Primary CNS Lymphoma Presenting With Confusion and Visual Field Deficits

Welcome to the “Neuro Nuggets” column within the Journal of Medical Optometry (JoMO)! This column aims to make neuro-ophthalmic disease more approachable by blending real-world clinical cases with evidence-based medicine. The patient in this edition’s column demonstrates the potential for CNS lymphoma to manifest with visual deficits. Enjoy!

Case Presentation

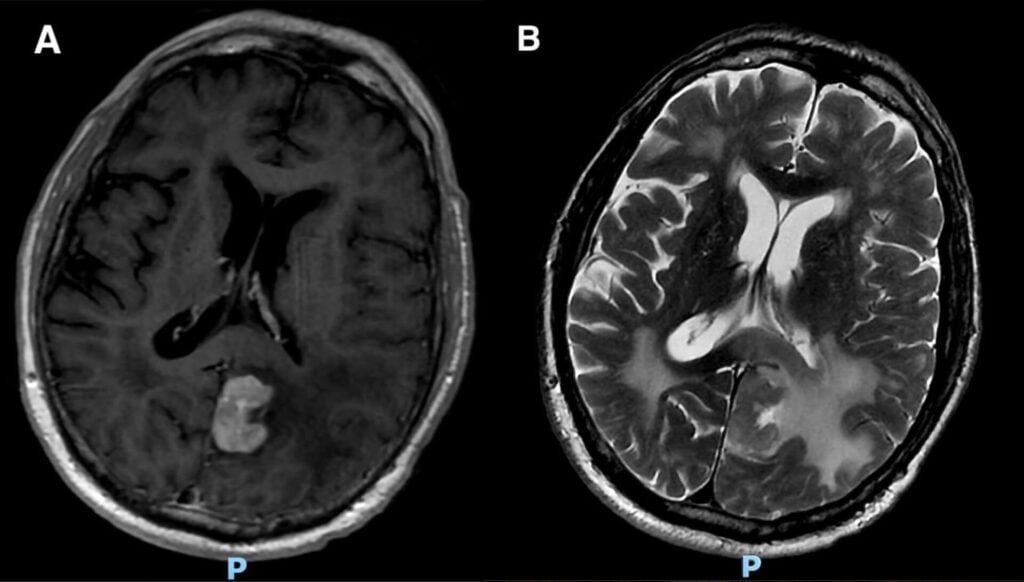

A 78-year-old male presented to the emergency department, noting difficulty with memory and simple tasks (i.e., interpreting a calendar or recalling what day/month it is) over the preceding 2-4 weeks. His past medical history was notable for prior malignant melanoma of the right shoulder s/p prior resection, squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) of the left tongue s/p resection, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, migraine, post-traumatic stress disorder, and a recent urinary tract infection. A number of laboratory studies were obtained, all of which returned normal or negative. Head CT was interpreted as normal. However, brain MRI with and without contrast demonstrated a 2.1 – 2.8 cm mass at the level of the left parieto-occipital lobe with significant surrounding edema (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Brain MRI axial T1 post-contrast sequence (A) and axial T2 propeller (B) demonstrating left parieto-occipital lobe lesion with surrounding vasogenic edema.

Consults to neurology, oncology, neurosurgery, and optometry were placed. A tentative differential for the lesion was entertained with concern for possible intracranial metastasis (stemming from prior cancers), primary central nervous system (CNS) neoplasm, or CNS lymphoma. The primary concern initially was that the lesion likely represented intracranial metastasis from the patient’s past melanoma. The patient was initiated on oral dexamethasone 4 mg BID in an effort to mitigate the impact of the lesion’s surrounding edema on nearby brain structures. After discussing various management options, the decision was ultimately made for neurosurgery to perform stereotactic brain biopsy. The patient’s brain biopsy returned with findings consistent with high-grade B-cell lymphoma.

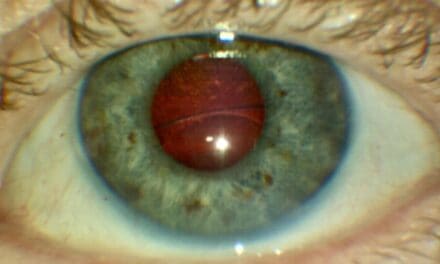

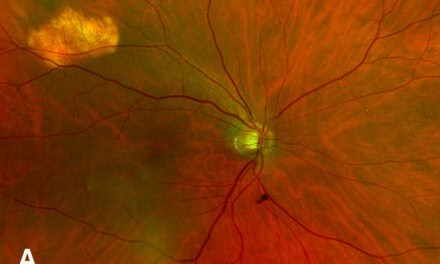

Optometry examination was performed on post-op day one following brain lesion biopsy. The patient was notably confused during the exam but was oriented to person (could identify self but not place or time during the visit). Visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye. Pupil and extraocular motility evaluation were normal. Color vision evaluation was attempted, but the patient was unable to perform this test due to confusion. Slit lamp examination, intraocular pressure, and dilated fundus examination were all within normal limits; there were optic disc abnormalities or retinal/choroidal lesions. Automated perimetry (Humphrey Visual Field 24-2) was performed and demonstrated a significant right homonymous hemianopia (Figure 2).

