Perineural Spread of Skin Cancer Presenting With Multiple Cranial Nerve Involvement

Welcome to the “Neuro Nuggets” column within the Journal of Medical Optometry (JoMO)! This column aims to make neuro-ophthalmic disease more approachable by blending real-world clinical cases with evidence-based medicine. The patient in this edition’s column demonstrates the importance of recognizing the potential impact for skin cancer to result in neuro-ophthalmic disease. Enjoy!

Case Presentation

A 74-year-old white male presented with shooting left-sided facial pain, numbness, and a pressure headache behind his left eye that had progressively worsened over a 3 year period. The patient’s medical history was significant for Mohs surgery 4 years prior for removal of basal cell carcinoma (BCC) of the left forehead, hypertension, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression. His ocular history included bilateral laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) and optic disc drusen of both eyes.

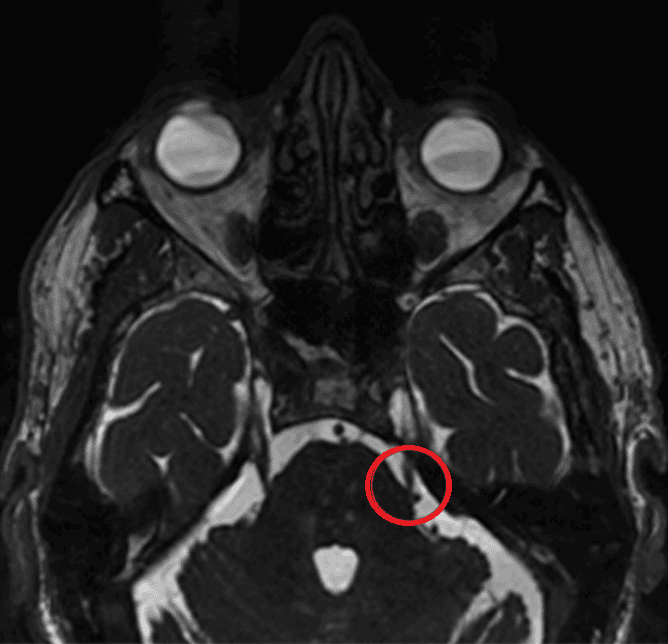

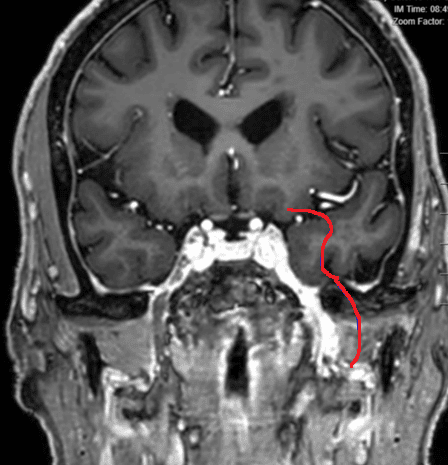

On initial examination, the patient’s best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye. Confrontation visual fields, extraocular muscle motility evaluation, and pupils were normal. Trigeminal nerve evaluation exhibited left-sided 0% sensation along the ophthalmic division (V1), 25% “tingling” sensation along the maxillary division (V2), and 50% sensation along the mandibular division (V3); trigeminal nerve function was intact on the right side (V1-V3). Slit lamp exam and dilated fundus evaluation were unremarkable; there was no significant corneal staining after instillation of fluorescein dye. The patient was co-managed by neurology for presumed trigeminal neuralgia and medically managed with gabapentin. The patient’s initial magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) brain showed intracranial vasculature abutting the left trigeminal nerve, supporting the diagnosis of classical trigeminal neuralgia (Figure 1). Neurosurgery was consulted and did not recommend any surgical intervention at this time.

Figure 1. MRI of the brain showing compression of a vascular structure (likely venous) abutting the lateral aspect of the root entry zone of the left trigeminal nerve. A tiny vascular structure abuts the inferior aspect of the cisternal segment of the right trigeminal nerve.

