Bilateral Optic Nerve Edema Leading to the Diagnosis of Ocular Syphilis

ABSTRACT

INTRODUCTION

Ocular syphilis has broad, nonspecific signs and symptoms caused by infection with Treponema pallidum bacterium. Periods of active and latent infection occur, which often delays diagnosis. While syphilis remains a common differential diagnosis for many ocular conditions, a thorough workup must be completed including case history of prevalent risk factors, lab serology, and cerebral spinal fluid analysis. Syphilis may infect the anterior and posterior segments of the eye but most often presents as panuveitis or posterior uveitis. Other common ocular findings include optic nerve edema, interstitial keratitis, and retinal vasculitis. The gold standard treatment remains intramuscular or intravenous penicillin.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old Caucasian male presented with loss of vision related to bilateral optic nerve edema with serological confirmation of syphilis and concurrent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Extensive lab testing and imaging were conducted, confirming the diagnosis of syphilis and HIV. Interdisciplinary care was coordinated and treatment was initiated for both infections.

CONCLUSION

This case emphasizes the importance of testing for syphilis in cases of optic nerve edema and testing for concurrent HIV infection. Due to the systemic nature of this infection, interdisciplinary care is crucial to prevent serious complications.

Keywords: Syphilis, ocular syphilis, neurosyphilis, optic nerve edema

INTRODUCTION

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum, a gram-negative spirochete bacterium. It is primarily a sexually transmitted infection passed through unprotected sex, allowing the bacteria to enter mucosal membranes, leading to infection.1 Other methods of spread include vertical transmission occurring during pregnancy and blood transfusions. The incubation period of syphilis is three to four weeks.1 Between 1990 and 2019, there was a 60% increase in the prevalence of syphilis cases globally, leading to its classification as a public health crisis.1,2 Major risk factors of contracting syphilis are unprotected sex, drug abuse, men who have sex with men (rate of infection 15 to 20 times greater), and infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).2 Syphilis infection is most commonly found in men who are between 20-29 years old. Due to the various presentations of the infection and nonspecific signs, syphilis is known as a “great masquerader.” The signs and symptoms may range from asymptomatic to severe, and it can affect multiple organ systems. Common ocular nerve findings of syphilis include papilledema, optic neuropathy, optic neuritis, papillitis, optic perineuritis and neuroretinitis.3

To confirm the diagnosis of syphilis, blood work must be completed, including both nontreponemal and treponemal screening. In cases with a positive result, it is recommended to also test for HIV due to co-infection rates. Treatment of syphilis and neurosyphilis with antibiotics is crucial due to the possible terminal effects.

CASE REPORT

A 40-year-old Caucasian male presented to the urgent eye care clinic following an emergency room visit, reporting painless loss of vision in the left eye that started four days prior. The patient denied headaches, nausea, or vomiting but was experiencing dizziness. The patient denied flashes, floaters, or curtain veil effect in vision. His ocular history consisted of a prior corneal ulcer OD, which had since resolved. Medical history included alcohol dependence, depression, anxiety, chronic post-traumatic stress disorder, and hyperlipidemia. He reported taking atorvastatin calcium 80 mg tab PO QHS. The patient reported no known medical allergies. The patient’s family ocular history was unremarkable. The patient reported occasional use of artificial tears.

Best-corrected visual acuity OD was 20/20 and uncorrected visual acuity OS was hand motion at two feet without improvement on pinhole. Pupils were equal, round, and reactive to light with no afferent pupillary defect (APD) noted. Extraocular motility exhibited a full range of motion. Confrontation visual fields were full to finger counting OD and OS. Intraocular pressure was measured as 17 mmHg OD and OS.

