ABSTRACT

This brief report reviews the epidemiology, clinical presentation, management, and treatment of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia. It also reviews a case report showing the initial presentation and status post treatment of conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia.

Keywords: neoplasia; conjunctiva; carcinoma; ocular surface

CASE REPORT

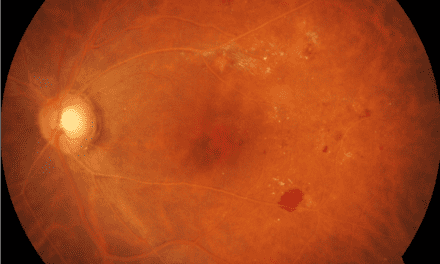

A 76-year old Caucasian male presented with complaints of a newly red eye which started two months ago and blurred vision without glasses. He denied any pain, discomfort, or improvement of redness with artificial tears. He also denied any new flashes, floaters or double vision. His medical history included prostate cancer and hypertension. Visual acuity without correction was 20/50 OD, 20/30 OS which was best corrected to 20/25 OD and 20/25 OS. Extraocular motilities, confrontation visual fields and pupillary responses were normal. Upon slit lamp examination, the right eye was unremarkable but the left eye revealed a large gelatinous, elevated mass on the temporal bulbar conjunctiva near the limbal margin as shown in Figure 1. The size of the lesion was roughly 6 mm vertically and 5 mm horizontally. Due to the size, appearance, and location, the lesion was suspected to be conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and the patient was referred to an ophthalmologist who specializes in cornea and external disease.

Figure 1. Color photograph of the left eye with a large elevated gelatinous appearing mass that is consistent with the appearance of a conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia.

At the referral appointment, the lesion was described as a large leukoplakic lesion at the limbus which measured at 6 mm vertically and 3.5 mm horizontally and the lesion was confirmed to be CIN. The patient was advised on treatment options which included excision with cryopexy and topical drops such as interferon, mitomycin C or 5-fluorouracil (5-FU). He was started on 5-FU four times a day for 1 week in duration and instructed to return in one month for an evaluation.

At the follow-up visit with our clinic, the lesion was reduced in size following treatment with topical 5-FU as seen in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Color photograph of the left eye after treatment

DISCUSSION

Ocular surface squamous neoplasia (OSSN) covers a wide range of ocular diseases that affect the squamous epithelial cells on the surface of the eye. This includes conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia, corneal epithelial dysplasia, squamous cell carcinoma, and mucoepidermoid carcinoma.1 OSSN frequently occurs at the corneoscleral limbus where there are exposed areas of bulbar conjunctiva, typically nasally and temporally.1 The incidence of OSSN is low and ranges from 0.13 to 0.19 per 100,000 persons, but may be higher in those who live closer to the equator.1 It commonly affects older individuals, males, and Caucasians within the US population, but may be more common in younger patients in African populations. Risk factors for developing OSSN include cigarette smoking, ultraviolet light exposure, vitamin A deficiency, chronic inflammation, trauma, HPV, immunosuppression (e.g. HIV) and mutations within the tumor suppressor gene p53.1

Conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia is the most common tumor of the ocular surface and a precursor to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), which is the most common conjunctival malignancy.2 CIN is a non-invasive condition that is slow growing and arises from a single mutated cell on the ocular surface, which usually begins near the limbus.2 Unlike squamous cell carcinoma, CIN leaves the basement membrane intact and the underlying substantia propria is spared which decreases the metastatic potential due to a lack of access to the lymphatics and blood vessels.2 Most patients are unaware of the lesion until they complain of redness, foreign body sensation, irritation or tearing.3

Clinical presentations for CIN can vary and lead to a misdiagnosis for other conjunctival lesions such as pterygium, pinguecula, hemangioma, cyst, pannus, or papilloma. Typically, 95% of CIN lesions will occur at the limbus due to the highly active mitotic cells, and they can appear as a gelatinous or plaque-like lesion with a gray or white appearance.2 They may be flat or elevated and associated with feeder vessels. In contrast, cases of SCC will present similar to CIN but will be an immobile lesion and fairly raised with a large feeder vessel due to break in the epithelial basement membrane.2 By using high resolution anterior segment optical coherence tomography (OCT), clinicians can differentiate between CIN and other conjunctival lesions by evaluating changes in epithelial thickening, stromal involvement, size and depth of the lesion.1 Additionally, anterior segment OCT can be used to define the margins of the tumor and delineate between normal and abnormal tissue. For example, CIN will appear as hyper-reflective with a thickened epithelium and there will be an abrupt transition from normal to abnormal tissue.1 This ability to differentiate between normal and abnormal tissue with OCT allows clinicians to monitor for tumor resolution and minimize the overuse of topical therapy.

