Diagnosis and Management of Posterior Cortical Atrophy from an Eye Care Perspective

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) is a neurodegenerative condition presenting with visual symptoms secondary to posterior cortical dysfunction. PCA has been described as a variant of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), but other etiologies such as Lewy body disease have been implicated. The age of onset for PCA is typically between 50 and 65, while onset for AD is typically after 65. In early PCA, memory and other cognitive functions are relatively preserved, while visual symptoms are more pronounced. Consequently, patients commonly present initially to eye care professionals, seeking evaluation for what appear to be primary visual disturbances.

CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old white male presented with complaints of blurred vision for approximately two years. The patient also noted he had trouble seeing his dogs off to the sides when walking them. Confrontation fields were restricted in all quadrants and visual acuity mildly reduced. Ocular health was unremarkable. A subsequent neuropsychological evaluation suspected a diagnosis of the PCA variant of AD. Brain imaging confirmed the presence of posterior parietal and occipital cortical atrophy.

CONCLUSION

Patients with PCA can initially present with non-specific visuospatial and visuoperceptual complaints. Oftentimes, lack of ocular findings and minimal memory deficits makes an early diagnosis challenging. If suspected, a neuropsychological examination with structural or functional neuroimaging can confirm the presence of PCA. Treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors may be useful. Clinical features, diagnostic testing, and management of PCA from an eye care perspective will be discussed in this case report.

Keywords: posterior cortical atrophy, Alzheimer’s dementia, low vision, magnetic resonance imaging

INTRODUCTION

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease characterized by functional and visual processing dysfunction associated with atrophy of the parietal and occipital lobes of the brain. PCA has disease comorbidities with both Alzheimer’s disease (AD) and Lewy body disease (LBD) and should be considered in those patients as a differential.1 PCA often presents with complex visual cortical symptoms in the absence of ocular pathology. Brain neuroimaging such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or positron emission tomography (PET) can confirm the diagnosis.2 PCA poses unique diagnostic and therapeutic challenges, and often leads to misdiagnosis or diagnostic delays. This paper will explore clinical features and insight to assist clinicians with the early diagnosis and management of PCA.

CASE REPORT

A 64-year-old white male was referred by his primary care physician (PCP) for a routine eye exam with concerns of blur in each eye, with mild progression over approximately the past two years. Ocular history was remarkable for mild age-related cataracts. No history of oculomotor function was available. His medical history included hypertension. There was no active diagnosis of dementia; however, records from his PCP noted the patient had progressive forgetfulness over the past year. He was alert to person, place, and time, but mild memory deficits were apparent.

