Photo Essay: Sclerochoroidal Calcifications

ABSTRACT

Sclerochoroidal calcifications (SCC) occur when calcium depositions within the sclera cause yellow placoid-like lesions, typically within the midperipheral superior temporal retina.1 The calcifications cause overlying choroidal and retinal pigment epithelium atrophy.1-2 Although most cases are idiopathic, SCC could be related to other systemic conditions.1-3

Keywords: Sclerochoroidal calcification

CASE REPORT

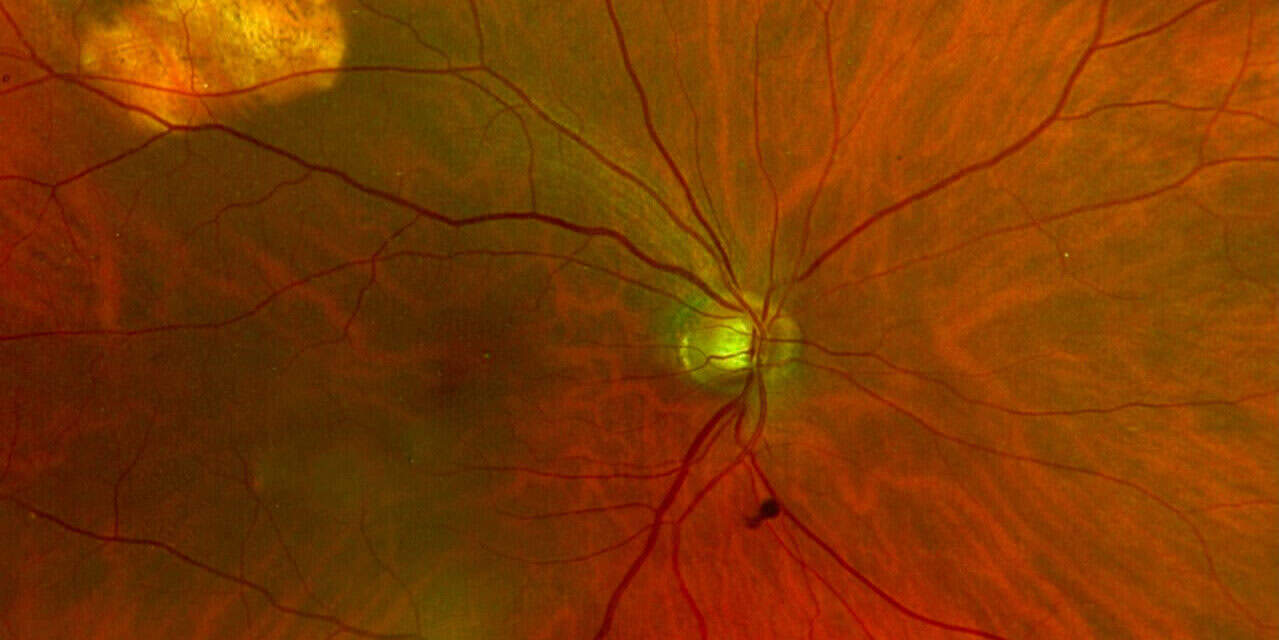

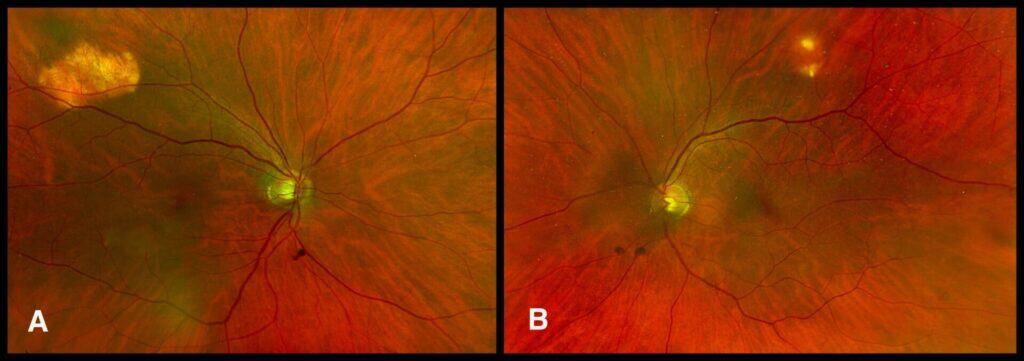

An 81-year-old Caucasian male presented for a routine eye exam with no visual complaints. He denied any changes in vision, ocular pain, flashes, or floaters. His ocular history was significant for moderate age-related cataracts in both eyes and a mild epiretinal membrane in his left eye. His entering visual acuity with correction was 20/25-2 in the right eye and 20/50+2 in the left eye at distance. The medical history was significant for hypertension and hearing loss. Confrontation visual fields, pupillary responses, and extraocular motility were normal. Slit lamp examination was unremarkable in both eyes. Upon dilation, grade 2+ nuclear sclerosis with trace cortical vacuoles was noted in both lenses. Posterior vitreous detachments were present in both eyes. Evaluation of the fundus revealed elevated, amelanotic lesions measuring approximately 3 DD horizontally by 2 DD vertically along the superior temporal arcade in the right eye, and a similar amelanotic lesion measuring approximately 1 DD round along the superior temporal arcade in the left eye. The optic nerve heads were well perfused with well-defined margins and had a cup to disc ratio of 0.55 round in the right eye and 0.40 round in the left eye. The retinal vessels were of normal caliber in both eyes. The macula was flat with even pigment in the right eye and there was a mild epiretinal membrane present in the left eye. The peripheral retina was flat and intact for 360 degrees in both eyes. Given the elevation, location, and appearance of the lesions in both eyes, sclerochoroidal calcifications were suspected. Because these findings had not been documented in prior examinations, the patient was referred to a retina specialist for further evaluation to rule out malignancy.