The three major clinical variants of CIN are:

- Papilliform lesions will appear as a red-dot or strawberry pattern which is caused by the fibrovascular core of the lesion.4

- Leukoplakia lesions are pre-invasive and will appear as white and thick due to surface hyperkeratinization.4

- Gelatinous lesions, which are the most common variant of CIN, will appear with hairpin configuration of the nearby conjunctival vessels. They can be nodular or diffuse: nodular has well-defined margins while diffuse appears like a chronic conjunctivitis and is less common than nodular.4

Treatment and management of CIN depends on the onset and likelihood of recurrence. Historically, surgical excision with cryotherapy had been considered the standard treatment. However, there are significant complications such as limbal stem cell deficiency and scarring.1 There are now topical treatment options that can be used as first line treatments and have the advantage of treating the entire ocular surface while selectively targeting the tumor cells.

The most common topical treatments are:

- Interferon (IFN) is an immunomodulatory agent and leukocyte-derived protein that enhances the phagocytic and cytotoxic mechanisms which helps to induce cell death, decrease blood vessel apoptosis and inactivate viral RNA.1 These different mechanisms help to aid in the recognition and targeting of neoplastic cells. Currently IFN alpha-2b is being used as a topical or subconjunctival injection to treat OSSN. As a topical medication, it typically comes in a concentration of 1 million IU/ml and dosed as four times per day until resolution.1 On average, it takes roughly 4 months for the lesion to resolve at an efficacy rate of 80-100% and then the medication is used four times a day for an additional month after the lesion is gone.1 The medication is typically well tolerated but some disadvantages to its use are its cost and the need for refrigerated storage and a compounding pharmacy.

- 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) is a chemotherapeutic treatment and a pyrimidine analog that inhibits DNA synthesis and leads to apoptosis by blocking thymidine synthase.1 It is currently used as a topical drop in a 1% concentration and dosed four times a day for seven days followed by 3-4 weeks without treatment.1 It can be repeated in cycles, but most cases resolve after the first or second cycle with an efficacy rate of 80-100%.5 Compared with IFN, 5-FU has a similar resolution, recurrence rate, and it is more cost effective. Possible side effects of treatment with 5-FU are eye pain, redness, swelling, and the development of filamentary keratitis.1

- Mitomycin C (MMC) is also a chemotherapeutic treatment; it was first discovered in the 1950s as an alkylating agent with antineoplastic and antibiotic properties.5 MMC inhibits DNA synthesis and causes cell death.5 It is typically compounded as a concentration of 0.02 or 0.04% with an efficacy rate between 80-100%.5 The dosing is differs depending on the concentration. For example, 0.04% concentration is dosed as 4 times a day in one week-on and one-week off cycles, whereas 0.02% is continuously dosed at 4 times a day for four weeks.5 It has a faster clinical resolution at an average of 4-5 weeks and shorter treatment course for lesions but the side effects are more frequent and severe than with IFN and 5-FU. These side effects include eye pain, epitheliopathy, conjunctivitis, ectropion, corneal toxicity, punctal stenosis, and even scleral melt.5 Therefore, MCC may be reserved for cases non-responsive to other treatment options.

CONCLUSION

Although conjunctival intraepithelial neoplasia has a relatively low mortality rate and low risk for metastasis, it is still important to treat this condition with a sense of urgency due to the increased likelihood of vision loss and limbal stem cell deficiency with corneal involvement. Anterior segment OCT can be used to differentiate between CIN and other benign conjunctival lesions, by evaluating for epithelial activity, stromal invasion, and corneal involvement. Topical treatments, such as IFN, 5-FU, and MCC are now more commonly used as first line treatments due to their effectiveness in treating the entire ocular surface and lower side effect profile as compared to surgical removal.

REFERENCES

1. Patel, Umangi et al. “Update on the Management of Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia.” Current ophthalmology reports vol. 9,1 (2021): 7-15.

2. Krachmer, JH. Mannis, MJ. Holland, EJ. Cornea: Fundamentals, diagnosis and management. 2005.

3. Huerva, V. Ascaso, F. (2012) Intraepithelial Neoplasia InTech. https://doi.org/10.5772/1221

4. Gurnani, B. Kaur, K. Ocular Surface Squamous Neoplasia. StatPearls Publishing; 2023 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK573082/

5. Nanji, Afshan A et al. “Topical chemotherapy for ocular surface squamous neoplasia.” Current opinion in ophthalmology vol. 24,4 (2013): 336-42.

Chillicothe VAMC | Chillicothe, OH

Dr. Njeru is a staff optometrist at the Chillicothe VA Medical Center. He graduated from The Ohio State University: College of Optometry and completed his ocular disease residency at the Chillicothe and Columbus VA. . He is a fellow of the American Academy of Optometry.

Dr. Miller is a staff optometrist at the Chillicothe VA Medical Center. She graduated from The Ohio State University College of Optometry and completed her ocular disease residency at the Chillicothe and Columbus VA.