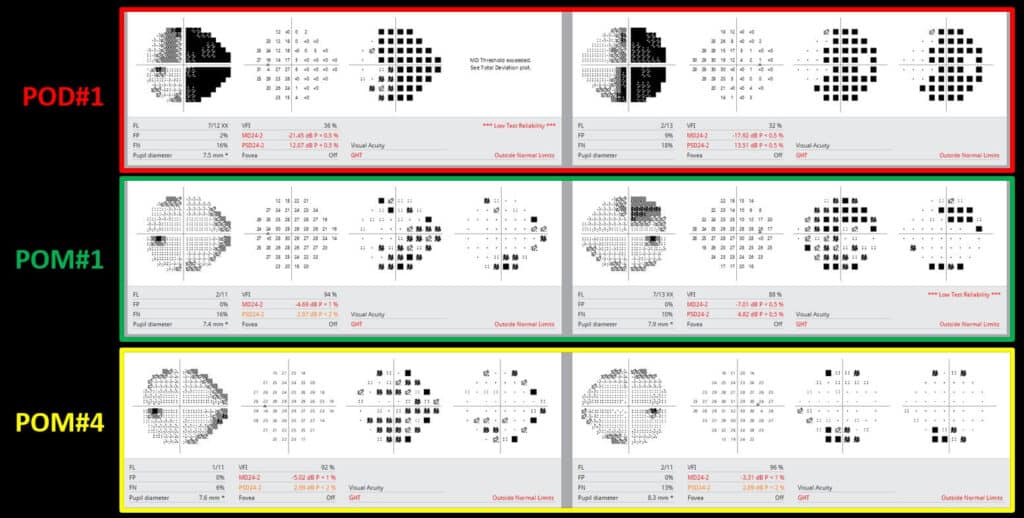

Figure 2. Serial Humphrey visual field (HVF) examinations on post-op day #1 (POD#1), and post-op months 1 and 4 (POM#1, POM#4).

The patient’s oncology team initiated high-dose methotrexate-based chemotherapy and continued systemic steroids. Management was later transitioned to ibrutinib, a Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitor chemotherapeutic agent. Systemic evaluation, including positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, demonstrated no findings that would indicate extracranial lymphomatous involvement (i.e. the patient’s disease seemed to be confined to the brain). The patient’s level of confusion improved to some degree. At follow-up eye exams 1-4 months after neurosurgical resection, the visual field testing demonstrated remarkable recovery of the patient’s right homonymous hemianopia (Figure 2).

Discussion

The patient in this case report demonstrates the possibility of individuals presenting with multiple systemic malignancies. The patient’s history of SCC of the left tongue and melanoma of the right shoulder certainly loomed large on the initial differential as to the primary site responsible for the intracranial lesion. However, this patient ended up being diagnosed with yet another systemic malignancy – CNS lymphoma.

Primary CNS lymphoma (PCNSL) is an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma that can impact the brain, spinal cord, eye, or cerebrospinal fluid (CSF).1,2 Clinical presentation varies widely depending on the predominant site of involvement, though the majority of cases present with brain parenchymal involvement.3 PCNSL patients may present with focal neurologic deficits (i.e. cranial nerve deficit, ataxia, etc) or non-specific signs or symptoms (i.e. headache, seizure, changes in mood or personality, etc).3

Though rare, PCNSL cases have been reported to be on the rise in recent years in older adults.1,2 Patients on long-term immunosuppressive medications (i.e. organ transplant recipients) are among those at highest risk for development of PCNSL.3 The fundamental nature of the immune system is altered in individuals who are immunocompromised, which can result in cellular derangements impacting B-cells, T-cells, microglia, and astroctyes.3

