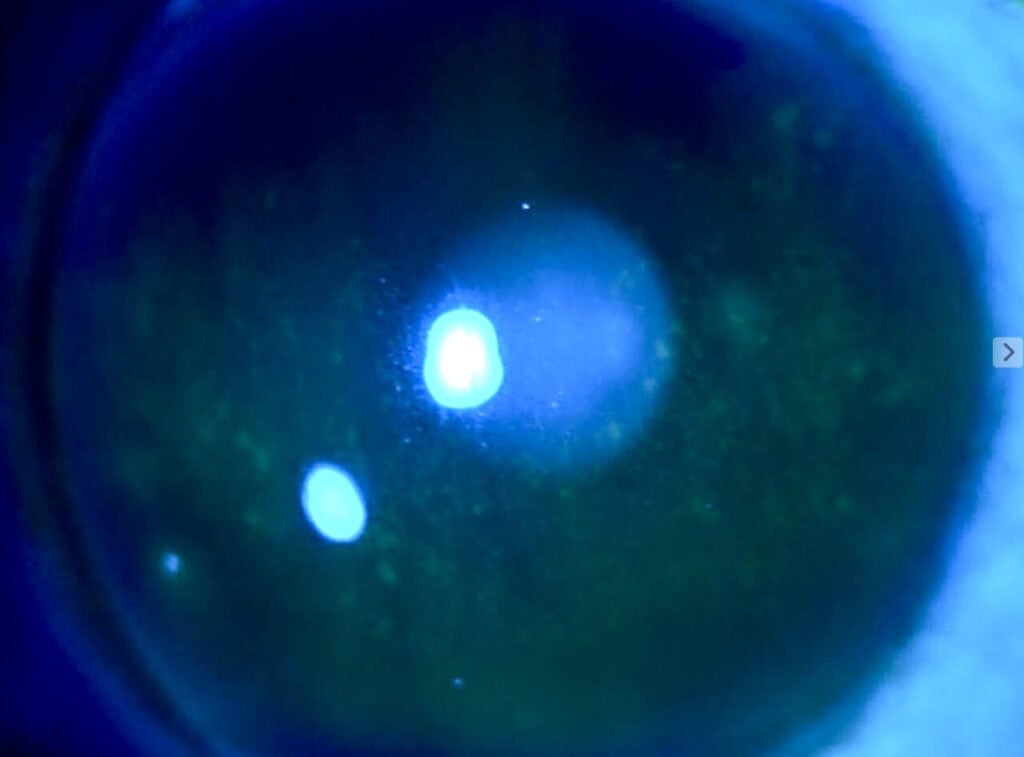

Figure 2. Corneal findings 6 months after treatment for eight weeks with cenegermin-bkbj and subsequent autologous serum.

One year later, she reported that she no longer experienced the “suction cup” sensation in her right eye and a significant improvement in her quality of life. Her vision improved to 20/20 in the right eye, and slit lamp examination revealed a clear right cornea with no fluorescein staining. Her neurotrophic keratitis had completely resolved. She was maintained on 20% autologous serum drops QID in the right eye.

