Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic Neuropathy: An Update On Ophthalmoplegic Migraine

INTRODUCTION

Recurrent painful ophthalmoplegic neuropathy (RPON) is a rare condition characterized by recurrent episodes of headache accompanied by ipsilateral paresis of one or more ocular motor cranial nerves.1,2 The condition was previously known as ophthalmoplegic migraine until its reclassification by the International Headache Society (IHS) in 2018.2 What is now RPON was initially reported in the 1860s by Gubler who shared the case of a patient with recurrent migraine-like headaches associated with oculomotor nerve paresis.3 A few decades later, the condition was again reported and, for the first time, given the name ophthalmoplegic migraine.4 The name aptly described what appeared to be a subtype of migraine that, instead of presenting with classic migraine aura symptoms, presented with ophthalmoplegia.

Almost since its inception, the debate over what exactly defines ophthalmoplegic migraine has been ongoing with an early peak in discourse in the mid-1900s.5–7 In the absence of any other potential causes for ophthalmoplegia, it seemed logical to conclude that in cases of migraine with ophthalmoplegia, the cause of ophthalmoplegia was the migraine mechanism itself. Subsequently, in 1988 when the IHS released their first International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD), ophthalmoplegic migraine was listed as a subtype of migraine.8 This publication also established diagnostic criteria for the first time to clarify a condition that had previously been loosely defined. The literature at the time on ophthalmoplegic migraine was muddled by cases with inconsistent symptoms or cases that did not thoroughly investigate other potential causes.7

Thankfully, the advent of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has provided more information about this unusual condition. Focal enhancements of cranial nerves paralyzed in ophthalmoplegic migraine were identified in some cases suggesting an inflammatory cause. Subsequently, in the next publication of the ICHD in 2004 ophthalmoplegic migraine was moved from a subtype of migraine to a type of cranial neuralgia that presents with migrainous headaches. Most recently, the latest ICHD publication in 2018 moved ophthalmoplegic migraine further away from its association with migraine and officially changed its name to RPON with the IHS stating the term ophthalmoplegic migraine is “old and inappropriate.2

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND CLINICAL FEATURES

From modern literature reviews of published cases, it seems that RPON typically presents in childhood with an average age of onset between 8 and 22 years.9,10 However, the reported age of initial onset varied from 3 months to 74 years.10 RPON appears slightly more common in the female population and does not seem more common within a particular race or ethnicity.9–11

Beyond the ICHD definition, the specific clinical features of RPON are poorly established and hindered by unreliable levels of detail in reported cases. Liu et al. published the largest review of RPON cases in 2020, which included 165 total patients. They found that 54% of cases involved the third cranial nerve, the most common nerve affected, followed by the sixth and fourth cranial nerves. Only 4% of cases involved multiple cranial nerves. In 94% of cases that included headache descriptive factors, the accompanying headache was migraine-like with nausea, photophobia, and/or phonophobia. In 97% of cases, diplopia symptoms started immediately or within one week of headache onset.10 Other major reviews cite higher rates of third cranial nerve involvement and lower rates of migraine-like features to the headache but are consistent with the time of onset.9,11 The headache symptoms typically resolve first and within a week of onset. The ophthalmoplegia lasts several weeks to a few months and might become persistent in cases with recurrent episodes.9–12 A smaller study reported after the initial episode recurrences occurred between 0.5-6 times per year, but the frequency might increase or decrease in subsequent years.13

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

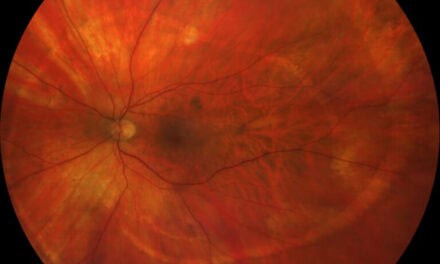

The exact cause of RPON is unknown and is further confounded by its inconsistent definition and rarity which make it difficult to study. Since it often presents with a migraine-like headache, it was initially thought to have a similar pathogenesis and was attributed to migrainous vasodilation compressing nearby ocular motor nerves, such as the internal carotid artery within the cavernous sinus.7 The suggested mechanism changed when a study of RPON cases involving third nerve palsies revealed most patients did not have pupillary abnormalities consistent with external compression of the nerve. It was then proposed that migraine-associated vasodilation instead caused downstream microvascular ischemia within the affected cranial nerves.14 Most recently, the advent of MRI demonstrated focal enhancement or enlargement of affected nerves in some cases of RPON, suggesting possible inflammatory or demyelinating causes. In this scenario, it is postulated the headache develops from co-aggravation to nearby trigeminal nerves.15