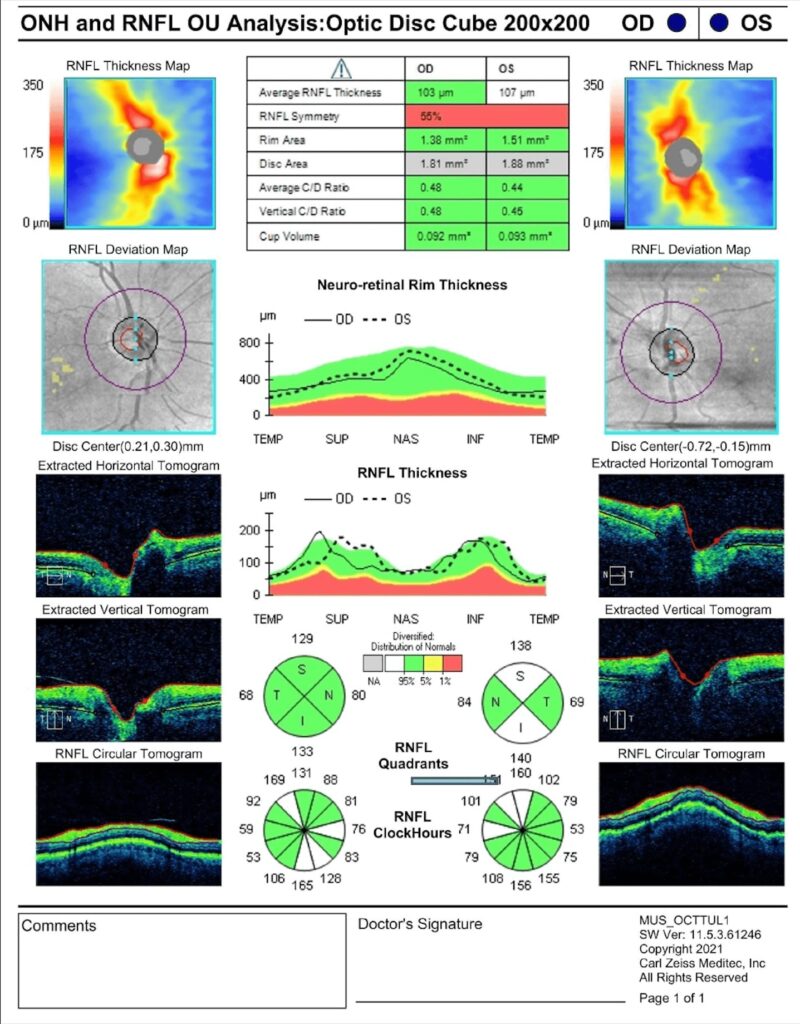

The best corrected visual acuity was 20/30 in the right and left eyes. Pupil assessment was unremarkable. Extraocular movements were grossly full, though the patient had difficulties following the target during testing. Confrontation fields were restricted in all quadrants in each eye: the patient stated he could not see any fingers during testing. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed mild age-related cataracts. A dilated fundus examination was overall unremarkable. No signs of optic nerve cupping, pallor, or swelling were noted. An optic nerve optical coherence tomography test showed no overt abnormalities (Figure 1).

At this point, the only finding to explain the blurred vision were the age-related cataracts, although due to their mild grading, a surgical consult was not yet recommended. No overt diagnosis explained the anomalous confrontation field findings. At that time, it was suspected the patient may have poorly understood the testing instructions. The patient had an upcoming brain MRI study ordered by his PCP to investigate the recent memory issues. Although formal visual field testing may have yielded additional context, it was not performed at this visit due to the patient appearing fatigued and in light of the upcoming MRI. It was presumed that the MRI would likely reveal more specific underlying pathology of any true field loss. The lack of acute symptoms such as those associated with a possible recent stroke and the stated chronicity of visual symptoms did not prompt the ordering of emergent neuroimaging. He was encouraged to follow through with the MRI as it could reveal a neurological cause of the vision loss.