DISCUSSION

Trigeminal neuralgia is typically described as a brief and intense facial pain. This disorder affects the fifth cranial nerve, which consists of three branches: the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular.4 Trigeminal neuralgia can affect one or more branches of the trigeminal nerve at the same time. The ophthalmic nerve (V1), the smallest of the three branches, is purely sensory and provides sensation to the scalp, forehead, eye, and nose. Notably, it contributes to the sensations of the ciliary body, iris, lacrimal gland, conjunctiva, and cornea. The maxillary nerve (V2) is also a sensory branch that supplies the area below the eye and above the mouth. Meanwhile, the mandibular nerve (V3), the largest branch, contains both sensory and motor components. The sensory portion of the mandibular nerve conveys sensations from the lower third of the face, the floor of the mouth, the jaw, and the tongue. Its motor portion primarily innervates the muscles involved in mastication.5 The trigeminal nerve, which serves as a major sensory nerve, plays a critical role in oral and facial sensations. Compression or injury to this nerve can lead to trigeminal neuralgia and neuropathic pain, causing symptoms such as persistent pain and changes in sensation. Because the trigeminal nerve also has a motor function that controls the mastication muscles, the effects of nerve compression may have functional complications such as difficulty with chewing and speaking. Especially for clinicians engaged in oral and maxillofacial procedures, it is crucial to thoroughly understand the complex anatomical relationships and potential complications associated with nerve compression. Research indicates that the incidence of nerve damage complications following tooth manipulation is low, at less than 1%. However, approximately one-third of patients who experience nerve damage do not fully recover. Therefore, early diagnosis of the cause of neuropathy can lead to better treatment outcomes. Symptoms of trigeminal neuralgia can often be confused with a toothache, underlining the necessity for objective evaluations of all patients showing signs of trigeminal nerve damage, both prior to and following treatment.6 Maxillofacial procedures are just one cause of trigeminal neuralgia. Trigeminal neuralgia’s primary cause is trigeminal nerve compression at the root entry by the superior cerebellar artery.6 Other potential causes include compression from an adjacent aneurysm, arteriovenous malformation, tumor, or abnormalities such as demyelinating plaques associated with multiple sclerosis.5 The lifetime prevalence of trigeminal neuralgia is estimated to range from 0.16% to 0.3%, while the annual incidence varies between 4 and 29 cases per 100,000 person-years. This condition is more prevalent in women than in men, with a female-to-male ratio of 3:2. The incidence of trigeminal neuralgia increases with age, with a mean age of onset between 53 and 57 years, and a range of 24 to 93 years in adult populations.3 The primary treatment for patients experiencing trigeminal neuralgia is the use of anticonvulsant medications. These medications, such as carbamazepine and oxcarbazepine, help block nerve firing. Trigeminal nerve blocks may be considered; however, they may offer only temporary relief. Common everyday activities such as eating, shaving, and exposure to wind and cold can be triggers. If the painful attacks become more frequent or intense and long-term relief is not achieved, surgical intervention may be necessary. In such cases, microvascular decompression is the first-line surgical treatment for trigeminal neuralgia.3 The most common etiology of trigeminal neuralgia is compression from a blood vessel. Microvascular decompression is an open surgical approach where a surgeon skillfully moves the superior cerebellar artery away from the nerve, which often alleviates the pain. While microvascular decompression is considered an invasive surgery, it has an approximately 80% success rate and often causes the least damage to the trigeminal nerve while providing the longest pain-free periods and without the need for permanent oral medications.7 Although rare, neurotrophic keratitis can occur as a secondary consequence after performing microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. Data support an incidence of 2.8% of neurotrophic keratitis in patients who have undergone surgical trigeminal neuralgia procedures.8,12 Corneal nerves, which are supplied by the trigeminal nerve, play an important role in maintaining corneal epithelial integrity, proliferation, and wound healing. Not only is there a reduction in lacrimation due to the trigeminal nerve and its connection with the facial nerve to innervate the lacrimal gland, but it is thought that damaged corneal sensory nerves can lead to changes in neuromodulators that can cause impairment in mitosis of epithelial cells that ultimately lead to epithelial breakdown. As a result, the corneal epithelium becomes thinner, leading to intracellular swelling, loss of microvilli, and an abnormal production of the basal lamina. The morphological changes ultimately lead to the development of recurrent or persistent epithelial defects, which can progress to corneal ulceration, melting, and perforation.12 Treatment and management of neurotrophic keratitis is crucial. In any stage of neurotropic keratitis, lubrication with preservative-free artificial tears is important. In later stages, where corneal melting or recurrent epithelial defects occur, collagenous inhibitors and antibiotics may be added to the treatment plan. Studies show that topical nerve growth factors, such as cenegermin-bkbj 0.002%, autologous serum eye drops, amniotic membranes, and therapeutic contact lenses, can be used effectively to treat neurotrophic keratitis. Cenegermin-bkbj 0.002% is the first FDA-approved therapeutic eye drop used to treat neurotrophic keratitis by fostering healing of the cells on the corneal surface, promoting tear secretion, and improving the function of the nerves in the cornea.4 The REPARO trial was a multicenter, randomized, double-masked, vehicle-controlled trial, and looked at the treatment of moderate to severe neurotrophic keratitis using recombinant human growth factor, cenegermin. After eight weeks of treatment, 74.5% of patients had attained corneal healing (defined as less than 0.5 mm of staining) as compared to 43.1% in the vehicle-controlled group. Of the patients in the cenegermin group, 96% remained healed and had no recurrence at 48 or 56 weeks.10 It is important to inform patients that while treatment with cenegermin may be successful, it is not guaranteed. When the cornea fails to heal properly despite various medical treatments, surgery may be considered. Corneal neurotization is a surgical procedure designed to restore corneal sensation via transplantation of healthy sensory nerves onto the cornea. Typically, nerves such as the supratrochlear, supraorbital, infraorbital, or sural nerves (found in the lower leg) are used, depending on the patient’s condition and the surgeon’s preference. This surgery typically requires a collaborative approach involving multiple specialties.14 Independent of treatment options, spontaneous recovery of sensory nerves is possible, although it is often slow and may be incomplete. The severity of a nerve injury significantly affects spontaneous recovery; generally, the less severe the injury, the more likely spontaneous improvement occurs. Types of damage can include stretching, compression, or laceration of the nerve. Inflammation may also lead to temporary dysfunction, which can resolve over weeks and months.13 Nerve damage and inflammation leading to neurotrophic keratitis may also result in corneal neuropathic pain.11 Corneal neuropathic pain, also known as corneal neuralgia, is typically caused by damage to the corneal nerves. It is characterized by chronic pain without active signs of corneal damage. Symptoms can include burning or cold sensations, photophobia, pain, aching, pulling, and a foreign body sensation. This patient’s neuropathic pain manifested as a “cold suction cup” sensation. In addition to neurotrophic keratitis and ocular surface inflammation, there are multiple conditions that can cause a symptom like this, such as prior ocular surgeries and ocular surface disease. Corneal neuralgia can also occur after trigeminal nerve decompression surgery due to potential aggravation of the ophthalmic division of the trigeminal nerve. The pain results from abnormal nerve regeneration and increased nerve sensitivity, leading the brain to misinterpret signals and perceive pain even in the absence of an active insult. Corneal neuralgia can be severely debilitating and significantly impact quality of life. The pain experienced by the patient can be more pronounced than the clinical signs. The proparacaine challenge test and visualization of corneal nerves with in vivo confocal microscopy are helpful in the diagnosis. Treatment options include autologous serum drops, topical steroids, and oral medications for pain management.15