However, MRI results are oftentimes normal in RPON patients, and this finding begs the question of whether clinicians would benefit from RPON being further classified into different subtypes based on the varying clinical presentation of neuroimaging. In the Liu et al. case series, only 28% of cases had MRI findings which showed thickening or enhancement along the affected cranial nerve.10 Other reviews reported rates as high as 75%.9,11 Interestingly, in a 2009 case series of only adult-onset cases of ophthalmoplegia with migraine, the MRI results always appeared normal. These adult-onset cases were all patients with a prior diagnosis of migraine and had ophthalmoplegia that started within 24 hours of migraine onset. In addition to the strict temporal cutoff for ophthalmoplegia symptoms to start, they included cases who had not yet had a recurrent episode and, therefore, had not entirely met the now-established criteria for RPON.16 The fact that MRI findings are inconsistent in various studies may suggest that a different, non-inflammatory mechanism may be responsible for the condition when presenting in adulthood.

The various clinical presentations of what was once ophthalmoplegic migraine and is now established as RPON leads one to suspect it may, in fact, describe two or more conditions yet to be fully defined. Arguments have been made to reclassify the condition into a primary condition that is a subset of migraine and does not demonstrate inflammation on MRI and a secondary condition that is a true cranial neuropathy that demonstrates changes on neuroimaging and likely has some unknown cause that has not yet been detected.12,17,18

DIAGNOSIS

A careful clinical evaluation is necessary to diagnose RPON as it is a diagnosis of exclusion.2 An eye care provider can confirm the patient is experiencing true binocular diplopia, determine which specific oculomotor nerve(s) are affected, and accurately measure ocular deviation to best monitor for resolution. Additionally, an exam should note changes in visual field, pupil size, lid positioning, and optic nerve appearance, which can help guide the focus of neuroimaging when evaluating for differential diagnoses.

There are a few emergent differential diagnoses to consider. Neuroimaging is necessary to evaluate for cerebrovascular accident and space-occupying lesions along the pathways of the affected cranial nerves. Accompanying laboratory examination of blood and/or cerebrospinal fluid can assist in detecting infectious or inflammatory causes of ophthalmoplegia as guided by the case history. In those of the appropriate age, giant cell arteritis would be another emergent condition that can occasionally cause diplopia alongside headache.19 Other less emergent differential diagnoses include diabetic microvascular ischemia, demyelinating disease, elevated intracranial hypertension, and Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome. Tolosa-Hunt Syndrome can especially mimic RPON. The condition causes granulomatous inflammation in the cavernous sinus or orbital apex, resulting in a paresis of cranial nerve III, IV, or VI and ipsilateral periorbital headache. However, this syndrome was recently redefined by the IHS to require visualization of granulomas on MRI or detection of granulomas via biopsy for diagnosis. Neuroimaging without the presence of granulomas will eliminate this as a diagnosis.20

Since repeat episodes are necessary to diagnose RPON, it is impossible to diagnose this condition after the first reported episode. If all testing for differential diagnoses comes back normal and RPON is suspected, it is important to consider repeat neuroimaging or lab work periodically to evaluate for causes that might have been missed on initial testing. When the condition recurs, then the diagnosis of RPON can officially be made.

MANAGEMENT

Management of RPON involves resolving both the headache and the ophthalmoplegia. There is no established treatment protocol. Treatment is based on symptom severity, symptom duration, and the patient’s health history, such as if they have a previous diagnosis of migraine or if they have responded well to a specific treatment during a previous RPON episode. The headache symptoms may be managed with the patient’s typical migraine medicine or other headache management strategies for non-migrainous headaches. The eye care provider plays an important role in improving the patient’s quality of life by treating their diplopia symptoms. These symptoms can be managed with Fresnel prism or a temporary eye patch until they resolve.

