A Crystal Conundrum: Differential Diagnoses for Crystalline Retinopathy and Features of OCT Angiography in Macular Telangiectasia Type 2

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Crystalline retinopathies have been associated with inherited disease, toxic, and idiopathic etiologies. Macular telangiectasia (MacTel) type 2 is a disease characterized by abnormal vessel development and neuronal degeneration within the macula. Intraretinal crystals are frequently observed in MacTel and may appear at any stage. Identifying optical coherence tomography (OCT) angiography features along with these crystals may aid in early diagnosis of MacTel.

CASE REPORT

A dilated examination on a 65-year-old white male revealed bilateral intraretinal crystalline deposits concentrated in the temporal macula. OCT with angiography (OCT-A) showed dilated, telangiectatic vessels present within the deep retinal capillary plexus of each eye. Inner retinal hyporeflective cavities and internal limiting membrane drape were noted bilaterally on OCT. Given the clinical picture, macular telangiectasia type 2 was diagnosed.

CONCLUSION

Several conditions may be implicated in the development of crystalline retinopathy, including retinal degenerative diseases like MacTel. This case report will highlight multimodal features of MacTel using color fundus photography, OCT, and OCT-A. A brief review of differential diagnoses for crystalline retinopathy will also be presented in this report.

Keywords: crystalline retinopathy, fundus photography, macular telangiectasia type 2, optical coherence tomography, optical coherence tomography angiography, ciliary neurotrophic factor

INTRODUCTION

Crystalline retinopathies have been associated with inherited disease, toxic, and idiopathic etiologies.1 Depending on the underlying disease process, these crystals may be located within various layers of the retina or choroid.2 Macular telangiectasia (MacTel) type 2 frequently presents with intraretinal crystals along with the characteristic abnormal vessel development.2 Although the pathophysiology of MacTel is not clearly elucidated, recent consensus suggests early dysfunction or degeneration of Müller cells as a primary cause. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) and OCT angiography (OCT-A) enable clinicians to identify subtle disease features to aid in diagnosis.3 This report will discuss differential diagnoses of crystalline retinopathy. Multimodal characteristics of MacTel using color fundus photography, OCT, and OCT-A will also be highlighted.

CASE REPORT

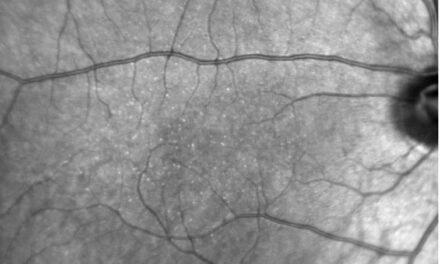

A 65-year-old white male presented for a routine eye exam with concerns of mild distance blur in each eye, slowly progressing over the past six months. His previous ocular history was remarkable for mild age-related cataracts and dry eye syndrome. There was no history of ocular surgery or trauma. His medical history included psoriasis, hyperlipidemia, and stage 3 kidney disease. There was no history of intravenous drug or tamoxifen use. The best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in the right and left eyes. Extraocular movements were full. Confrontation fields were full to finger count. Pupil assessment was unremarkable. Slit lamp biomicroscopy revealed mild age-related cataracts and signs of dry eye syndrome. Dilated fundus examination revealed bilateral intraretinal crystalline deposits within the superior and inferior macula, more densely temporally. Retinal vasculature in the macular region appeared normal (Figure 1A-D).

OCT imaging revealed the presence of temporal inner retinal hyporeflective cavities and internal limiting membrane (ILM) drape with early signs of outer retina disruption in each eye (Figure 2A-D). OCT-A showed mild capillary dropout between vessels and telangiectasia temporally within the superficial retinal capillary plexus (SCP) (Figure 3A). The deep retinal capillary plexus (DCP) images displayed temporal foveal avascular zone (FAZ) extension with adjacent telangiectasia (Figure 3B). OCT-A features were similar bilaterally, although scan quality was poor for the right eye. While funduscopic findings outside of the crystalline deposits were unremarkable, the OCT findings and subtle vascular changes noted with OCT-A were consistent with a diagnosis of macular telangiectasia type 2.