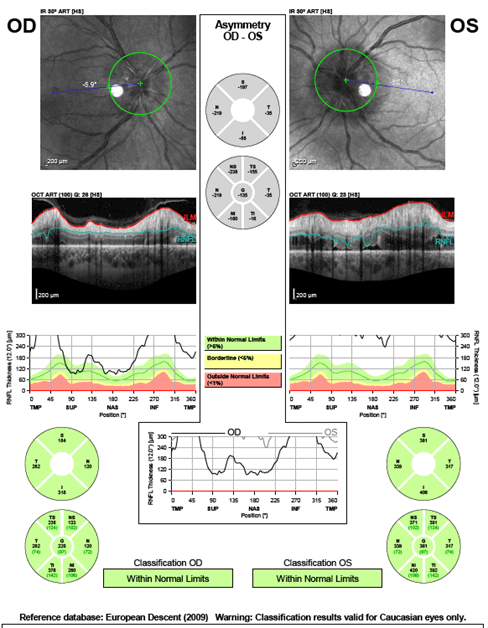

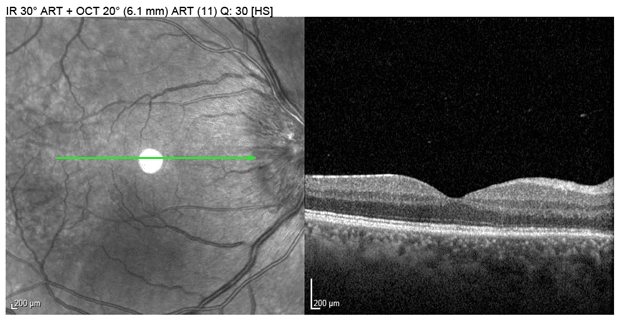

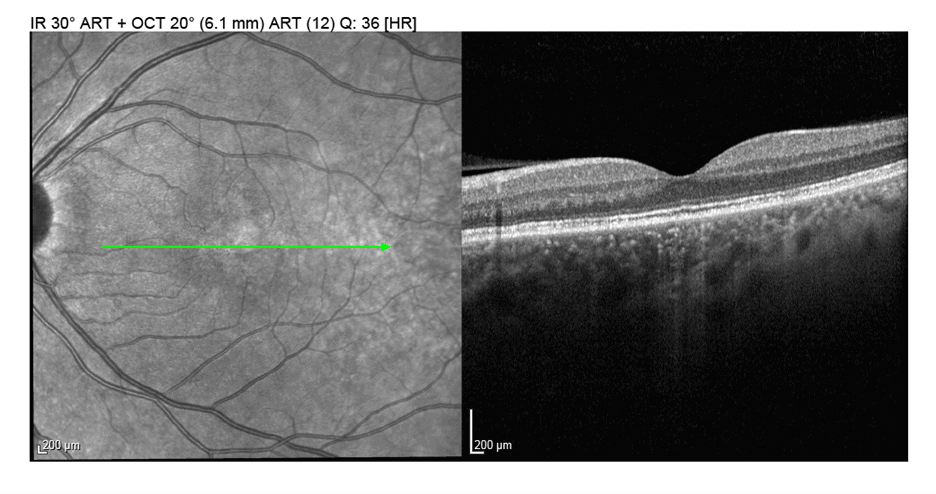

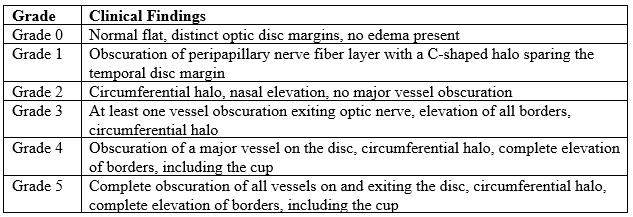

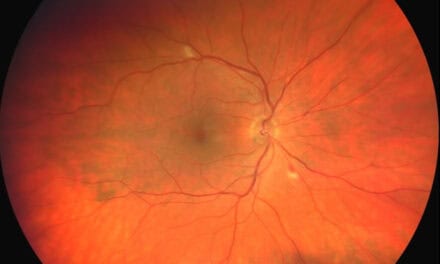

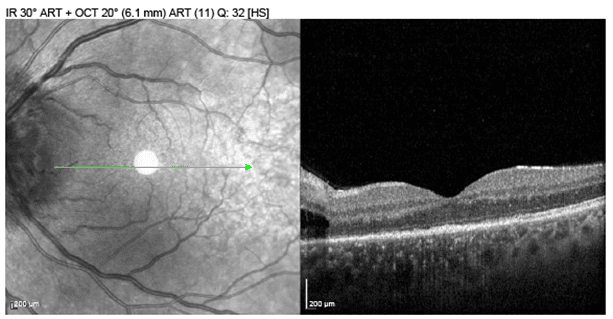

Anterior segment examination was within normal limits for both eyes. No madarosis, blepharitis or maculopapular rash was noted on the eyelids OU. All layers of each cornea were clear with no signs of interstitial keratitis. No cells or flare were noted in the anterior chamber of either eye. Posterior segment evaluation revealed optic nerve edema with blurred margins and hyperemia in both eyes, Frisen grade 2 OD and grade 3 OS. Peripapillary intraretinal fluid was noted OS on optical coherence tomography (OCT). The macula was flat and clear in both eyes. No cells were present in the vitreous OD or OS. Retinal blood vessels had a 2/3 ratio with no vasculitis of either eye. No retinal holes, tears, or detachments were detected in the periphery OU.