The identification of inflammatory lesions on MRI has resulted in several RPON patients being treated with corticosteroids, which appeared to expedite the recovery process of ophthalmoplegia and some cases of persistent headaches.10–12 In cases where steroids have been ineffective, indomethacin, pregabalin, furosemide, and ergotamines have been utilized.11,12 One interesting RPON case with steroid-resistant ophthalmoplegia resolved rapidly after the use of 0.25% timolol maleate, initially prescribed to manage steroid-induced glaucoma. It is hypothesized this treatment managed the ophthalmoplegia through a similar pathway as to how beta blockers manage migraine.21 There is limited evidence for RPON prophylaxis despite it being a recurrent condition. There have been individual case reports of lamotrigine and pregabalin successfully used prophylactically.22,23 Ultimately, the rarity and self-resolving nature of RPON has made it difficult to study treatment effects and thus there is no current standard for treatment.

In cases that do not resolve completely, prism glasses, botulinum toxin injections, or strabismus surgery might be required to manage residual diplopia. In non-resolving cases, repeat neuroimaging is recommended to determine if a different cause is now detectable. The cranial nerve enhancement and thickening observed in some cases of RPON should diminish after each episode, though it may take several months or years to return to normal. Any changes that persist or enlarge should be looked at with suspicion. 9,12,24 For instance, there have been cases originally diagnosed as RPON but later determined to be schwannoma.24–26 Finally, there is emerging evidence that individuals with ophthalmoplegic migraine or RPON have an increased likelihood of glaucoma and perhaps a greater glaucoma risk than those with typical migraine. Specific attention should be paid to glaucoma development during their annual eye examination.27

CONCLUSION

As providers continue to report cases of RPON in the literature, the understanding of this rare condition should improve. Practitioners have already benefited from the ICHD’s updated definition in 2018, but this definition for RPON may encompass multiple conditions with different pathophysiologies that still need to be distinguished. As the academic knowledge of RPON evolves, the eye care provider’s technical skill in determining which cranial nerves are affected and prescribing options to control diplopia symptoms will always be a central aspect of RPON treatment. Additionally, documenting recurrences and ordering repeat neuroimaging as part of a multidisciplinary healthcare team will be critical in the continued best management of these patients.

REFERENCES

- Hansen SL, Borelli-Møller L, Strange P, Nielsen BM, Olesen J. Ophthalmoplegic migraine: diagnostic criteria, incidence of hospitalization and possible etiology. Acta Neurol Scand. 2009;81(1):54-60. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0404.1990.tb00931.x

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 2018;38(1):1-211. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202

- Gubler A. Paralysie de la troisieme paire droite, recidivant pour la troisieme fois. Gazette des Hospitaux Civil et Militaires. 1860;33:65-66.

- Charcot J. Sur un cas de migraine ophtalmoplégique (paralysie oculo-motrice periodique). Progr Med (Paris). 1890;31:83-86.

- Alpers BJ, Yaskin HE. Pathogenesis of ophthalmoplegic migraine. Archives of Ophthalmology. 1951;45(5):555-566. doi:10.1001/archopht.1951.01700010567008

- Friedman AP, Harter DH, Merritt HH. Ophthalmoplegic Migraine. Arch Neurol. 1962;7(4):320-327. doi:10.1001/archneur.1962.04210040072007

- Walsh JP, O’Doherty DS. A possible explanation of the mechanism of ophthalmoplegic migraine. Neurology. 1960;10(12):1079-1079. doi:10.1212/WNL.10.12.1079

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias and facial pain. Cephalalgia. 1988;8(7):1-96.