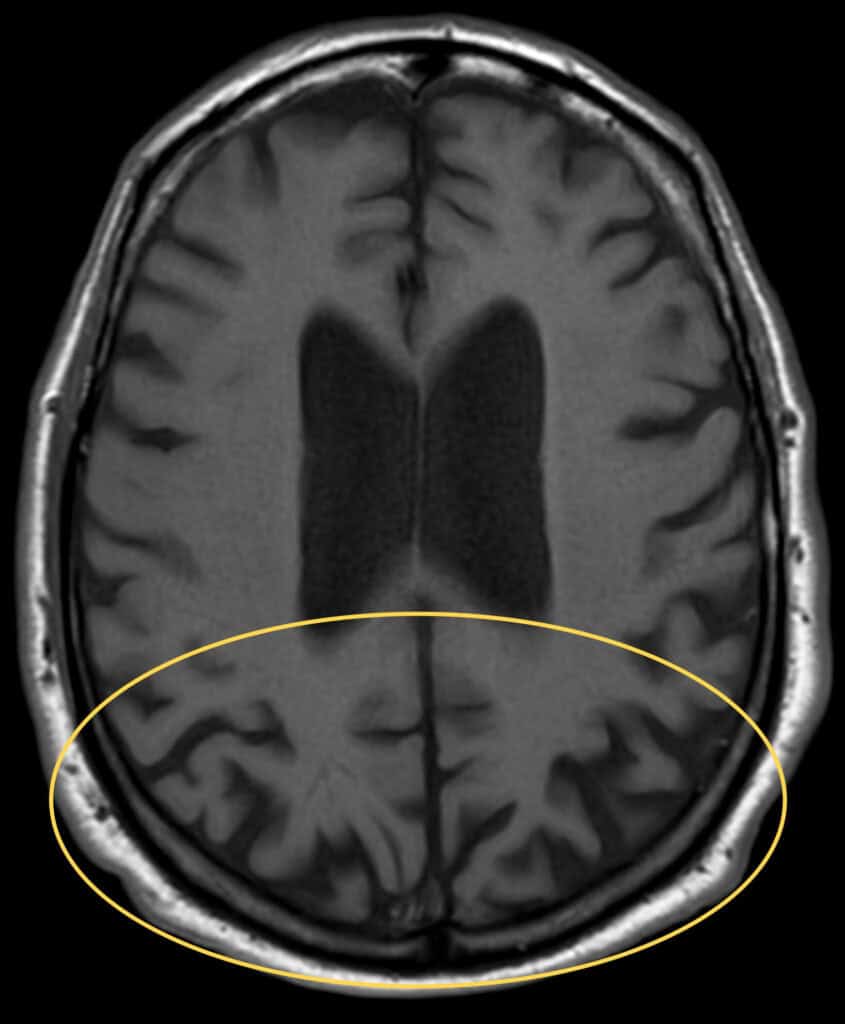

A neuropsychology evaluation was performed ten days after the initial encounter. The report stated the patient had stopped driving over two years prior due to “vision issues.” Given the age of onset and timeline of visual symptoms starting prior to memory loss, this evaluation suggested a diagnosis of PCA. The PCP later diagnosed Alzheimer’s disease, dementia, and prescribed memantine. It is speculated that the diagnosis of AD was made to address the memory loss for which the PCP was following the patient prior to available MRI findings. An MRI performed one month later showed central cortical atrophy, more prominently in the parietal and occipital lobes (Figure 2) and was otherwise unremarkable.

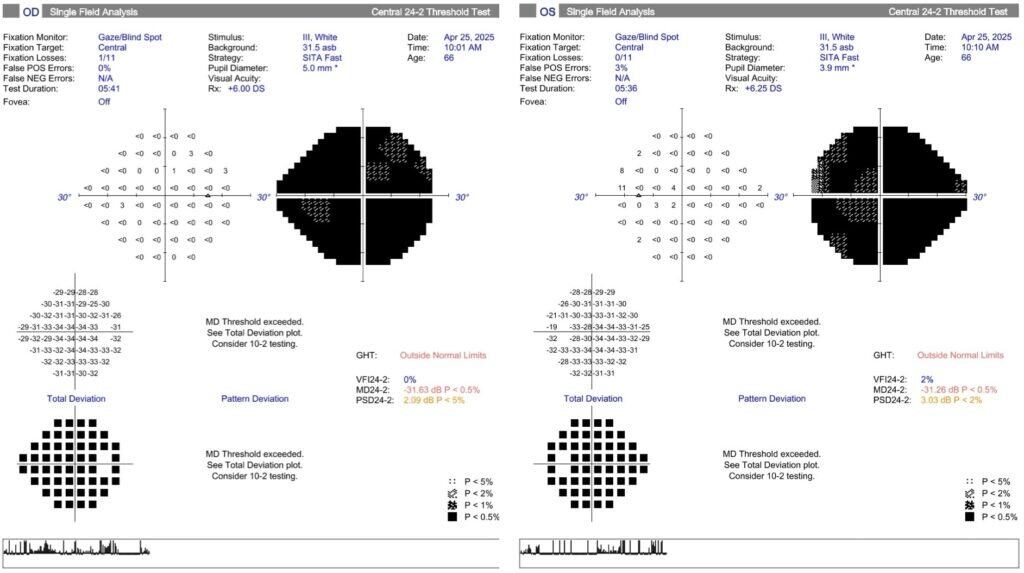

The patient returned to the eye clinic ten months later, with concerns of persistent blurred vision and difficulty seeing his dogs while walking them. His visual acuity, routine testing, and ocular examination remained stable compared to his initial visit. On further questioning, he shared that his wife now assisted him with tasks such as shaving and getting dressed due to his visual limitations. Although he remained mobile with the aid of a cane, he reported difficulty walking on uneven surfaces. He denied any issues recognizing familiar faces. According to his wife, the visual symptoms may have begun as early as seven years prior, when they first noticed that he was having difficulty navigating the road while driving. Humphrey visual field testing demonstrated diffuse bilateral field loss (Figure 3).

The nature and timeline of the patient’s visual impairment, together with the neuropsychology assessment and MRI findings, were consistent with a diagnosis of PCA. The patient was educated that he likely was experiencing a visual variant of Alzheimer’s disease and the various manifestations were reviewed in regard to vision. He was assured that his ocular health was normal and age appropriate. The patient was referred for a consultation with visual impairment services for mobility training and low vision device evaluation.

Figure 1. Retinal nerve fiber layer optical coherence tomography report shows robust and symmetric nerve tissue.

Figure 2. Transverse T1-weighted brain MRI image shows bilateral cortical thinning and sulcal widening in the bilateral occipital and posterior parietal regions (yellow oval).

Figure 3. 24-2 Humphrey Visual Field tests with a dense general diffuse vision loss bilaterally. Reliability is good in both eyes.