The patient was educated that while no treatment is currently warranted, it is important to monitor his ocular health routinely for the development of neovascularization. He was scheduled for a two-week follow-up examination to monitor for progression and establish a clearer clinical picture with additional imaging. Fundus autofluorescence (FAF) was attempted at this visit, though the images were not clear enough to definitively show hypofluorescent macular findings consistent with MacTel. Otherwise, the OCT and fundus findings remained stable. The patient was referred to a vitreoretinal specialist for further evaluation with possible fluorescein angiography (FA).

He was examined by the vitreoretinal specialist approximately three months later. The report noted similar findings as the previous exams. FA testing was not performed at the visit, but the specialist did corroborate the diagnosis of MacTel. The patient was scheduled for a six-month follow up appointment for re-evaluation.

Figure 1. Color fundus images of the right (A) and left (B) eyes with crystalline retinopathy. Expanded views of the right (C) and left (D) maculae display intraretinal crystals arranged along the nerve fiber layer and appear to break near the horizontal raphes.

Figure 2. B-scan OCT imaging of the right (A) and left (B)eyes. Temporal hyporeflective cavities and ILM drape are present in each eye (yellow arrows). Possible early collapse and disruption of the outer retina temporal to the fovea of the right eye (C, yellow circle). Early disruption of the outer retina temporal to the fovea of the left eye (D, yellow oval).

Figure 3. Left eye en face OCT-A imaging. (A) Superficial retinal capillary plexus showing trace temporal loss of capillary density. (B) Deep retinal capillary plexus shows enlargement of the foveal avascular zone temporally with adjacent telangiectasia. These vascular changes are adjacent to the hyporeflective cavity noted on OCT. (C) The avascular outer retina exhibits no abnormal capillary invasion within the background noise.

DISCUSSION

Macular telangiectasia is a condition characterized by atypical retinal blood vessel formation and neurodegeneration. MacTel is typically bilateral, although not always symmetrical, with the second eye often presenting later. There is no gender predilection, and onset is typically in the 5th decade of life. It is estimated to affect about 0.1% of the population.4 Recent evidence points towards a neurodegenerative etiology of MacTel and involvement of Müller cells, which provide nutrients that are responsible for producing and releasing neurotrophic factors such as ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF). CNTF provides protection against cell atrophy. Therefore, Müller cell dysfunction or degeneration can cause nutritional deprivation and subsequent retinal atrophy. This leads to hypoxia and, in turn, causes vascular endothelial growth factor secretion and telangiectatic blood vessel formation.4–6

According to The MacTel Project, an international multi-center prospective study of MacTel, 46% of patients had signs of crystalline deposits located at the anterior surface of the nerve fiber layer (NFL).7 They used adaptive optics scanning laser ophthalmoscope imaging to show crystals distributed parallel to bundles of ganglion cell axons within the NFL. This is relevant not only because of the presence of crystals, but also the amount of crystals show statistically significant associations with the loss of retinal transparency.7 In early stages of MacTel, retinal crystals are distributed in an annular pattern within a 4000 micron diameter of the fovea, sparing the central 700 microns, and often beginning in the temporal macula. The crystals were located along the ganglion cell axons in the NFL, a pattern only seen in MacTel and Sjögren-Larsson Syndrome. However, late-stage MacTel crystal arrangement is nonspecific.4,8 The crystals often are less dense in areas near the horizontal raphe and immediately around the fovea as was consistent with this case (Figure 1C-D).7

Crystalline retinopathy is a group of diseases that have associated crystalline deposits in the preretinal, intraretinal, and/or subretinal spaces of the retina. The composition of the crystal varies, depending on the etiology of the crystalline deposit. The etiology of development includes genetic, toxic, and idiopathic causes.2 Table 1 lists a breakdown of crystalline retinopathy differential diagnoses along with clinical features of each condition.1,9–17

