The “Not So Easy” Orbital Floor Fracture Case

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Orbital floor fractures are a common finding in facial and head trauma. Usually diagnosed with a maxillofacial CT scan, some orbital floor fractures, like “trap door” fractures, are insidious and could easily be missed. Common symptoms of orbital floor fractures include pain, ecchymosis, diplopia and facial hypoesthesia on the side of the fracture. Particular caution should be taken to assess orbital fracture patients with symptoms of nausea, lightheadedness, dizziness and weakness as this might be suggestive of oculocardiac reflex activation.

CASE REPORT

The young patient in this case report was initially diagnosed with a small orbital floor fracture. The patient was subsequently discharged with conservative treatment (ice packs, ibuprofen). The patient returned to the emergency department the same evening after fainting at home. Showing signs of bradycardia, activation of the oculocardiac reflex was suspected. Emergent surgical intervention of the orbital floor fracture was completed by an oculoplastic surgeon and the patient is now doing well.

CONCLUSION

Orbital fractures or potential orbital fractures should be approached systematically: imaging (maxillofacial CT), visual acuity, pupil evaluation, meticulous EOM testing, IOP evaluation and dilated fundus examination. The clinician, or team of clinicians (ophthalmologists, optometrists, oculoplastic surgeons, ER physicians, radiologists), often work together to provide the best patient outcomes by assessment and management of complications such as activation of the oculocardiac reflex.

Keywords: orbital floor fracture, trap door fracture, oculocardiac reflex, orbital ecchymosis

INTRODUCTION

Orbital floor fractures are a very common injury following blunt facial trauma. Although most orbital floor fractures are relatively simple to diagnose with a maxillofacial CT, some orbital fractures can be easily missed due to their small size or their “trap door” appearance. Trap door fractures, also known as a “white-eyed blowout fracture” occur when the orbital floor is displaced minimally and returns to its original position. Symptoms of orbital floor fractures can include pain, eyelid swelling, decreased visual acuity, blepharoptosis, diplopia (especially in upgaze), hypoesthesia in the distribution of the infraorbital nerve and epistaxis.1,2 Particular attention should be paid to symptoms of nausea, lightheadedness, dizziness and weakness. These signs could reveal activation of the oculocardiac reflex (OCR), a potentially life-threatening complication that can lead to sinus bradycardia, arterial pressure reduction, arrhythmia, asystole and even cardiac arrest and death.3,4,5

CASE REPORT

A 12-year-old, Asian male in good health presented to the Emergency Department with a history of getting elbowed in his eye during a basketball game. Preliminary emergency room reports showed normal body temperature (98.4 F), age-appropriate weight and height and a resting radial pulse of 48 bpm. Their exam found uncorrected visual acuity of 20/20 in each eye. Pupils were equal, round and reactive. There was no evidence of an afferent pupillary defect. Extraocular muscle movements (EOMs), as per the emergency room attending, revealed a possible inability to elevate the right eye in the presence of mild periorbital edema. The patient also reported pain on eye movement as well as double vision “especially when looking up.”