DISCUSSION

DISCUSSION

Posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), also known as Benson’s syndrome, is a rare neurodegenerative disease characterized by progressive cortical visual impairment caused by atrophy of the posterior cortex of the brain. A key feature is the disparity between posterior cortical dysfunction and the relative preservation of other cognitive domains. Basic visual processing problems, such as misplacement of items and difficulty reading and driving, are often among the first symptoms. Cognitive function, such as episodic memory and verbal communication, remains intact until later stages.4

While memory loss is not a prominent presenting feature, some level of impairment can occur concurrently in over half of PCA patients.4-6 In this case, visual symptoms preceded memory deficits by at least one year, and likely several years. The predominance of visual symptoms prior to memory complaints was a key diagnostic criterion noted in the patient’s neuropsychological evaluation and supported the clinical diagnosis of PCA.

There is a high comorbidity between PCA and Alzheimer’s disease (AD), however, one differentiator between the two is age of onset.7 The onset of PCA is typically seen between ages 50 and 65 with a mean onset of 58.9 as determined by Schott et al.4,8-10 Conversely, incidences of AD significantly increase after age 65.11 Another differentiator between AD and PCA is the progression of symptom onset. AD leads with episodic memory impairment, while PCA leads with earlier visual processing deficits.12 It’s often noticed that initially, patients with AD will have trouble with cognitive functions such as forgetting details and repeating questions, while patients with PCA have trouble with visuospatial activities such as reading and recognizing faces. Both diseases are confirmed with radiologic imaging. There is more pronounced atrophy in the medial temporal lobe for AD and more pronounced atrophy in the parietal occipital regions for PCA.13 However, PCA is often misdiagnosed as AD in later stages of PCA. This is because in later stages of PCA, patients may present with greater cognitive decline, and neuroimaging can show diffuse cortical atrophy with hippocampal involvement, resembling AD, so the initial occipito-parietal pattern may not stand out in the same way.14

Other than AD, PCA has been less-commonly linked to Lewy body disease (LBD), prion disease, and corticobasilar degeneration. LBD can present initially with similar visual disturbances as PCA, but are distinguished by visual hallucinations and parkinsonian symptoms.15 Prion disease has a rapid progression, with symptoms advancing within months, while PCA develops over years. Prion disease also presents with cerebral spinal fluid protein markers.16 Corticobasilar degeneration is distinguished by its “alien limb phenomenon” where one limb moves involuntarily, affecting the motor system prior to visual.17