Genetic differential diagnoses for crystalline retinopathy include but are not limited to: Bietti crystalline dystrophy, cystinosis, oxalosis, Sjögren-Larson syndrome, and Kellin syndrome.1 For patients presenting with crystals in the retina in the first three decades of life, it is best to consider a likely genetic condition.9 Sjögren-Larson syndrome patients often present with colobomatous microphthalmia and congenital cataracts, so a lack of these signs would indicate a higher likelihood for MacTel.18 Toxic differential diagnoses include: tamoxifen, canthaxanthin, talc, methoxyflurane, and nitrofurantoin.1 A thorough medication history should be taken to identify any toxic associations. Tamoxifen, a breast cancer drug, is often needed for critical health care, and many of these patients do not have significant recovery after discontinuing the drug. Therefore, prevention by monitoring closely with OCT and dilated fundus exams is typically the best method of care.9 Idiopathic causes such as West African crystalline maculopathy have been localized to a native Nigerian Igbo tribe, so a lack of association with this tribe can rule out this differential.1

Multimodal imaging, including OCT, OCT-A, and fundus photography, can be used together to help differentiate MacTel from other forms of crystalline retinopathy.19,20 The identification and management of MacTel is important since it has the potential to develop sight-threatening subretinal neovascularization, retinal atrophy, and macular holes.9 OCT imaging most commonly exhibits temporal foveal changes of thinning and atrophy of the outer retina, hyporeflective cavitations in the inner and outer retinal layers, and ILM drape.21 Collapse of the outer retinal layers, specifically the central ellipsoid zone (EZ) loss, has been associated with poorer visual prognosis in MacTel.22,23 OCT imaging is also particularly helpful in differentiating drusen from crystals when seen with dilated fundus examination.9

FAF imaging may be useful to detect early stages of MacTel with mild increases in foveal autofluorescence seen even before clinical or angiographic abnormalities are present. This is thought to be partially attributed to the loss of macular pigments, lutein and zeaxanthin, which typically mask FAF wavelengths.4 As MacTel advances, autofluorescence typically increases before pigment migration, causing patches of increased and decreased fluorescence to appear in the last stage.7,24,25 The mechanism of pigment loss associated with MacTel remains to be elucidated, however, loss may be due to dysfunctional storage capabilities or secondary to structural alterations that disrupt pigment trafficking within the macula. Evidently, zeaxanthin appears to be more commonly deficient compared to lutein, underpinning a possible loss of the ability of the retina to convert lutein to zeaxanthin.26

OCT-A is a non-invasive imaging method that measures the movement of blood cells, allowing for en face reconstruction of retinal and choroidal capillary network flow maps. It has advantages compared to fluorescein angiography, which has a wide-field examination, but requires dye injection and layers beyond the SCP are poorly differentiated.21,27 The ability to distinguish inner and outer retinal vasculature with OCT-A can be important for visualizing early vessel changes in MacTel.27 Changes within the DCP, as seen on OCT-A imaging, have been observed to be affected first in MacTel, even prior to when structural OCT abnormalities arise.3 As progression occurs, the SCP, as seen on OCT-A imaging, can become involved.4,23 OCT-A alterations within these plexuses have a predilection for the temporal juxtafoveal area which may exhibit telangiectasia, reduced capillary density, tortuosity, and right-angled vessels.21,27 The FAZ within the SCP or DCP layers may suffer from shape irregularities, new vessel invasion, or dragging of vessels perifoveally.4,21

Vascular structures may become apparent within the typically avascular outer retina. These may appear as bright spots, radially arranged vessels, or loops adjacent to vascular abnormalities in the overlying DCP. However, caution should be used when interpreting the outer retina on OCT-A, especially when retinal atrophy is present. Inaccurate segmentation may cause DCP vasculature to appear as “new” vessels in these layers.27 In this case, no outer retinal vasculature change was observed among the background noise (Figure 3C).