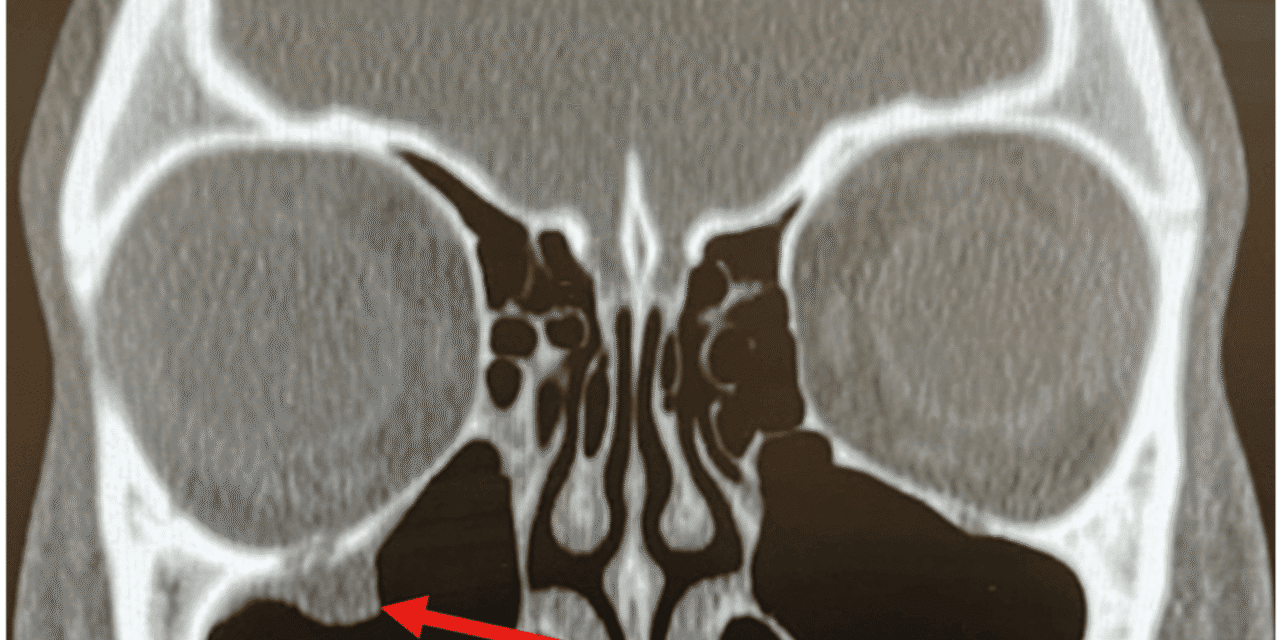

Figure 1. Photos showing normal eye movements of left lateral gaze (left photo), inability of the right eye to elevate (middle photo) and normal right lateral gaze (left photo).

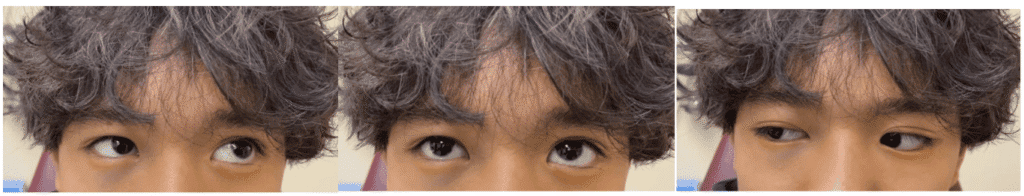

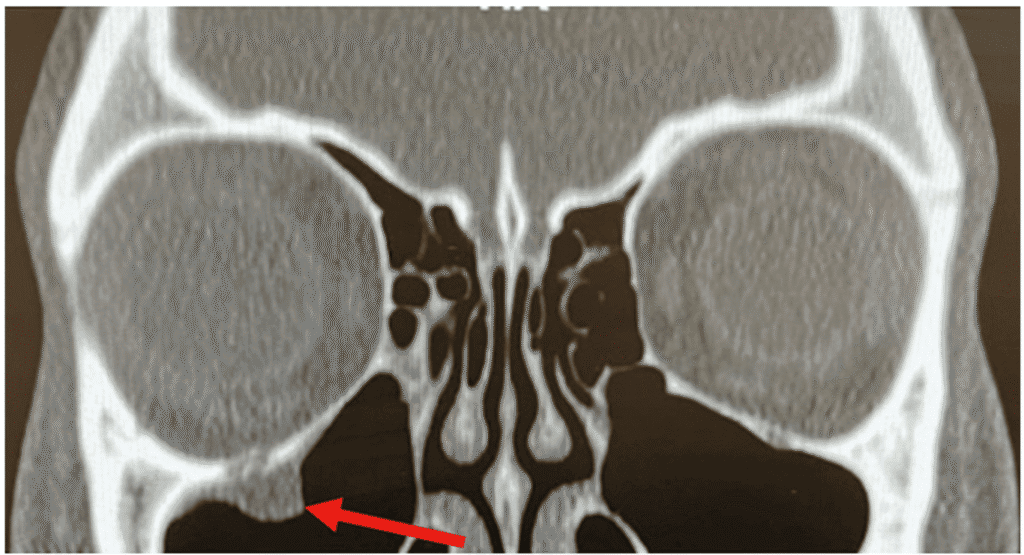

A maxillofacial CT without contrast was ordered. The radiology report revealed a fracture of the right orbital floor with associated orbital soft tissue entrapment in the fracture. The patient was advised to make a follow up appointment in the eye clinic of the hospital the following day. He was also prescribed ibuprofen for pain and advised to use ice packs to control the swelling.