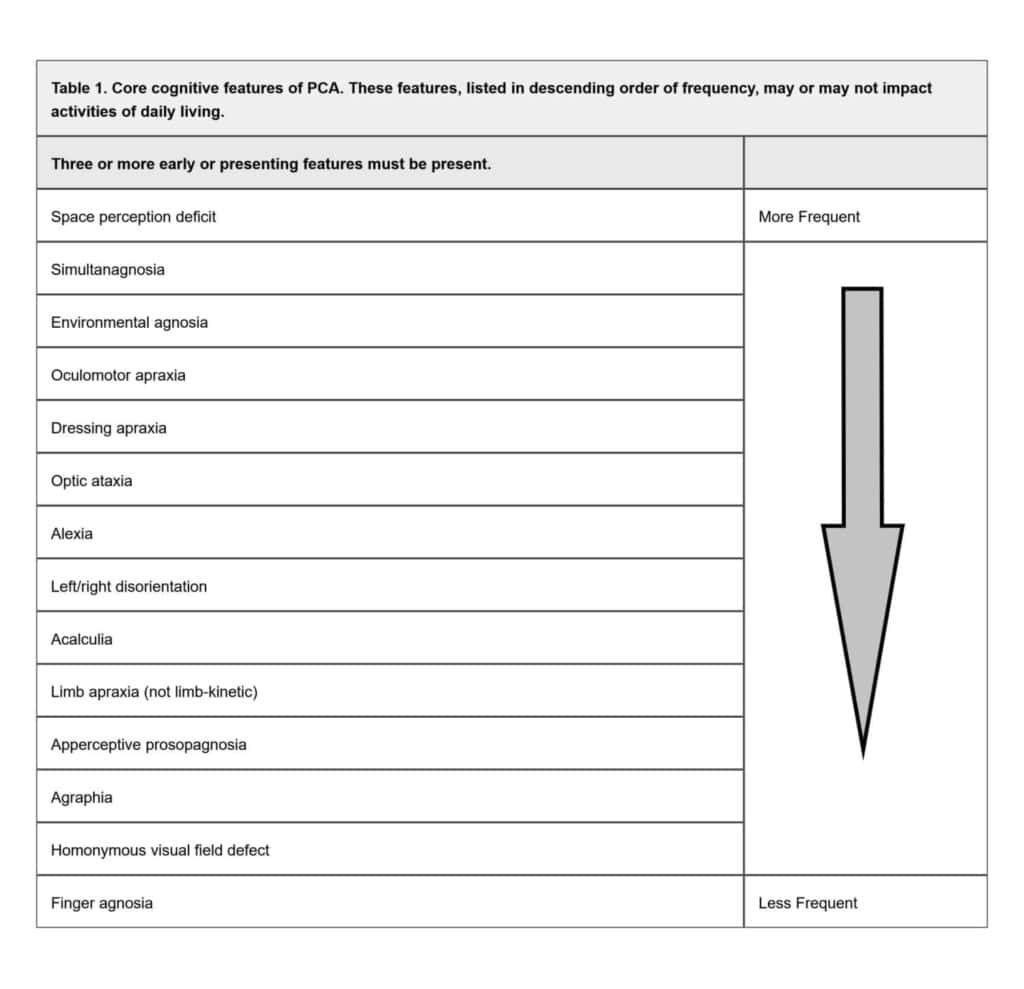

Diagnosis of PCA is based on clinical symptoms and signs, often supported with radiological imaging of the brain. An insidious onset and gradual progression of symptoms are principal characteristics of this condition. PCA should not be considered with evidence of brain mass lesions, vascular disease including focal stroke, or primary ocular disease sufficiently explaining the clinical impairment.3 A retrospective study by Shir et al. looked at 558 PCA patients and found the most common initial symptoms were object misplacement, reading problems, driving difficulties, and disorders of basic visual processing (i.e., blurred vision, color misperception, visual field defects, diplopia).4 The most prevalent presenting signs consisted of constructional apraxia, acalculia, simultanagnosia, space perception deficits, and alexia.4 Crutch et al. proposed a classification system which required the presence of at least three specific cognitive features for the diagnosis of PCA (see Table 1). It also requires relative functional sparing of anterograde memory, speech and nonvisual language, behavior and personality, and executive functions.3 The patient’s inability to see fingers during confrontation visual field testing could have indicated an underlying inability to perceive peripheral stimuli while fixating on a target, a feature of simultanagnosia.

A referral for a neuropsychological evaluation can provide objective evidence of cognitive dysfunction in domains affected by PCA and those typically conserved. Testing indicating deficiencies in object perception, space perception, calculation, and spelling, with preserved recognition memory may support this diagnosis. Alerting the clinician of the suspicion for PCA in the referral is useful, as the patient may need instructions given verbally as opposed to written material.18,19 In this case, the neuropsychology evaluation promptly diagnosed PCA prior to neuroimaging based on the history and cognitive testing alone.

The Repeatable Battery for the Assessment of Neuropsychological Status (RBANS) is a standardized cognitive assessment tool commonly employed in the diagnosis and monitoring of AD variants.20 It consists of five subtests evaluating various aspects of brain activity including memory and visuospatial/constructional skills through tasks such as geometric shape copying and pattern recognition. The patient’s RBANS assessment revealed deficiencies in both the visual and memory subtests, though, it was noted that his visual impairment and test-related anxiety likely exaggerated the apparent cognitive deficits, including memory. These results reinforced evidence of the patient’s visuospatial deficits, while deficiencies of other domains were less prominent.

There is no consensus on how to diagnose PCA, however, physicians rely on advanced neuroimaging to rule out other etiologies (e.g. stroke or tumor), along with the commonly found characteristics of PCA. Brain MRI can detect atrophy which predominantly affects the occipital, parietal, and posterior temporal lobes in PCA compared to the more diffuse cortical atrophy as observed in typical AD.2,3,18 Functional neuroimaging, such as single photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and fluorodeoxyglucose positron fludeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET), may depict hypoperfusion and hypometabolism, respectively, of the occipito-parietal cortices.18,21

Visual field testing in PCA patients often reveals homonymous single hemifield defects, and less commonly both hemifields. The left hemifield is affected more frequently, consistent with reports of predominant right visual cortex atrophy observed in PCA.22,23 Eye movement abnormalities, such as poor saccadic and pursuit performance, have been noted in PCA patients.24 This patient’s poor performance during extraocular muscle testing may have reflected a dysfunction with pursuit. There are no definitive blood labs for PCA, but it is common to order biomarkers for AD, such as amyloid-beta (Aβ) and plasma phosphorylated-tau (pTau), to assist in diagnosis.25