At the retina specialist visit, optical coherence tomography (OCT) revealed elevation of each lesion without subretinal fluid. B-scan ultrasonography demonstrated hyperechoic lesions with shadowing bilaterally, consistent with calcification. The lesions were confirmed to be sclerochoroidal calcifications. Laboratory testing for serum and urine calcium, phosphorus, magnesium, and parathyroid hormone was recommended to rule out underlying systemic disease.

Figure 1. Posterior fundus photographs demonstrating elevated, amelanotic lesions along the superior temporal arcade in right eye (A) and left eye (B).

DISCUSSION

Sclerochoroidal calcifications are benign choroidal lesions of calcific deposition occurring at the oblique extraocular muscle insertion.3,4 They are uncommon and most often detected incidentally on routine examination in elderly Caucasians.1,3-5 A systematic literature review comprising 477 eyes from 300 patients reported the findings of diagnosis at a mean age of 68.4 years, with a slight female predilection (56%).6 The calcific lesions may occur unilaterally or bilaterally, with a marginally higher frequency of bilateral involvement (59%).6 Lesions may present in unifocal or multifocal distribution; however, multifocal lesions are more frequently observed (30.8%) than unifocal lesions (21.8%).6 They typically do not require treatment and pose little risk for subsequent vision loss or choroidal neovascular membrane (CNVM).1,5 A large review of 161 patients, Gunduz and Tetik revealed that 93% of patients remained stable, 5% developed a CNVM, and 2% exhibited increased atrophy or lesion enlargement. Likewise, a retrospective study by Shields et al found no cases of CNVM in 179 eyes after four years of follow-up.

Various imaging modalities aid in the identification of SCCs. Fundus autofluorescence demonstrates hyperfluorescence in calcified regions and hypofluorescence in areas of RPE atrophy.6 Fluorescein angiography (FA) typically reveals hypofluorescence in the early phases, followed by hyperfluorescence and late staining. Indocyanine green angiography shows persistent hypocyanescence across all phases.3 Ocular ultrasonography characteristically identifies echo-dense placoid lesions at the scleral-choroidal interface with associated orbital shadowing.3 Enhanced depth imaging OCT can pinpoint calcium-containing plaques, with one study describing a “rocky or rolling” appearance within the sclera.2-3 Optical coherence tomography angiography displays decreased blood flow due to masking of the underlying choriocapillaris.6