Figure 2. Maxillofacial CT (coronal view, without contrast) showing a right-sided orbital floor trapdoor fracture with associated orbital soft tissue entrapment in the fracture (red arrow).

During the night, the patient’s mother reported hearing a loud crash in the middle of the night and finding her son passed out on the bathroom floor. The child was transported back to the ER via ambulance and reported to have a pulse of 44 at triage. Ophthalmology consultation admitted the patient, and telemetry was consistent with bradycardia that worsened when the child looked up.

The patient was re-evaluated by ophthalmology, oculoplastics and cardiology and deemed to be healthy for emergent surgical correction of the trapdoor fracture and remediation of the oculocardiac reflex. The surgery was uncomplicated and the patient recovered nicely and is currently asymptomatic.

DISCUSSION

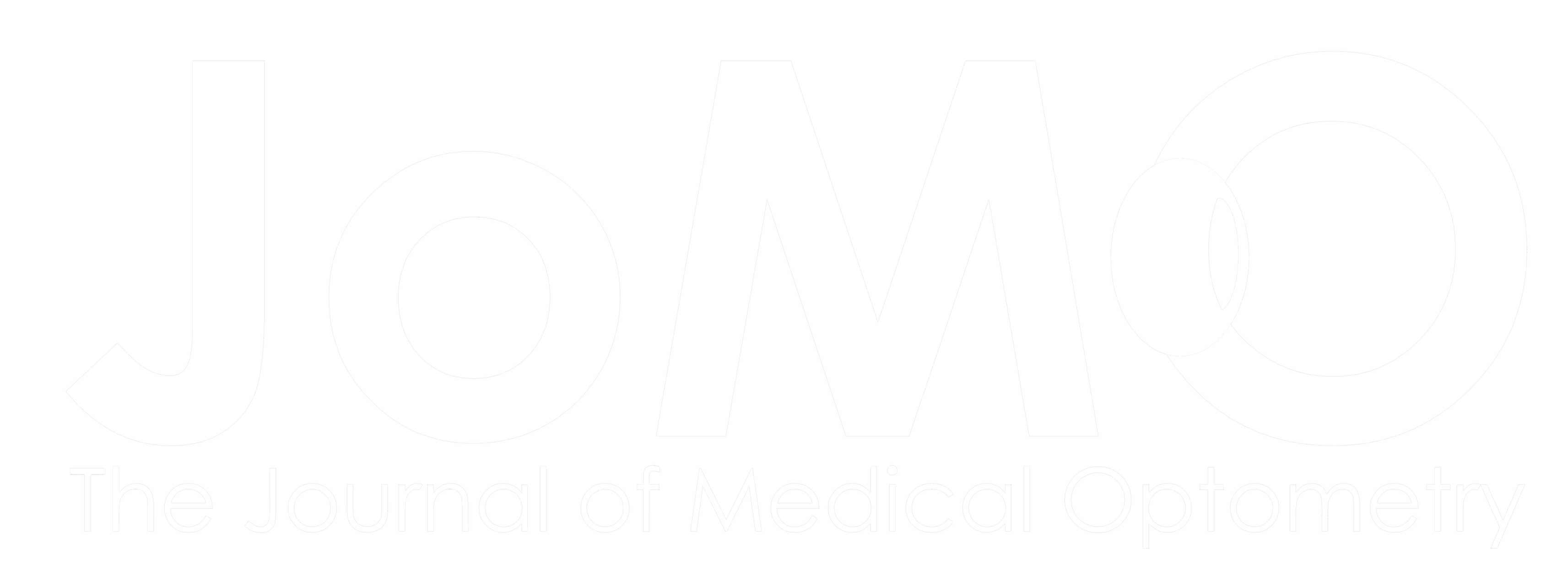

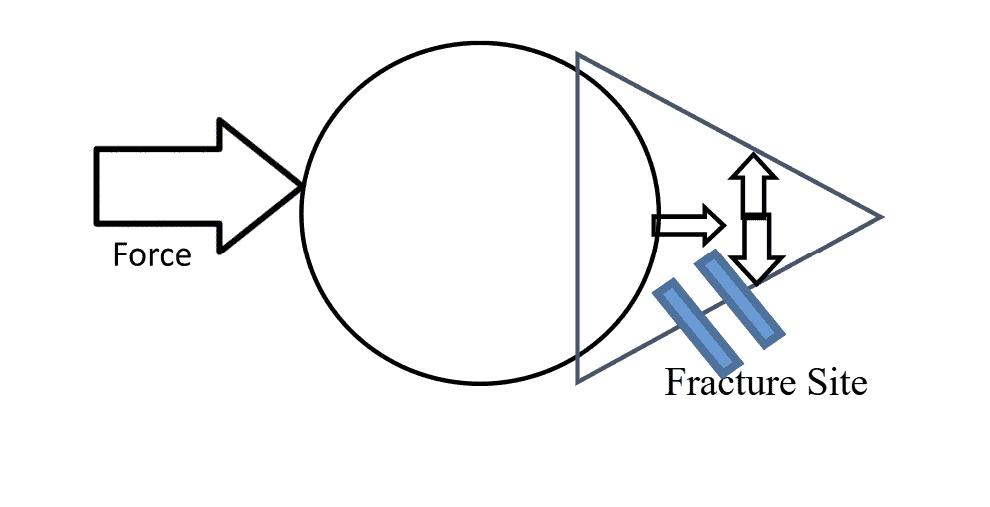

Trap door orbital floor (blowout) fractures come in two types: (1) the linear fracture type and (2) the “swinging door” type. In the linear fracture type, a break occurs in the bones of the orbital floor permitting orbital tissue (the inferior rectus muscle or the inferior periorbital fat) to prolapse into the fracture site. The bony fragments of the fracture then return to their original position, entrapping the prolapsed orbital tissue and creating what is known as the “tear drop” sign. In the hinged fracture type, the fractured part of the floor is minimally displaced acting as the hinge of a “swinging door” entrapping the orbital tissue.6

Orbital trapdoor fractures are most common in children and are defined by the lack of displacement of the involved bones and are a result of acute, transient increase in orbital pressure. However, the mechanism by which orbital fractures occur has been somewhat controversial. The hydraulic theory proposes that retropulsion (backward force) of the globe causes an increase in intraorbital pressure leading to a fracture of orbital bones. A second theory, the buckling theory, states direct trauma to the orbital rim creates force in the posterior direction which creates a compression fracture of the orbital floor.