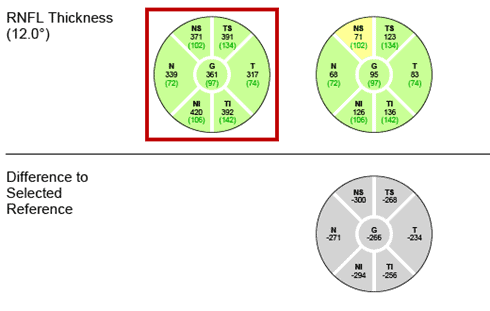

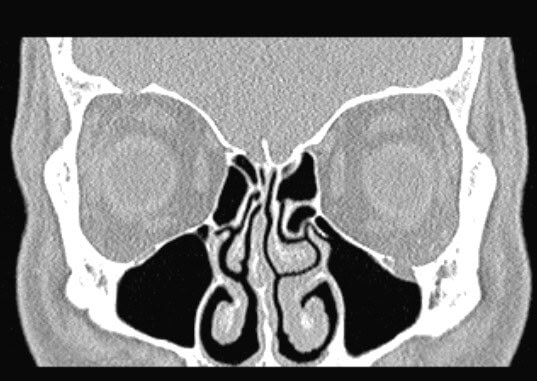

Optical coherence tomography (Figure 1) was performed, confirming the presence of optic nerve edema, displaying an increased thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer of both eyes. Disc swelling was also visible in the infrared OCT images (Figures 2 and 3). There was intraretinal edema present extending from the temporal left optic nerve head toward the macula (Figure 3). A CT scan without contrast of the orbit and head were ordered the same day to rule out a compressive etiology (Figure 4). Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was unable to be performed due to lack of equipment on site.

Non-contrast head CT report was read as: “No definite CT evidence of acute major cortical-based infarct, intracranial hemorrhage, mass or midline shift. Old left lateral orbital floor fracture, with focal inferior herniation of the left intraorbital fat and mild relative fullness of the belly of the left inferior rectus muscle, which however is not pathologically enlarged. Old mildly displaced left nasal bone fracture. Prominent bilateral posterolateral and superior nasopharyngeal soft tissues likely represent reactive lymphoid hypertrophy.”

Figure 4. CT without contrast of the head depicting left lateral orbital floor fracture with focal inferior herniation of the left intraorbital fat. Orbits and optic nerves were otherwise normal bilaterally.

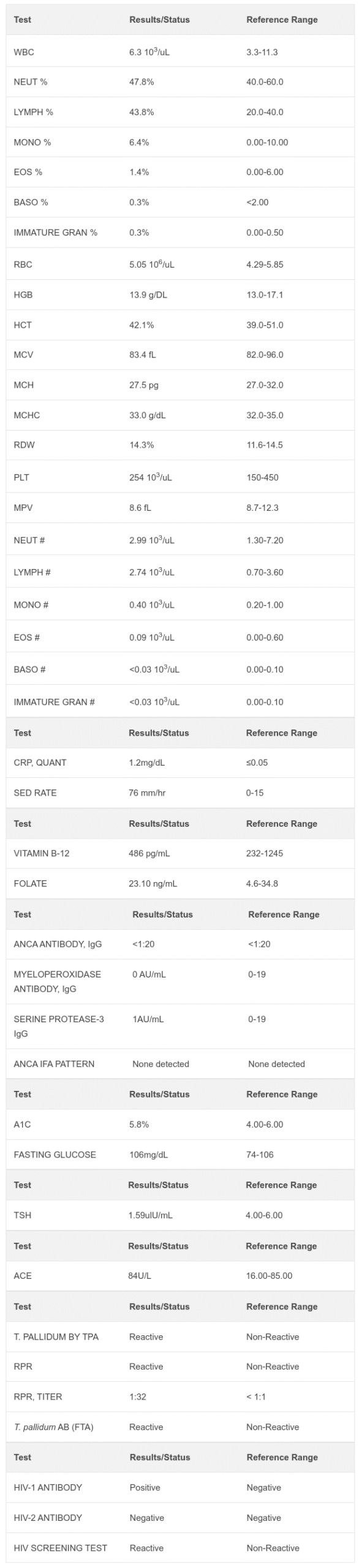

Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS), rapid plasma reagin (RPR), and HIV positive serology results identified the infectious etiology of this patient’s optic nerve edema, leading to a diagnosis of secondary syphilis with concurrent HIV infection. There was an increased lymphocyte percentage due to the presence of the co-infections. Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and C-reactive protein (CRP) were elevated, demonstrating nonspecific, active inflammation. The local health department was notified of the diagnosis. The CT scan and lab results were discussed with the patient, and the patient’s primary care provider was notified of the diagnosis for assistance with treatment coordination. The patient was advised of the severity of the condition and the importance of initiating treatment for syphilis and HIV.