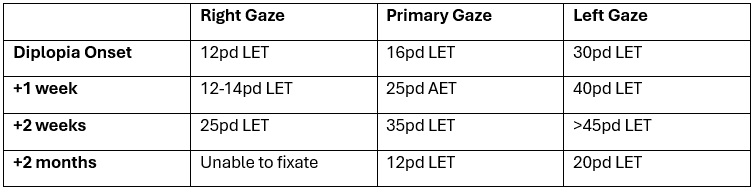

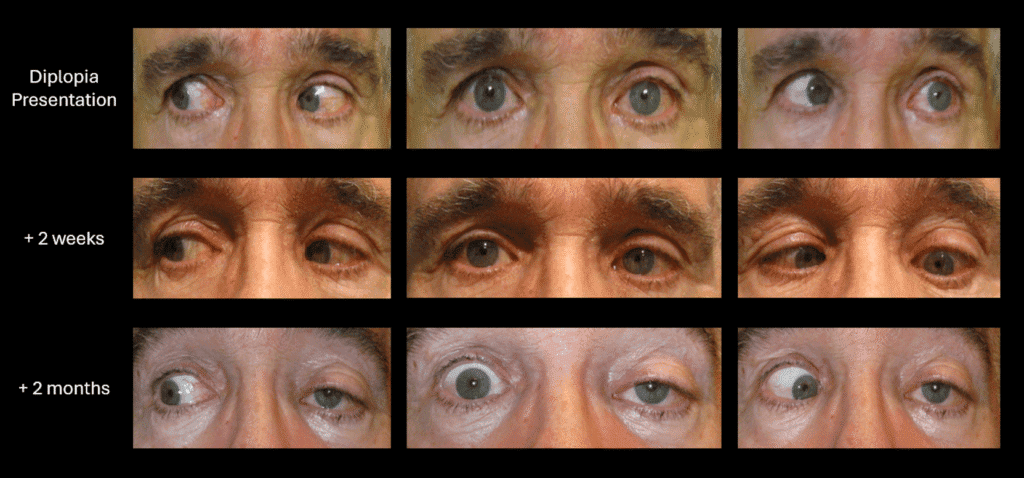

Three months after initial presentation, the patient presented with horizontal binocular diplopia and dizziness. Follow-up brain MRI showed new abnormal enhancement along the distribution of the left trigeminal nerve, extending into the cavernous sinus. His ocular motility and alignment examination raised concern for left abducens nerve palsy (Table 1). All other cranial nerve testing was stable. Fresnel prism (9 base-out left eye) was applied to the patient’s habitual spectacle lenses to alleviate diplopia.

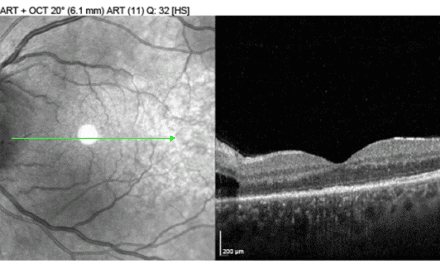

One week later, the patient returned with worsening horizontal diplopia. His ocular motility and alignment demonstrated worsening left eye abduction deficit, particularly in primary and left gaze (Figure 7). The patient also had a mild upper left eyelid ptosis and anisocoria (left pupil smaller than the right pupil), which was greater in dim illumination, raising concern for a left oculosympathetic paresis (Horner’s syndrome). Slit lamp exam showed moderate superficial punctate keratitis in the left eye. The patient was scheduled for a biopsy of the infraorbital branch of the left maxillary nerve, where enhancement was seen most predominantly on neuroimaging and deemed the most accessible for surgery.