Figure 3 illustrates the hydraulic theory mechanism of orbital fracture. An outside force causes retropulsion of the globe (large arrow) causing the intraorbital pressure to increase. This increase in pressure is transmitted to all of the walls of the orbit (small arrows) causing the orbital floor to fracture (blue lines). Figure 4 represents the buckling theory. The outside force represented by the large arrow is in the direction of the inferior orbital rim creating the fracture of the orbital floor.

Approximately 29% of patients presenting with an orbital fracture or injury have a concurrent ocular injury as well.7 Blindness associated with orbital fractures has been reported at 0.7%–10%.8,9 Many orbital fracture patients typically complain of periocular swelling and ecchymosis, chemosis, numbness of the cheek (due to V2 involvement), proptosis, enophthalmos and subconjunctival hemorrhage. As in any trauma, a globe rupture must be ruled out immediately as well as an increase in IOP causing an orbital compartment syndrome.

Meticulous assessment of EOMs is imperative in any orbital floor fracture case, especially in a pediatric case. Assessment of extraocular movement is most important in children due to the potential of “trap door fractures” which can be difficult to assess and easily missed. EOM muscle entrapment is more likely to be seen in the pediatric population due to the elasticity of the bones involved. These patients may also present with pain on eye movement, nausea, vomiting, and bradycardia that can mimic the symptoms of a closed head injury. If any orbital floor patient shows signs of nausea, vomiting or bradycardia, activation of the oculocardiac reflex must be assessed with telemetry.