- Gelfand AA, Gelfand JM, Prabakhar P, Goadsby PJ. Ophthalmoplegic “Migraine” or Recurrent Ophthalmoplegic Cranial Neuropathy. J Child Neurol. 2012;27(6):759-766. doi:10.1177/0883073811426502

- Liu Y, Wang M, Bian X, et al. Proposed modified diagnostic criteria for recurrent painful ophthalmoplegic neuropathy: Five case reports and literature review. Cephalalgia. 2020;40(14):1657-1670. doi:10.1177/0333102420944872

- Furia A, Liguori R, Donadio V. Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic Neuropathy: A case report with atypical features and a review of the literature. Cephalalgia. 2023;43(1):033310242211333. doi:10.1177/03331024221133386

- Smith S V., Schuster NM. Relapsing Painful Ophthalmoplegic Neuropathy: No longer a “Migraine,” but Still a Headache. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2018;22(7):50. doi:10.1007/s11916-018-0705-5

- Li C, Huang X, Tan X, Fang Y, Yan J. A Clinical Retrospective Study of Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic Neuropathy in Adults. J Ophthalmol. 2021;2021:1-5. doi:10.1155/2021/9213852

- Vijayan N. Ophthalmoplegic Migraine: Ischemic or Compressive Neuropathy? Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 1980;20(6):300-304. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1980.hed2006300.x

- Lance J, Zagami A. Ophthalmoplegic Migraine: A Recurrent Demyelinating Neuropathy? Cephalalgia. 2001;21(2):84-89. doi:10.1046/j.1468-2982.2001.00160.x

- Lal V, Sahota P, Singh P, Gupta A, Prabhakar S. Ophthalmoplegia With Migraine in Adults: Is It Ophthalmoplegic Migraine? Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain. 2009;49(6):838-850. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2009.01405.x

- Friedman D. The ophthalmoplegic migraines: A proposed classification. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(6):646-647. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2009.02004.x

- Aleksic D, Drakulic S, Ljubisavljevic S. Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic Neuropathy: Migraine, Neuralgia, or Something Else? J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2020;34(4):374-378. doi:10.11607/ofph.2656

- Castillejo Becerra CM, Crowson CS, Koster MJ, Warrington KJ, Bhatti MT, Chen JJ. Population-based Rate and Patterns of Diplopia in Giant Cell Arteritis. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2022;46(2):75-79. doi:10.1080/01658107.2021.1965627

- Mantia L La, Curone M, Rapoport A, Bussone G. Tolosa–Hunt Syndrome: Critical Literature Review Based on IHS 2004 Criteria. Cephalalgia. 2006;26(7):772-781. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01115.x

- Takemoto D, Ohkubo S, Udagawa S, Kuroda M, Sugiyama K. A Case of Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic Neuropathy Successfully Treated with Beta-blocker Eye Drop Instillation. Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2021;45(5):320-323. doi:10.1080/01658107.2020.1791190

- Zamproni LN, Ribeiro RT, Cardeal M. Treatment of Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic Neuropathy: A Case Where Pregabalin Was Successfully Employed. Case Rep Neurol Med. 2019;2019:1-5. doi:10.1155/2019/9185603

- Aljammaz AM, Al Orainni H, Alnughaythir AI. Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic Neuropathy Responding to Lamotrigine: A Case Report. Cureus. Published online March 25, 2024. doi:10.7759/cureus.56924

- Petruzzelli MG, Margari M, Furente F, et al. Recurrent Painful Ophthalmoplegic Neuropathy and Oculomotor Nerve Schwannoma: A Pediatric Case Report with Long-Term MRI Follow-Up and Literature Review. Pain Res Manag. 2019;2019:1-11. doi:10.1155/2019/5392945

- Kim R, Kim JH, Kim E, Yang HK, Hwang JM, Kim JS. Oculomotor nerve tumors masquerading as recurrent painful ophthalmoplegic neuropathy: Report of two cases and review of the literature. Cephalalgia. 2015;35(9):825-830. doi:10.1177/0333102414558886

- Shin RK, Mejico LJ, Kawasaki A, et al. Transient Ocular Motor Nerve Palsies Associated With Presumed Cranial Nerve Schwannomas. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2015;35(2):139-143. doi:10.1097/WNO.0000000000000220

- Ramirez M, Talebi R, Puran A, et al. The Association Between Glaucoma Sub-types, Migraines, and Ophthalmoplegic Migraines in California Medicare Beneficiaries. IOVS. 2024;65(7):2440-2440.

Carolyn is a graduate of The Ohio State University College of Optometry and completed her residency year at the Kansas City VA. She now enjoys practicing at the West Texas VA Health Care System serving veterans in rural Texas.