Neovascular MacTel presents as well-demarcated vasculature within the level of the outer retina, retinal pigmented epithelium, and choriocapillaris on OCT-A. These neovascular complexes are most often located near the temporal subretinal fovea which can sometimes anastomose with choroidal vessels in later stages. Neovascular complex formation in MacTel is thought to originate from retinal vasculature, possibly from capillary proliferation within the DCP, as opposed to the choroidal neovascularization found in age-related macular degeneration.27

FA has historically served as the gold standard for diagnosing MacTel, with Gass and Blodi establishing the foundational classification system based on fundus and FA characteristics.28 Recently, Toto et al. developed a OCT-A grading scale for MacTel (Table 2) which has demonstrated strong correlation with FA staging.29 Notably, emerging evidence suggests that OCT-A is superior to FA in reliably detecting neovascularization.29,30

The ability to identify capillary proliferation within the outer retina using OCT-A holds significant clinical importance for MacTel management, as this finding correlates with underlying EZ loss, a recognized prognostic factor for vision deterioration.31 These OCT-A findings enable better patient counseling regarding visual outcomes and guide more frequent monitoring to detect potential vessel extension into the choroid and subsequent exudation. Neovascular MacTel warrants prompt referral to a vitreoretinal specialist for consideration of therapeutic intervention. Intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor injections have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of MacTel.4

Recent evidence shows the benefits of delivering ciliary neurotrophic factor (CNTF) to the vitreous and retina through an encapsulated semipermeable membrane. This allows CNTF to diffuse nutrients to the cells but prevents the host immune system from attacking the CNTF cells. In March 2025, CNTF delivery received FDA approval for delivery via an implant for the treatment of Mac Tel type 2. It is the first cell-based neuroprotective treatment for any neurodegenerative retinal disease or central nervous system disorder.6,32 This device showed between a 30.6% and 54.8% reduction in the rate of ellipsoid zone loss, leading to a slowdown of the loss of photoreceptors. Functionally, this device showed improvement via microperimetry, a retinal test of sensitivity to light response. However, in reading speeds, there was a mixed outcome as compared to the control group.33

For this case, the temporal vessel changes within the macula are consistent with grade 1 MacTel based on the classification outlined in Table 2. Although FAF images obtained at the follow up were unable to supplement the clinical picture clearly, recent literature supports the qualitative vessel findings (e.g. temporal vessel rarefaction and telangiectasia within the DCP and SCP) as hallmark characteristics of MacTel identified through OCT-A.3,20,21,29–31 The fundus and OCT findings further substantiate the diagnosis. While no treatment was indicated at follow-up, referral to a vitreoretinal specialist and possible subsequent FA may still prove beneficial for ongoing management, with FA providing additional diagnostic value as the traditional gold standard for MacTel assessment. This case demonstrates the utility of multimodal imaging, readily available in many optometric practices, for identifying early signs of MacTel and differentiating among crystalline retinopathies.

CONCLUSION

Many types of crystalline retinopathies may be encountered with a myriad of different etiologies. Careful clinical examination and a thorough history is required to make an accurate diagnosis. The advent of OCT-A has given clinicians new technology to assess the details of retinal vasculature in an easy, non-invasive, and frequently repeatable manner. Microvascular changes within the DCP may be one of the earliest signs of MacTel. The ability of OCT-A to distinguish the SCP, DCP, and choroidal vasculature in conjunction with OCT and FAF imaging allow for the ability to readily diagnose and monitor conditions such as MacTel.

REFERENCES

- Drenser K, Sarraf D, Jain A, Small KW. Crystalline Retinopathies. Surv Ophthalmol. 2006 Nov 1;51(6):535–49.