The oculocardicac reflex (also known as the Aschner reflex or trigeminovagal reflex) is a reduction of the heart rate resulting from direct pressure placed on the extraocular muscles, globe, or conjunctiva.10 The reflex is defined by a decrease in heart rate by greater than 20% following the pressure on the EOMs, globe or conjunctiva. The reflex is mediated by the connection between the ophthalmic branch of the trigeminal nerve and the vagus nerve. This potentially life-threatening reflex-induced bradycardia, though it has also been reported to cause arrhythmias and, in extreme cases, cardiac arrest.11 The reflex has most often been encountered during ophthalmologic procedures such as strabismus surgery, though it has also been seen in cases of facial trauma, regional anesthetic nerve blocks, and mechanical stimulation.12

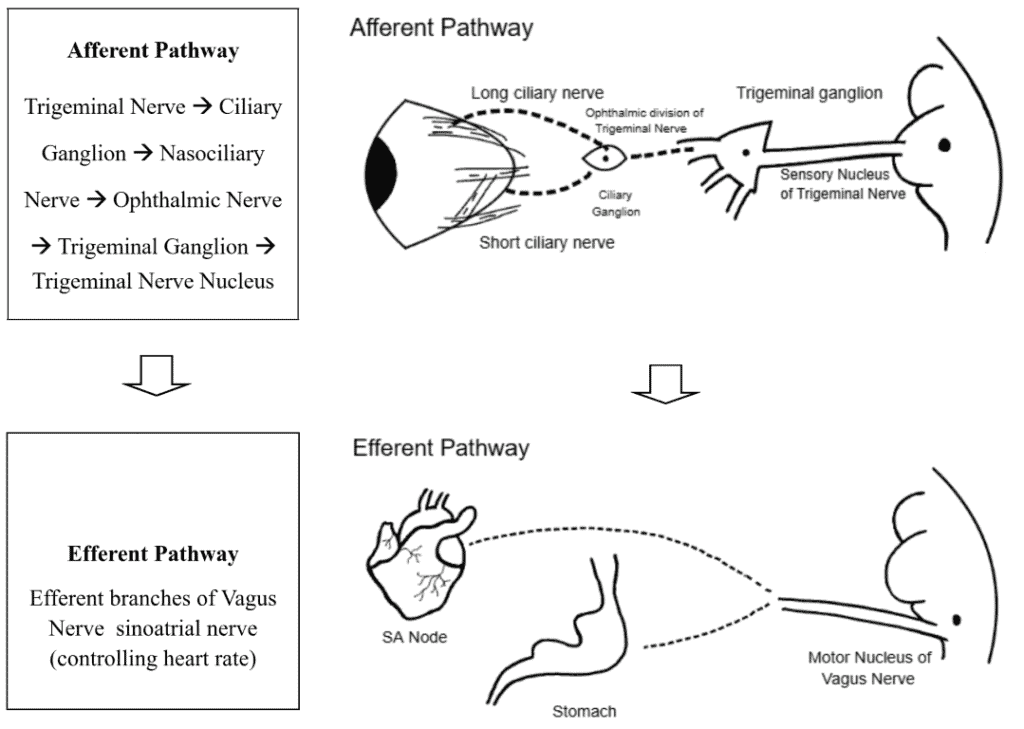

The oculocardiac reflex arc consists of an afferent limb (carried by the trigeminal nerve (CN V) and an efferent limb (carried by the vagus nerve (CN X)). The reflex begins with the activation of stretch receptors in periorbital and ocular tissues. The long and short ciliary nerves carry the impulses to the ciliary ganglion, where the ophthalmic division of CN V carries the impulses to the Gasserian ganglion, and subsequently to the trigeminal nucleus. The afferent nerves synapse with the visceral motor nucleus of the vagus nerve in the reticular formation of the brain stem, where the impulses are then carried to the myocardium to activate the vagal motor response at the sinoatrial (SA) node, resulting in bradycardia.13

Figure 5. Illustration of Both Afferent and Efferent Pathways of Oculocardiac Reflex (Oculocardiac reflex pathway illustration by Abdullah Taher, SUNY

College of Optometry, Class of 2025)

Patients with a history of ocular trauma (particularly orbital fractures) who present with symptoms of an activated OCR need close monitoring with an electrocardiogram (ECG) to assess cardiac function. Not only could this prevent death from fatal arrhythmias induced by the reflex, but it will improve outcomes for ocular motility as well. If heart block is present, immediate surgery is indicated.14 The OCR can be insidious and evolve over time so patients must be well educated on warning signs and symptoms of the OCR activation.15

