Clinical Decision Making is Difficult

How do we make good decisions for our patients? How do we decide which diagnosis is most appropriate? How do we decide which treatment plan provides the best possible outcome? More fundamentally, how do we decide while uncertain?

Whether we are aware of it or not, a degree of uncertainty exists in nearly every clinical decision. For example, we are not certain of which ocular hypertension patients are going to convert to glaucoma. We are not certain of which patients with “dry” age-related macular degeneration will convert to “wet” age-related macular degeneration. We do not know, which absolute certainty, why a patient’s eyes feel dry and which treatment provides the most lasting relief.

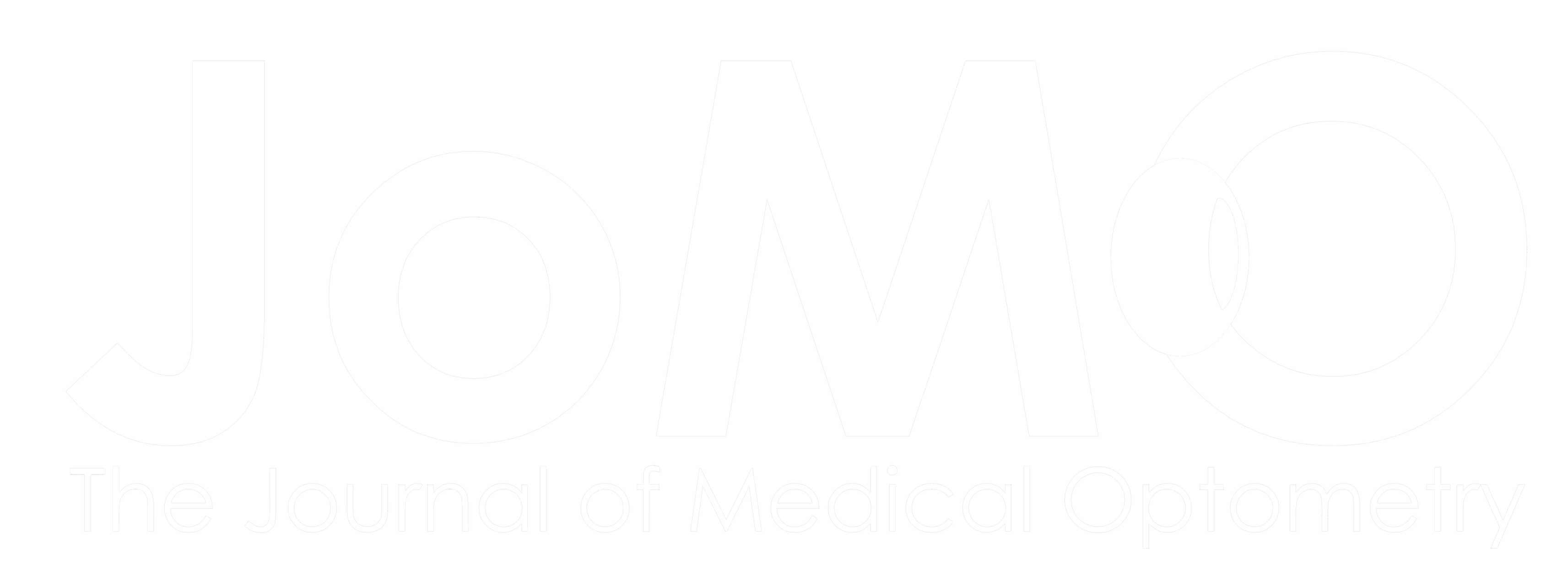

For example, consider a case. A 38 year old, -11.50 D OU established patient presents with new floaters in the right eye. As previously documented, extensive lattice degeneration and an atrophic retinal hole at 9:00 with no surrounding sub-retinal fluid are found on dilated funduscopy. However, a new mild, non-obscuring vitreous hemorrhage near the visual axis is found with an adjacent Weiss ring. However, there is no retinal tear or new retinal abnormality found upon inspection with scleral depression and 3 mirror extended ophthalmoscopy. Shafer’s sign is also negative. What is your diagnosis and management plan? Do you refer the patient to a retinal specialist for potential treatment or monitor closely since no retinal tear was found? As it pertains to our discussion, how do you arrive at that decision? Do you decide based on the results of an applicable research study? Do you decide based on your past experiences or a lecture from an industry expert? Or do you decide based on the patient’s anxiety about a potential loss of vision and preferences for treatment?