- Kovach JL, Isildak H, Sarraf D. Crystalline retinopathy: Unifying pathogenic pathways of disease. Surv Ophthalmol. 2019 Jan 1;64(1):1–29.

- Chandran K, Giridhar A, Gopalakrishnan M, Sivaprasad S. Microvascular changes precede visible neurodegeneration in fellow eyes of patients with asymmetric type 2 macular telangiectasia. Eye Lond Engl. 2022 Aug;36(8):1623–30.

- Kedarisetti KC, Narayanan R, Stewart MW, Reddy Gurram N, Khanani AM. Macular Telangiectasia Type 2: A Comprehensive Review. Clin Ophthalmol Auckl NZ. 2022;16:3297–309.

- Newman E, Reichenbach A. The Müller cell: a functional element of the retina. Trends Neurosci. 1996 Aug;19(8):307–12.

- Chew EY, Clemons TE, Peto T, Sallo FB, Ingerman A, Tao W, et al. Ciliary neurotrophic factor for macular telangiectasia type 2: results from a phase 1 safety trial. Am J Ophthalmol. 2015 Apr;159(4):659-666.e1.

- Sallo FB, Leung I, Chung M, Wolf-Schnurrbusch UEK, Dubra A, Williams DR, et al. Retinal crystals in type 2 idiopathic macular telangiectasia. Ophthalmology. 2011 Dec;118(12):2461–7.

- Fuijkschot J, Cruysberg JRM, Willemsen MAAP, Keunen JEE, Theelen T. Subclinical Changes in the Juvenile Crystalline Macular Dystrophy in Sjögren–Larsson Syndrome Detected by Optical Coherence Tomography. Ophthalmology. 2008 May 1;115(5):870–5.

- Tenney S, Oboh-Weilke A, Wagner D, Chen MY. Tamoxifen retinopathy: A comprehensive review. Surv Ophthalmol. 2024 Feb;69(1):42–50.

- Espaillat A, Aiello LP, Arrigg PG, Villalobos R, Silver PM, Cavicchi RW. Canthaxanthine Retinopathy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1999 Mar 1;117(3):412–412.

- Novak MA, Roth AS, Levine MR. Calcium oxalate retinopathy associated with methoxyflurane abuse. Retina [Internet]. 1988;8(4). Available from: https://journals.lww.com/retinajournal/fulltext/1988/08040/calcium_oxalate_retinopathy_associated_with.2.aspx

- Shah VA, Cassell M, Poulose A, Sabates NR. Talc Retinopathy. Ophthalmology. 2008 Apr 1;115(4):755-755.e2.

- Ibanez HE, Williams DF, Boniuk I. Crystalline Retinopathy Associated With Long-term Nitrofurantoin Therapy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994 Mar 1;112(3):304–5.

- Saatci AO, Ataş F, Çetin GO, Kayabaşı M. Diagnostic and Management Strategies of Bietti Crystalline Dystrophy: Current Perspectives. Clin Ophthalmol Auckl NZ. 2023;17:953–67.

- Kowalczyk M, Toro MD, Rejdak R, Załuska W, Gagliano C, Sikora P. Ophthalmic Evaluation of Diagnosed Cases of Eye Cystinosis: A Tertiary Care Center’s Experience. Diagn Basel Switz. 2020 Nov 7;10(11).

- Fielder AR, Garner A, Chambers TL. Ophthalmic manifestations of primary oxalosis. Br J Ophthalmol. 1980 Oct;64(10):782–8.

- Browning DJ. West African crystalline maculopathy. Ophthalmology. 2004 May 1;111(5):921–5.

- Jack LS, Benson C, Sadiq MA, Rizzo WB, Margalit E. Segmentation of Retinal Layers in Sjögren–Larsson Syndrome. Ophthalmology. 2015 Aug 1;122(8):1730–2.