Pediatric patients with orbital trauma must be carefully evaluated to rule out activation of the oculocardiac reflex. OCR activation does appear to decrease with age, with the pediatric population being most at risk.11 Pediatric patients are not only more likely to be in a situation where the reflex is triggered (i.e., strabismus surgery), but they are also at higher risk of susceptibility to worse outcomes due to their higher dependence on heart rate to maintain cardiac output as compared to adults.16 Although incidence is reportedly higher in younger populations, the reflex occurs in adults and has been seen during many facial trauma surgeries with stimulation of the branches of the trigeminal nerve. 17

Patients with evidence of OCR activation need emergency surgery. Surgery is necessary to release the entrapped tissue and relieve the stimulus. The oculocardiac reflex is commonly encountered with trapdoor-type fractures (as in our patient) where a segment of bone is displaced, and then hinges back to a more normal position, entrapping the orbital tissues. Additionally, current research suggests that early intervention in cases of muscle entrapment resulted in less postoperative diplopia.18

Post-operative recovery of surgically-induced OCR is uneventful if the reflex is recognized and managed appropriately.19 However, there are several reports of OCR-related deaths. It is estimated that 1 out of every 3500 cases of OCR-induced cardiac arrhythmia is fatal, making the quick and accurate diagnosis of OCR important.20 Other reports of death from the OCR have also been reported, resulting from procedures such as cold ocular irrigation, retinal detachment surgery, and strabismus surgery.21

Most orbital floor fractures are treated conservatively through observation: ice packs to decrease swelling, decongestants, prophylactic antibiotics (although this is controversial), pain medications or oral steroids (if edema is impeding proper examination). Patients should be educated to avoid nose blowing to prevent air from entering the orbital cavity and worsening swelling. Nasal sprays can also be used to lubricate the nasal passages and best prevent sneezing.

In cases of large floor fractures (greater than 50% of the orbital floor), persistent diplopia, enophthalmos, muscle entrapment and severe visual impairment, surgical intervention is often indicated. However, in the absence of these symptoms, surgery can often be delayed for a few weeks to allow edema to subside and allow a more accurate assessment of the injury.

Orbital floor fractures (especially in pediatric patients) should be evaluated carefully for OCR activation when an orbital floor fracture is seen or suspected. Symptoms of feeling faint, nausea, lightheadedness or vomiting must be investigated thoroughly. In addition to these symptoms, clinical findings of bradycardia (below 60 beats per minute), hypercapnia, hypoxia, apnea or the use of calcium channel blockers or beta blockers must be considered risk factors for oculocardiac activation as well.

CONCLUSION

Clinical approach to orbital fractures or potential orbital fractures should always include imaging (maxillofacial CT), visual acuity testing, pupil evaluation, extraocular muscle testing, IOP testing and a thorough dilated fundus examination. Many ocular injuries, including orbital trauma, are very often not just isolated to one area of the eye but can often affect several ocular structures concurrently. Therefore, ocular evaluation of the orbital trauma patient should not stop at the orbit solely. Often, a team approach including ER physicians, ophthalmologists, optometrists and other health care specialties can provide the comprehensive care needed to ensure best patient outcomes. Patients and caregivers should be thoroughly educated on warning signs of oculocardiac reflex activation and advised to call emergency services if any symptoms occur.

REFERENCES

- Myers S, Bell D. Orbital blowout fracture from nose blowing. BMJ Case Rep. 2018 Jun 28. 2018.

- Sarbajna T, Valencia MRP, Kakizaki H, Takahashi Y. Orbital Blowout Fracture and Orbital Emphysema caused by Nose Blowing. J Craniofac Surg. 2020 Jan/Feb. 31 (1):e82-e84.

- Waldschmidt B, Gordon N. Anesthesia for pediatric ophthalmologic surgery. J AAPOS. 2019 Jun; 23(3):127-131.

- Dunphy L, Anand P. Paediatric orbital trapdoor fracture misdiagnosed as a head injury: a cautionary tale! BMJ Case Rep. 2019 Apr 03; 12(4).

- Arnold RW, Bond AN, McCall M, Lunoe L. The oculocardiac reflex and depth of anesthesia measured by brain wave. BMC Anesthesiol. 2019 Mar 14; 19(1):36.