The differential diagnosis for SCC includes choroidal metastasis, melanoma, osteoma, and lymphoma.1-3 Metastatic lesions are typically dome-shaped, associated with overlying serous retinal detachments, and most often occur in patients with a known history of systemic cancer.7 On ultrasonography, choroidal melanoma generally demonstrates low to medium internal reflectivity with evidence of vascularity on FA.7 Choroidal osteoma is characterized by a juxtapapillary location and a distinctive FA pattern showing early patchy hyperfluorescence with late staining from spider vessels.7 Lastly, choroidal lymphoma typically presents with vision changes, demonstrates low to medium internal reflectivity on ultrasonography, and may be associated with systemic lymphoma.8

Most cases of SCC are idiopathic; however, a positive correlation between younger age, bilaterality, and multifocal lesions with systemic associations has been reported.3,4,6 In these cases, SCC may be related to either dystrophic or metastatic calcifications.3,6 Dystrophic calcifications develop in necrotic or damaged tissues despite normal serum calcium and phosphorus levels.3,6 Tissue damage leads to increased plasma membrane permeability, disrupted ion transport, mineral deposition within mitochondria, and extracellular calcium accumulation.9,10 Other ocular examples include corneal band keratopathy, optic nerve head drusen, and calcification related to retinoblastomas.6 Conversely, metastatic calcification results from abnormal calcium and phosphorus metabolism, leading to deposition in otherwise healthy tissue.6 Common metabolic disorders that led to electrolyte imbalances are hyperparathyroidism, vitamin D intoxication, and renal disorders.3,6

All patients with SCC should undergo baseline blood and urine testing to rule out systemic complications. In a chart review of 179 patients, Shields et al. found that 27% of those with secondary SCC had hyperparathyroidism, with 15% of those cases linked to parathyroid adenoma. The study also identified associations with renal tubular disorders such as acquired Gitelman syndrome (11%) and Barter syndrome (2%). Recommended testing includes blood and urine calcium, phosphorus, potassium, magnesium levels, serum parathyroid hormone, and calcitonin.1,3 It is also important to recognize that patients taking diuretics could be at an increased risk for electrolyte imbalances.1,3 Due to the benign nature and limited risk for subsequent vision loss, routine ophthalmic monitoring is recommended for patients with SCC.

REFERENCES

- Shields, C. L., Hasanreisoglu, M., Saktanasate, J., Shields, P. W., Seibel, I., & Shields, J. A. (2015). Sclerochoroidal calcification. Retina, 35(3), 547–554.

- Fung, A. T., Arias, J. D., Shields, C. L., & Shields, J. A. (2013). SCLEROCHOROIDAL calcification is primarily a scleral condition based on enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography. JAMA Ophthalmology, 131(7), 960.

- Honavar, S. G. (2001). Sclerochoroidal calcification. Archives of Ophthalmology, 119(6), 833.

- Leys A, Stalmans P, Blanckaert J. Sclerochoroidal Calcification With Choroidal Neovascularization. Arch Ophthalmol. 2000;118(6):854–857.

- Gündüz, A. K., & Tetik, D. (2023). Diagnosis and management strategies in SCLEROCHOROIDAL calcification: A systematic review. Clinical Ophthalmology, Volume 17, 2665–2686.

- Mansour, AhmadM., Alameddine, RamziM., & Kahtani, E. (2014). Review of choroidal osteomas. Middle East African Journal of Ophthalmology, 21(3), 244.

- Shields, C. L., Arepalli, S., Pellegrini, M., Mashayekhi, A., & Shields, J. A. (2014). Choroidal lymphoma shows calm, rippled, or undulating topography on enhanced depth imaging optical coherence tomography in 14 eyes. Retina, 34(7), 1347–1353.

- Cooke, C. A. (2003). Idiopathic sclerochoroidal calcification. British Journal of Ophthalmology, 87(2), 245–246.

- Proudfoot, D. (2019). Calcium signaling and tissue calcification. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology, 11(10).

- Duvvuri, B., & Lood, C. (2021). Mitochondrial calcification. Immunometabolism, 3(1).