Multiple studies utilizing optical coherence tomography (OCT) have demonstrated retinal nerve fiber (RNFL) and inner retinal layer thinning in AD and other neurodegenerative conditions.26-28 RNFL thinning was not apparent in OCT imaging for this case (Figure 1). However, research examining OCT anomalies specific to PCA remains limited. Sun et al. identified retinal microvascular abnormalities, including enlarged foveal avascular zones, in small cohorts of PCA (n=12) and AD (n=19) patients using OCT angiography.27 While additional high-quality studies are warranted, OCT technology represents a promising, non-invasive diagnostic and monitoring tool for neurodegenerative diseases, including PCA.

There are currently no specific treatments for PCA, but the association with AD and LBD leads to management of the underlying pathophysiology with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors, such as donepezil, rivastigmine, and galantamine.1,29 Memantine, a glutamate receptor antagonist used for AD, has not yet been studied in PCA specifically, but case studies have shown benefits to cognition and activities of daily living in moderate to severe AD.29 Aducanumab, an Aβ targeting monoclonal antibody, is currently being investigated for its use in AD, including PCA, but its meaningful benefit to cognitive ability and function requires further study.19

Management for PCA is primarily supportive with low vision and occupational therapy referrals to help maximize function with day-to-day tasks.1 Depression and anxiety are common psychiatric symptoms associated with PCA. Patients with symptoms of depression and anxiety should be considered for antidepressants, specifically avoiding those with anticholinergic activities, which can worsen cognitive decline.29

VISION REHABILITATION CONSIDERATIONS

Individuals with PCA have a significantly different presentation and response to the low vision and blind rehabilitation therapy options as compared to other more common ocular diseases. The challenges they face are similar to other neurologic diseases, which frequently affect fine motor skills, memory, speech, auditory and linguistic comprehension, and other higher order processing.

PCA patients struggle to process complex visual input, which often manifests as simultanagnosia. Providing magnification aids, as commonly done with central vision loss, may further complicate their visual information processing. For instance, they may be able to identify individual letters but find themselves unable to identify the whole word. Furthermore, PCA patients often suffer from loss of fine motor skills, making steadying handheld magnifiers, scanning, and pressing buttons on digital devices daunting tasks.

Auditory feedback devices are often successfully implemented to assist patients with severe visual impairment in navigating their environment. Space perception deficits commonly associated with PCA may make these devices an attractive therapeutic solution. However, clinicians should note that auditory processing deficits are a possible comorbidity in PCA. Hardy et al. noted poor performance with auditory scene analysis tasks compared to patients with typical AD and healthy controls. This may cause difficulty hearing in busy environments secondary to temporal lobe dysfunction from PCA.20,21 Some auditory devices optometrists may prescribe include: OrCam, SeeingAI app, C-Pen reader, JAWS text-to-speech analyzer, and Audiobooks.

Prisms are often considered for patients with neurologic etiology visual field loss and neglect. However, there is much dispute as to their effectiveness in vision rehabilitation and overall benefit to the patient. While some studies show positive correlations with prism adaptation, others were less supportive.30-33 Visual field loss and neglect with PCA patients can often be difficult to test using standard automated perimetry. Clinicians in vision rehabilitation can demonstrate the prisms and assess patient responses through observing their gait, verbal feedback, and performance with other fine motor skills. It is important to keep in mind that prism adaptation is often unsuccessful for visual pathway diseases.24 Factors like duration and stage of disease, memory loss, depth and affected areas of visual field loss and neglect, patient’s refractive status, and age are likely to influence adaptation.

Orientation and mobility are highly likely to be affected by PCA. Crutch et al. described phenomena where static objects are perceived to have movement. The same study had also noted a patient reporting 180-degree upside-down reversal orientation of vision.1 Combined with more well-known PCA symptoms of simultanagnosia, visual field loss, alexia, left and right disorientation and executive dysfunction, patients are unlikely to be able to drive. They also noted that PCA patients have reported heightened sensitivity to glare and reflection enough to report pain and disruption of balance. It is hypothesized that PCA is linked to aberrant visuovestibular interactions.1 Tinted lenses for glare and a support cane or walker should be considered for affected patients.