- Gerbino G, Roccia F, Bianchi FA, et al. Surgical management of orbital trapdoor fracture in a pediatric population. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2010; 68:1310–1316.

- Kreidl KO, Kim DY, Mansour SE. Prevalence of significant intraocular sequelae in blunt orbital trauma. Am J Emerg Med. 2003;21(7):525–528.

- Ansari MH. Blindness after facial fractures: a 19-year retrospective study. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63(2):229–237.

- Magarakis M, Mundinger GS, Kelamis JA, Dorafshar AH, Bojovic B, Rodriguez ED. Ocular injury, visual impairment, and blindness associated with facial fractures: a systematic literature review. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 2012;129(1):227–233.

- Tobin JR, Grey Weaver R, Chapter 34 – Ophthalmology, A Practice of Anesthesia for Infants and Children (Sixth Edition), Elsevier, 2019, Pages 790-803.e4, ISBN 9780323429740, doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-42974-0.00034-3.

- Dunville LM, Sood G, Kramer J. Oculocardiac Reflex. [Updated 2020 Jun 28]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-.https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK499832/.

- Justice LT, Valley RD, Bailey AG, Hauser MW, CHAPTER 27 – Anesthesia for Ophthalmic Surgery, Smith’s Anesthesia for Infants and Children (Eighth Edition), Mosby, 2011, Pages 870-888, ISBN 9780323066129, doi:10.1016/B978-0-323-06612-9.00027-4.

- Spiriev T, Chowdhury T, Schaller BJ, Chapter 2 – The Trigeminal Nerve: Anatomical Pathways. Trigeminocardiac Reflex Trigger Points, Academic Press, 2015, Pages 9-35, ISBN 9780128004210, doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800421-0.00002-3.

- Sires, Bryan S. M.D., Ph.D. Orbital Trapdoor Fracture and Oculocardiac Reflex, Ophthalmic Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery: July 1999 – Volume 15 – Issue 4 – p 301.

- Yoo JJ, Gishen KE, Thaller SR. The Oculocardiac Reflex: Its Evolution and Management. J Craniofac Surg. 2021 Jan-Feb 01;32(1):e80-e83. doi: 10.1097/SCS.0000000000006995. PMID: 33186288.

- Jean YK, Kam D, Gayer S, Palte HD, Stein ALS. Regional Anesthesia for Pediatric Ophthalmic Surgery: A Review of the Literature. Anesth Analg. 2020;130(5):1351-1363. doi:10.1213/ANE.0000000000004012.

- Pham CM, Couch SM. Oculocardiac reflex elicited by orbital floor fracture and inferior globe displacement. Am J Ophthalmol Case Rep. 2017;6:4-6. Published 2017 Feb 3. doi:10.1016/j.ajoc.2017.01.004.

- Jordan DR, Allen LH, White J, Harvey J, Pashby R, Esmaeli B. Intervention within days for some orbital floor fractures: the white-eyed blowout. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;14(6):379–390.

- Spiriev T, Chowdhury T, Schaller BJ, Chapter 2 – The Trigeminal Nerve: Anatomical Pathways. Trigeminocardiac Reflex Trigger Points, Academic Press, 2015, Pages 9-35, ISBN 9780128004210, doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800421-0.00002-3.

- Sires BS, Stanley RB, Levine LM. Oculocardiac Reflex Caused by Orbital Floor Trapdoor Fracture: An Indication for Urgent Repair. Arch Ophthalmol. 1998;116(7):955–956.

- Smith, R.B. Death and the oculocardiac reflex. Can J Anaesth 41, 760 (1994). Doi: 10.1007/BF03015643.

Dr. Muscente is an optometrist practicing at Richmond University Medical Center and Level 1 Trauma Center. He is a graduate of SUNY College of Optometry in 1994 and completed his residency at the FDR VA Hospital in Montrose, New York. Dr Muscente is an adjunct assistant clinical professor at the SUNY College of Optometry and member of the American Society of Ocular Trauma. Recently, Dr. Muscente co-authored a textbook entitled Complex Cases in Clinical Ophthalmology Practice and lectures extensively on topics related to ocular emergencies and trauma. He thoroughly enjoys working with optometry students and currently resides in New Jersey.