Patients who present with acute neurologic signs or symptoms should undergo prompt neuroimaging, and a brain MRI with and without contrast is the preferred modality for patients with PCNSL.4 Systemic evaluation to assess for lymphoma lesions at other locations in the body is also critical; PET/CT imaging can help identify sites of abnormal metabolic activity, which may be worrying for other lymphomatous lesions.4,5 Definitive diagnosis of PCNSL requires a tissue sample, which may be obtained directly by brain biopsy, CSF examination, or vitrectomy.4 Lymphoma cells are sensitive to corticosteroids, and a tissue sample is recommended either before steroid initiation or within 48 hours to maximize diagnostic yield.4 Various treatment options exist for PCNSL patients including methotrexate-based regimens, radiation, and other forms of chemotherapeutic agents.5 Treatment may be administered in a staged fashion: induction (induce partial or complete response) followed by consolidation (eliminate residual disease, maintain remission).4 Of course, these treatments are not always benign and carry neurotoxic side effects that may complicate the post-treatment recovery.4

There are case reports in the literature of patients with CNS lymphoma presenting with visual pathway deficits (i.e. homonymous hemianopia) and a variety of neuro-ophthalmic signs or symptoms.6-8 The patient in this report presented with confusion and visual deficits and was ultimately found to have a fairly dense right homonymous hemianopia. Fortunately, his visual deficits recovered to near resolution over a four-month timeframe. Potentially, the significant vasogenic edema at presentation was compressing visual pathway fibers, resulting in visual dysfunction. The chemotherapy regimen in concert with steroids helped to significantly decrease the size of the CNS lymphoma lesion and also the surrounding vasogenic edema, allowing for impressive visual recovery. Eye care providers must recognize the clinical heterogeneity for patients with PCNSL and keep this entity as a differential diagnosis in patients presenting with acute neurologic/neuro-ophthalmic dysfunction.

Clinical Pearls

- CNS lymphoma may present with clinical heterogeneity, and some patients present with neuro-ophthalmic signs or symptoms.

- Intracranial metastasis must be considered in patients with a history of cancer presenting with visual pathway deficits and neurologic symptoms. Tissue biopsy can help to solidify diagnosis.

- Vasogenic edema surrounding intracranial lesions may be amenable to surgical and/or medical intervention.

REFERENCES

- Lv C, Wang J, Zhou M, Xu JY, Chen B, Wan Y. Primary central nervous system lymphoma in the United States, 1975-2017. Ther Adv Hematol. 2022 Jan 23;13:20406207211066166. doi: 10.1177/20406207211066166. PMID: 35096360; PMCID: PMC8793121.

- Ohanyan S, Buxbaum C, Stein P, Ringelstein-Harlev S, Shelly S. Prognostic Impacts of Age, Diagnosis Time, and Relapses in Primary CNS Lymphoma. J Clin Med. 2024 Aug 13;13(16):4745. doi: 10.3390/jcm13164745. PMID: 39200887; PMCID: PMC11355736. open access.

- Ferreri AJM, Calimeri T, Cwynarski K, Dietrich J, Grommes C, Hoang-Xuan K, Hu LS, Illerhaus G, Nayak L, Ponzoni M, Batchelor TT. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2023 Jun 15;9(1):29. doi: 10.1038/s41572-023-00439-0. PMID: 37322012; PMCID: PMC10637780.

- Schaff LR, Grommes C. Primary central nervous system lymphoma. Blood. 2022 Sep 1;140(9):971-979. doi: 10.1182/blood.2020008377. PMID: 34699590; PMCID: PMC9437714.

- Hochberg FH, Baehring JM, Hochberg EP. Primary CNS lymphoma. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2007 Jan;3(1):24-35. doi: 10.1038/ncpneuro0395. PMID: 17205072.

- Chatterjee S, Angelov L, Ahluwalia MS, Yeaney GA. Epstein-Barr virus-associated primary central nervous system lymphoma in a patient with diffuse cutaneous systemic sclerosis on long-term mycophenolate mofetil. Joint Bone Spine. 2020 Mar;87(2):163-166. doi: 10.1016/j.jbspin.2019.10.005. Epub 2019 Oct 24. PMID: 31669807.

- Dermarkarian CR, Kini AT, Al Othman BA, Lee AG. Neuro-Ophthalmic Manifestations of Intracranial Malignancies. J Neuroophthalmol. 2020 Sep;40(3):e31-e48. doi: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000000950. PMID: 32282510.

- Ohe Y, Hayashi T, Mishima K, Nishikawa R, Sasaki A, Matsuda H, Uchino A, Tanahashi N. Central nervous system lymphoma initially diagnosed as tumefactive multiple sclerosis after brain biopsy. Intern Med. 2013;52(4):483-8. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.52.8531. Epub 2013 Feb 15. PMID: 23411706.

Dr. Kane graduated from New England College of Optometry in 2015 and went on to complete an ocular disease/primary care residency at VA Boston Jamaica Plain from 2015-2016. He is currently an attending optometrist at VA Boston. His interests include clinical teaching, neuro-ophthalmic disease, retinal vascular disease, glaucoma, and ocular manifestations of systemic disease.