CONCLUSION

Posterior cortical atrophy is characterized by dysfunction of the occipito-parietal cortices, leading to progressive visual and spatial deficits. Diagnosis can be challenging due to vague visual complaints and minimal ocular findings. Comorbidities common in elderly patients such as dry eye disease and cataracts may further complicate the underlying diagnosis. Familiarity with the early signs and symptoms, demographics, and the use of neuropsychological evaluation and brain imaging can support earlier recognition by eye care professionals. In this case, a neuropsychology referral was crucial for the timely recognition and diagnosis of PCA. Therefore, a multi-disciplinary team approach is often critical for the diagnosis and the management of this disease. While treatment options remain limited, referral for vision rehabilitation and collaboration with a low vision specialist can help optimize patients’ functional vision and quality of life.

REFERENCES

- Crutch SJ, Lehmann M, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, Rossor MN, Fox NC. Posterior cortical atrophy. Lancet Neurol. 2012 Feb;11(2):170–8.

- Whitwell JL, Jack CRJ, Kantarci K, Weigand SD, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, et al. Imaging correlates of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurobiol Aging. 2007 July;28(7):1051–61.

- Crutch SJ, Schott JM, Rabinovici GD, Murray M, Snowden JS, van der Flier WM, et al. Consensus classification of posterior cortical atrophy. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2017 Aug;13(8):870–84.

- Shir D, Lee N, McCarter SJ, Ramanan VK, Botha H, Knopman DS, et al. Longitudinal Evolution of Posterior Cortical Atrophy: Diagnostic Delays, Overlapping Phenotypes, and Clinical Outcomes. Neurology. 2025 May 13;104(9):e213559.

- Yerstein O, Parand L, Liang LJ, Isaac A, Mendez MF. Benson’s Disease or Posterior Cortical Atrophy, Revisited. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2021;82(2):493–502.

- Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Boeve BF, Knopman DS, Tang-Wai DF, Drubach DA, et al. Visual hallucinations in posterior cortical atrophy. Arch Neurol. 2006 Oct;63(10):1427–32.

- Suárez-González A, Lehmann M, Shakespeare TJ, Yong KXX, Paterson RW, Slattery CF, et al. Effect of age at onset on cortical thickness and cognition in posterior cortical atrophy. Neurobiol Aging. 2016 Aug;44:108–13.

- Reñé R, Muñoz S, Campdelacreu J, Gascon-Bayarri J, Rico I, Juncadella M, et al. Complex visual manifestations of posterior cortical atrophy. J Neuro-Ophthalmol Off J North Am Neuro-Ophthalmol Soc. 2012 Dec;32(4):307–12.

- Tang-Wai DF, Graff-Radford NR, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, Parisi JE, Crook R, et al. Clinical, genetic, and neuropathologic characteristics of posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology. 2004 Oct 12;63(7):1168–74.

- Schott JM, Crutch SJ, Carrasquillo MM, Uphill J, Shakespeare TJ, Ryan NS, et al. Genetic risk factors for the posterior cortical atrophy variant of Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2016 Aug;12(8):862–71.

- Qiu C, Kivipelto M, von Strauss E. Epidemiology of Alzheimer’s disease: occurrence, determinants, and strategies toward intervention. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2009;11(2):111–28.

- Maia da Silva MN, Millington RS, Bridge H, James-Galton M, Plant GT. Visual Dysfunction in Posterior Cortical Atrophy. Front Neurol. 2017;8:389.

- Jarholm JA, Bjørnerud A, Dalaker TO, Akhavi MS, Kirsebom BE, Pålhaugen L, et al. Medial Temporal Lobe Atrophy in Predementia Alzheimer’s Disease: A Longitudinal Multi-Site Study Comparing Staging and A/T/N in a Clinical Research Cohort. J Alzheimers Dis JAD. 2023;94(1):259–79.

- Sabuncu MR, Desikan RS, Sepulcre J, Yeo BTT, Liu H, Schmansky NJ, et al. The dynamics of cortical and hippocampal atrophy in Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2011 Aug;68(8):1040–8.

- Metzler-Baddeley C, Baddeley RJ, Lovell PG, Laffan A, Jones RW. Visual impairments in dementia with Lewy bodies and posterior cortical atrophy. Neuropsychology. 2010 Jan;24(1):35–48.