Evidence-Based Medicine to the Rescue

Evidence-Based Medicine (EBM), as pioneered by Oxford Professor, David Sackett, is defined as the “conscientious, explicit, and judicious use of current best evidence, combined with individual clinical expertise and patient preferences and values, in making decisions about the care of individual patients.”1,2 That is a mouthful, so let’s clarify.

According to EBM, how do we decide while uncertain? We combine 1) current best evidence, with 2) clinical expertise, according to 3) the patient’s preferences and values. Making good clinical decisions requires the use of all three categories of information. What we will call the 3 pillars of EBM.

In future editions of this column, Follow The Science, we will discuss common misconceptions of EBM and how leaning too heavily on one pillar can mislead our clinical decisions. Of course, being in the Journal of Medical Optometry, we will mostly discuss how to evaluate and apply research evidence. Topics of discussion will include understanding observational research and its role in risk assessment, knowing how to evaluate a randomized controlled trial (RCT), how the hierarchy of evidence applies to clinical practice, how cognitive biases can mislead our decisions, and despite being the gold standard for research, why the RCT may not give us the certainty we think it does.

EBM as a Decision-Making Filter

Back to our case of the highly myopic, 38-year-old with a new vitreous hemorrhage. What was the treatment plan and more importantly why was that treatment plan chosen? Since no new retinal tear was found, the decision was made to monitor the patient by DFE and extended ophthalmoscopy again in two weeks rather than refer them for treatment. The decision was based upon several factors: the American Academy of Ophthalmology Preferred Practice Pattern (for Posterior Vitreous Detachment, Retinal Breaks, and Lattice Degeneration) recommendations for follow-up3, the small study applicable to the case4, the past clinician’s experience and success monitoring vitreous hemorrhages without retinal breaks, and the patient’s trust (built over five years of care) in the clinician’s ability to manage the condition. The patient was evaluated every 2-4 weeks until the vitreous hemorrhage resolved. No new retinal breaks were discovered needing treatment.

Did a wise application of EBM lead to the success of the patient? No, but it led to the judicious, combined use of the available research evidence, clinical expertise, and the patient’s preferences, ultimately leading to an appropriate treatment plan despite the uncertainty of the outcome. This is the power of EBM; to be a filter for making wise clinical decisions despite uncertainty.

References

- Sackett DL, Rosenberg WM, Gray JA, Haynes RB, Richardson WS. Evidence based medicine: whatit is and what it isn’t. BMJ. 1996; 312:71–72.

- Swanson JA, Schmitz D, Chung KC. How to Practice Evidence Based Medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010 July; 126(1):286-294.

- Flaxel CJ, Adelman, RA, Lim JI, et al. Posterior Vitreous Detachment, Retinal Breaks, and Lattice Degeneration PPP 2019. American Academy of Ophthalmology. 2019.

- Sarrafizadeh R, Hassan TS, Ruby AJ, et al. Incidence of retinal detachment and visual outcome in eyes presenting with posterior vitreous separation and dense fundus-obscuring vitreous hemorrhage. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(12):2273-2278.

Dr. Klute owns and practices at Good Life Eyecare, a multi-location practice in Eastern Nebraska and Western Iowa. He is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry and is certified by the American Board of Certification in Medical Optometry. He writes and lectures on primary eye care practice management, evidence-based medicine, glaucoma, and dry eye disease.