CONCLUSION

This unique case involves a patient who developed trigeminal neuralgia after a dental procedure and subsequently underwent microvascular decompression surgery. Unfortunately, complications led to a combination of corneal neuralgia and neurotrophic keratitis. This case was particularly concerning because the patient was functionally monocular, and her only functional eye was affected. After eighteen months of symptom onset, she finally experienced a resolution of her symptoms and her keratitis with aggressive topical treatments. Both the pharmaceutical treatments and the eventual spontaneous recovery may have contributed to the resolution of her neuropathic symptoms and neurotrophic keratitis. This case report highlights the importance of understanding the relationship between oral surgical procedures and their potential effect on the trigeminal nerve.. It discusses challenges, diagnostic evaluations, and outlines various management strategies for corneal neuralgia. It is vital to enhance understanding of corneal neuralgia and neurotrophic keratitis and their treatment options to ensure optimal outcomes for similar cases in the future. Written informed consent was obtained for identifiable health information included in this case report, and no identifiable health information was included in this case report.

REFERENCES

- Walker H, HALL W, Hurst J. Chapter 61 Cranial Nerve V: The Trigeminal Nerve. In: Clinical Methods: The History, Physical, and Laboratory Examinations. 3rd Edition. 3rd ed. LexisNexis UK; 1990.

- Hillerup S. Iatrogenic injury to oral branches of the trigeminal nerve: records of 449 cases. Clin Oral Investig. 2007;11(2):133-142. doi:10.1007/s00784-006-0089-5

- Lambru G, Zakrzewska J, Matharu M. Trigeminal neuralgia: a practical guide. Pract Neurol. 2021;21(5):392-402. doi:10.1136/practneurol-2020-002782

- Feroze KB, Patel BC. Neurotrophic Keratitis. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

- Bendtsen L, Zakrzewska JM, Heinskou TB, et al. Advances in diagnosis, classification, pathophysiology, and management of trigeminal neuralgia. Lancet Neurol. 2020;19(9):784-796. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(20)30233-7

- Rehman A, Abbas I; Alamgir, Ghous SM, Ahmad N, Ahmad A. Association Between Trigeminal Neuralgia And Unnecessary Tooth Extraction. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2021;33(1):116-119.

- Hannan C, Shoakazemi A, Quigley G. Microvascular Decompression for Trigeminal Neuralgia: A regional unit’s experience. Ulster Med J. 2018;87(1):30-33.

- Zhang, X., Li, Y., Zhou, M. et al. Microvascular decompression in trigeminal neuralgia with the offending artery transfixing the nerve: a case report. BMC Neurol 22, 244 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12883-022-02765-4

- Shankar Kikkeri N, Nagalli S. Trigeminal Neuralgia. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-.

- Bonini S, Lambiase A, Rama P, et al. Phase II Randomized, Double-Masked, Vehicle-Controlled Trial of Recombinant Human Nerve Growth Factor for Neurotrophic Keratitis. Ophthalmology. 2018;125(9):1332-1343. doi:10.1016/j.ophtha.2018.02.022

- Yavuz Saricay L, Bayraktutar BN, Kenyon BM, Hamrah P. Concurrent ocular pain in patients with neurotrophic keratopathy. Ocul Surf. 2021 Oct;22:143-151. doi: 10.1016/j.jtos.2021.08.003. Epub 2021 Aug 17. PMID: 34411735; PMCID: PMC8560561

- Gurnani B, Feroze KB, Patel BC. Neurotrophic Keratitis. [Updated 2025 Mar 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431106/

- Shaheen BS, Bakir M, Jain S. Corneal nerves in health and disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2014 May-Jun;59(3):263-85. doi: 10.1016/j.survophthal.2013.09.002. Epub 2014 Jan 23. PMID: 24461367; PMCID: PMC4004679.

- Saini M, Kalia A, Jain AK, Gaba S, Malhotra C, Gupta A, Soni T, Saini K, Gupta PC, Singh M. Clinical outcomes of corneal neurotization using sural nerve graft in neurotrophic keratopathy. PLoS One. 2023 Nov 28;18(11):e0294756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0294756. PMID: 38015881; PMCID: PMC10684005.

- Watson SL, Le DT. Corneal neuropathic pain: a review to inform clinical practice. Eye (Lond). 2024 Aug;38(12):2350-2358. doi: 10.1038/s41433-024-03060-x. Epub 2024 Apr 16. PMID: 38627548; PMCID: PMC11306374.