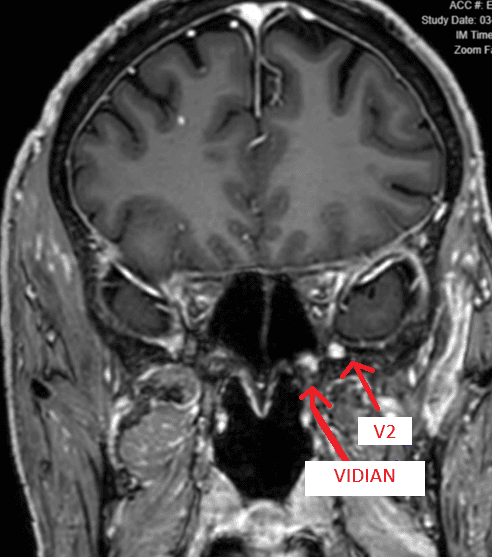

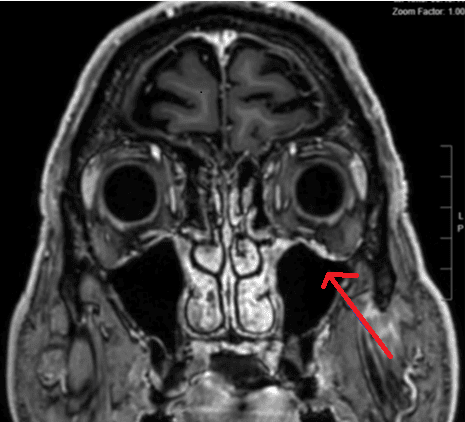

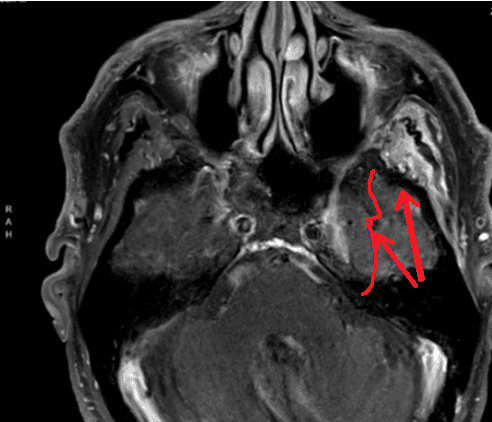

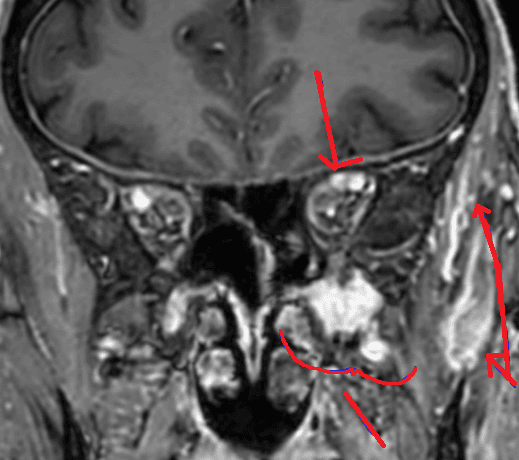

The patient was diagnosed with perineural spread of skin cancer, likely from a prior left forehead basal cell carcinoma or a possible squamous cell carcinoma elsewhere. The left infraorbital nerve biopsy was inconclusive for basal cell vs squamous cell. Multiple cranial nerves were now involved per neuroimaging from his outside team: the left trigeminal, left abducens, left Vidian, and suspected left facial nerve (Figures 2-6).

Figure 2. Contrast-enhanced brain MRI showing abnormal, asymmetric enhancement of the left cavernous sinus.

Figure 3. Contrast-enhanced brain MRI showing abnormal, asymmetric enhancement of the left infraorbital branch of the maxillary nerve.

Figure 4. Contrast-enhanced MRI brain showing abnormal enhancement of the left supraorbital branch of V1 trigeminal nerve, cavernous sinus and V1, V2 and V3 branches. Denervation edema was also present, involving the left muscles of mastication.

Figure 5. Contrast-enhanced MRI brain demonstrating significant enhancement in the left Meckel’s cave and extending through foramen ovale into the masticator space.

Two months after the onset of diplopia, the patient returned with worsening drooping of the left upper eyelid and subjectively improved symptoms of diplopia. Visual acuity was now decreased from 20/20 to 20/30 in the left eye. Ocular motility and alignment testing revealed 0% left abduction ability, 5% adduction ability, and restricted supra-duction and infra-duction, all suggesting new left oculomotor nerve involvement (Table 1, Figure 7). Trigeminal nerve testing showed further reduced sensation of V2 and V3 to 0% and 50% sensation, respectively. Ocular lubricants were prescribed. The patient was recommended to have treatment by focal radiation of the cavernous sinus lesion and checkpoint inhibitor infusions via his neuro-oncology providers and is currently undergoing treatment.

Figure 7. Ocular alignment in primary and secondary gazes over time. Note progressive left upper eyelid ptosis.

Discussion

When a patient presents with pain along the trigeminal nerve pathway, there are many associated conditions to consider. Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is a chronic pain condition afflicting one or more distributions of the trigeminal nerve. The pain typically presents as abrupt unilateral shock-like, stabbing pain most often along the V2 or V3 pathway. Isolated symptoms along V1 are rare (<5% of cases) and typically associated with additional lacrimation, rhinorrhea, and conjunctival injection.1,2 However, the patient in this report demonstrated some atypical features that were not consistent with trigeminal neuralgia. If trigeminal pain is associated with numbness, then other conditions must be considered, especially in patients with a history of facial skin cancer. Specifically, the combination of progressive pain and sensory loss in the same area is called anesthesia dolorosa and is highly concerning for perineural spread of malignancy along trigeminal nerve branches. A thorough systemic history, trigeminal nerve sensitivity testing, anterior segment examination, and neuroimaging studies are essential to rule out masqueraders and ensure prompt disease recognition and treatment.