- Depaz R, Haik S, Peoc’h K, Seilhean D, Grabli D, Vicart S, et al. Long-standing Prion Dementia Manifesting as Posterior Cortical Atrophy. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord [Internet]. 2012;26(3). Available from: https://journals.lww.com/alzheimerjournal/fulltext/2012/07000/long_standing_prion_dementia_manifesting_as.16.aspx

- Lewis-Smith DJ, Wolpe N, Ghosh BCP, Rowe JB. Alien limb in the corticobasal syndrome: phenomenological characteristics and relationship to apraxia. J Neurol. 2020 Apr;267(4):1147–57.

- Schott JM, Crutch SJ. Posterior Cortical Atrophy. Contin Minneap Minn. 2019 Feb;25(1):52–75.

- Lehmann M, Crutch SJ, Ridgway GR, Ridha BH, Barnes J, Warrington EK, et al. Cortical thickness and voxel-based morphometry in posterior cortical atrophy and typical Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2011 Aug;32(8):1466–76.

- Euler MJ, Duff K, King JB, Hoffman JM. Recall and recognition subtests of the repeatable battery for the assessment of neuropsychological status and their relationship to biomarkers of Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychol Dev Cogn B Aging Neuropsychol Cogn. 2023 Nov;30(6):885–902.

- Gardini S, Concari L, Pagliara S, Ghetti C, Venneri A, Caffarra P. Visuo-spatial imagery impairment in posterior cortical atrophy: a cognitive and SPECT study. Behav Neurol. 2011;24(2):123–32.

- Pelak VS, Smyth SF, Boyer PJ, Filley CM. Computerized visual field defects in posterior cortical atrophy. Neurology. 2011 Dec 13;77(24):2119–22.

- Millington RS, James-Galton M, Maia Da Silva MN, Plant GT, Bridge H. Lateralized occipital degeneration in posterior cortical atrophy predicts visual field deficits. NeuroImage Clin. 2017;14:242–9.

- Shakespeare TJ, Kaski D, Yong KXX, Paterson RW, Slattery CF, Ryan NS, et al. Abnormalities of fixation, saccade and pursuit in posterior cortical atrophy. Brain J Neurol. 2015 July;138(Pt 7):1976–91.

- DeMarco ML, Algeciras-Schimnich A, Budelier MM. Blood tests for Alzheimer’s disease: The impact of disease prevalence on test performance. Alzheimers Dement J Alzheimers Assoc. 2024 May;20(5):3661–3.

- Coppola G, Di Renzo A, Ziccardi L, Martelli F, Fadda A, Manni G, et al. Optical Coherence Tomography in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Meta-Analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(8):e0134750.

- Sun Y, Zhang L, Ye H, Leng L, Chen Y, Su Y, et al. Potential ocular indicators to distinguish posterior cortical atrophy and typical Alzheimer’s disease: a cross-section study using optical coherence tomography angiography. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2024 Mar 25;16(1):64.

- Cunha LP, Pires LA, Cruzeiro MM, Almeida ALM, Martins LC, Martins PN, et al. Optical coherence tomography in neurodegenerative disorders. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 2022 Feb;80(2):180–91.

- Yong KXX, Graff-Radford J, Ahmed S, Chapleau M, Ossenkoppele R, Putcha D, et al. Diagnosis and Management of Posterior Cortical Atrophy. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2023 Feb 1;25(2):23–43.

- Umeonwuka CI, Roos ,Ronel, and Ntsiea V. Clinical and demographic predictors of unilateral spatial neglect recovery after prism therapy among stroke survivors in the sub-acute phase of recovery. Neuropsychol Rehabil. 2023 Nov 26;33(10):1624–49.

- Mizuno K, Tsuji T, Takebayashi T, Fujiwara T, Hase K, Liu M. Prism adaptation therapy enhances rehabilitation of stroke patients with unilateral spatial neglect: a randomized, controlled trial. Neurorehabil Neural Repair. 2011 Oct;25(8):711–20.

- Qiu H, Wang J, Yi W, Yin Z, Wang H, Li J. Effects of Prism Adaptation on Unilateral Neglect After Stroke: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Am J Phys Med Rehabil [Internet]. 2021;100(3). Available from: https://journals.lww.com/ajpmr/fulltext/2021/03000/effects_of_prism_adaptation_on_unilateral_neglect.10.aspx

- Li J, Li L, Yang Y, Chen S. Effects of Prism Adaptation for Unilateral Spatial Neglect After Stroke: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am J Phys Med Rehabil [Internet]. 2021;100(6). Available from: https://journals.lww.com/ajpmr/fulltext/2021/06000/effects_of_prism_adaptation_for_unilateral_spatial.10.aspx