- Chew EY, Peto T, Clemons TE, Sallo FB, Pauleikhoff D, Leung I, et al. Macular Telangiectasia Type 2: A Classification System Using MultiModal Imaging MacTel Project Report Number 10. Ophthalmol Sci. 2023 June;3(2):100261.

- Charbel Issa P, Heeren TFC, Kupitz EH, Holz FG, Berendschot TTJM. Very early disease manifestations of macular telangiectasia type 2. Retina Phila Pa. 2016 Mar;36(3):524–34.

- Nalcı H, Şermet F, Demirel S, Özmert E. Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography Findings in Type-2 Macular Telangiectasia. Turk J Ophthalmol. 2017 Oct;47(5):279–84.

- Kim YH, Chung YR, Oh J, Kim SW, Lee CS, Yun C, et al. Optical coherence tomographic features of macular telangiectasia type 2: Korean Macular Telangiectasia Type 2 Study-Report No. 1. Sci Rep. 2020 Oct 6;10(1):16594.

- Runkle AP, Kaiser PK, Srivastava SK, Schachat AP, Reese JL, Ehlers JP. OCT Angiography and Ellipsoid Zone Mapping of Macular Telangiectasia Type 2 From the AVATAR Study. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2017 July 1;58(9):3683–9.

- Wong WT, Forooghian F, Majumdar Z, Bonner RF, Cunningham D, Chew EY. Fundus autofluorescence in type 2 idiopathic macular telangiectasia: correlation with optical coherence tomography and microperimetry. Am J Ophthalmol. 2009 Oct;148(4):573–83.

- Pauleikhoff L, Heeren TFC, Gliem M, Lim E, Pauleikhoff D, Holz FG, et al. Fundus Autofluorescence Imaging in Macular Telangiectasia Type 2: MacTel Study Report Number 9. Am J Ophthalmol. 2021 Aug;228:27–34.

- Charbel Issa P, van der Veen RLP, Stijfs A, Holz FG, Scholl HPN, Berendschot TTJM. Quantification of reduced macular pigment optical density in the central retina in macular telangiectasia type 2. Exp Eye Res. 2009 June 15;89(1):25–31.

- Zeimer M, Gutfleisch M, Heimes B, Spital G, Lommatzsch A, Pauleikhoff D. Association between changes in macular vasculature in optical coherence tomography- and fluorescein-angiography and distribution of macular pigment in type 2 idiopathic macular telangiectasia. Retina Phila Pa. 2015 Nov;35(11):2307–16.

- Gass JD, Blodi BA. Idiopathic juxtafoveolar retinal telangiectasis. Update of classification and follow-up study. Ophthalmology. 1993 Oct;100(10):1536–46.

- Toto L, Di Antonio L, Mastropasqua R, Mattei PA, Carpineto P, Borrelli E, et al. Multimodal Imaging of Macular Telangiectasia Type 2: Focus on Vascular Changes Using Optical Coherence Tomography Angiography. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2016 July 13;57(9):OCT268–76.

- Zhang Q, Wang RK, Chen CL, Legarreta AD, Durbin MK, An L, et al. Swept-source optical coherence tomography angiography of neovascular macular telangiectasia type 2. Retina Phila Pa. 2015 Nov;35(11):2285–99.

- Gaudric A, Krivosic V, Tadayoni R. Outer retina capillary invasion and ellipsoid zone loss in macular telangiectasia type 2 imaged by optical coherence tomography angiography. Retina Phila Pa. 2015 Nov;35(11):2300–6.

- Duncan Jacque L. Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor — A Promising New Therapy for Macular Telangiectasia Type 2. NEJM Evid. 2025 July 22;4(8):EVIDe2500127.

- Chew Emily Y., Gillies Mark, Jaffe Glenn J., Gaudric Alain, Egan Cathy, Constable Ian, et al. Cell-Based Ciliary Neurotrophic Factor Therapy for Macular Telangiectasia Type 2. NEJM Evid. 2025 July 22;4(8):EVIDoa2400481.