Patients with a history of skin cancer, adenoid cystic carcinoma, lymphoma, and other types of cancer can be at higher risk for the development of perineural invasion (PNI) and perineural spread (PNS). Perineural invasion is a microscopic finding in which tumor cells are found within or around the perineural space, while perineural spread is a radiologic finding where tumor cells are found to be traveling along a larger named nerve over a long distance.3 There is little known about the mechanism of transition from PNI to PNS, but PNS most commonly exhibits clinical symptoms. Patients may initially experience mild formication (the sensation of bugs crawling on their skin), later developing pain and sensory impairment.3 Motor nerve dysfunction will eventually emerge as tumor growth extends, causing jaw deviation or weakness of the trigeminally innervated muscles of mastication. Involvement of larger nerves >0.1 mm in diameter produces symptoms of hypoesthesia and dysesthesia, mimicking trigeminal neuralgia or Bell’s palsy if CN5 and CN7 are affected.4 The Vidian nerve contains CN7 parasympathetics (greater superior petrosal nerves) and sympathetics (lesser superior petrosal nerves); the patient in this report demonstrated abnormal enhancement of these structures, potentially stemming from involvement of the geniculate ganglion of CN7.

The closely integrated neural network in the face puts patients at increased risk for PNS development in the head and neck region.3 Therefore, PNS should be considered in patients with a history of skin carcinoma and atypical trigeminal neuralgia who develop other cranial nerve dysfunction/numbness along nerve pathways. PNS is a rare finding in those with skin carcinomas (<5% of cases) and is most closely associated with cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma (SCC).4 Prognosis is variable and depends primarily on the causative agent and the size or extension of the nerve involved.5 As tumor cells spread to “meeting points” of other nerves, such as the cavernous sinus, the prognosis worsens.3 Tumor cells may migrate along other nerves, potentiating infiltration of the surrounding venous blood.

On neuroimaging, PNS characteristically shows abnormal enlargement or enhancement of the affected nerve through the associated foramen.3 The existing fat plane surrounding the nerve will be diminished, adjacent muscle denervation can develop, and the exiting foramen may also be eroded.3,6 It is important to detect PNS radiologically as early as possible if clinical signs are exhibited, as prognosis worsens if more nerves become involved. Cases are normally treated aggressively with radiotherapy followed by chemotherapy as needed.

As for the patient in this case, the neuroimaging performed when the patient developed symptoms atypical for trigeminal neuralgia (formication and numbness along V2/V3) was key in the diagnosis of PNS. His MRI exhibited classic abnormal enhancement of the intracranial and extracranial left trigeminal nerve and its branches, extending from the nerve root entry zone, through the cisternal segment as well as within Meckel’s cave and along trigeminal nerve branches. Upon sequential follow-ups, he developed double vision and oculosympathetic paresis as cutaneous basal cell carcinoma cells spread, involving left CN3, CN6, CN7, and the Vidian nerve. The patient underwent sequential radiotherapy and is currently undergoing chemotherapy at the time of case report submission.

Clinical Pearls

- Numbness or hypesthesia along the distribution of the trigeminal nerve are red flags in patients diagnosed with presumed trigeminal neuralgia

- Perineural invasion of skin cancer is a known complication of SCC (and less commonly BCC), and may manifest with ocular motility deficits or trigeminal nerve dysfunction

- Signs of perineural invasion and cranial nerve dysfunction may be more apparent on clinical exam than neuroimaging in early stages

- Fresnel prism may be a helpful tool to temporarily relieve symptoms in patients with diplopia

Resources

- Gambeta E, Chichorro J, Zamponi G. Trigeminal neuralgia: an overview from pathophysiology to pharmacological treatments. Molecular Pain 2020.

- Davis K, DeSouza D, Hodaie M. Structural Magnetic Resonance Imaging Can Identify Trigeminal System Abnormalities in Classical Trigeminal Neuralgia. Front. Neuroanat. 2016. 10:95

- Medvedev O, Hedesiu M, Ciurea A, et al. Perineural spread in head and neck malignancies: imaging findings – an updated literature review. Bosnian Journal of Basic Medical Sciences. Published online June 29, 2021. doi:https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2021.5897

- Balamucki CJ, DeJesus R, Galloway TJ, et al. Impact of Radiographic Findings on For Prognosis Skin Cancer With Perineural Invasion. American Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2013;38(3):248-251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/coc.0b013e3182940ddf

- Sherwani Y, Aldana PC, Khachemoune A. Squamous and basal cell carcinoma with perineural invasion: pathophysiology and presentations. International Journal of Dermatology. 2021;61(6):653-659. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/ijd.15817

- Amram AL, Hertzing WJ, Smith SV, Chévez-Barrios P, Lee AG. Perineural spread of basosquamous carcinoma to the orbit, cavernous sinus, and infratemporal fossa. Orbit. 2017;37(2):110-114. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01676830.2017.1383462