FOLLOW-UP

Interdisciplinary coordinated care was organized and scheduled with infectious disease specialists, primary care physicians and optometry. The patient was to receive intravenous penicillin from infectious disease specialists and a lumbar puncture to evaluate cerebral spinal fluid composition and opening pressure. The patient declined a lumbar puncture, so the diagnosis of neurosyphilis could not be confirmed. The patient completed a treatment of continuous intravenous penicillin G potassium 20 million unit solution IV over the span of 24 hours for the duration of one week through home care. He did not complete the full treatment that was recommended by infectious disease specialists. The patient’s primary care physician prescribed Biktarvy 20/200/25 tab PO once daily. The patient did not return for his one-week follow-up with the optometry clinic but reported to his primary care provider that his vision had improved since his syphilis treatment.

The patient presented to the optometry clinic nine months later for a follow-up on his bilateral optic nerve edema and reported that vision had improved OU two days after initiating the IV penicillin treatment. He reported that he did not fully complete the IV penicillin treatment but is currently compliant with his Biktarvy 20/200/25 tab PO once daily. The concurrent HIV infection is managed by primary care.

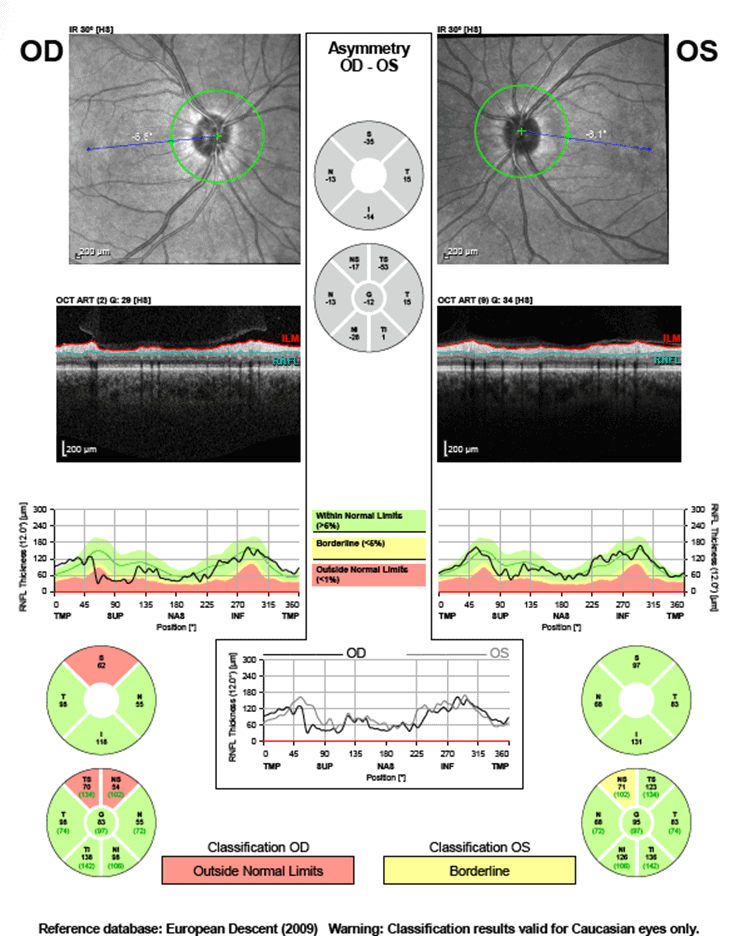

Best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye. Entrance tests were normal and anterior segment examination was within normal limits for both eyes. Posterior segment evaluation revealed flat and clear optic nerve margins with no signs of edema OU. Optical coherence tomography (Figure 5) showed the resolution of optic nerve edema with a decreased thickness of the retinal nerve fiber layer of both eyes compared to the initial visit. Retinal nerve fiber layer thinning was noted OD and borderline thinning OS was present. Progression analysis displayed improvement of edema OU (Figures 6 and 7) The peripapillary intraretinal edema OS had resolved (Figure 8).

Figure 5. OCT imaging confirming resolution of optic nerve edema OU, and demonstrating resultant superonasal and superotemporal thinning noted OD and borderline thinning superonasal OS.

The patient was educated on the resolution of the optic nerve edema OU and was again told of the importance of completing the full treatment for syphilis. The patient agreed to seek further care for continuation of syphilis treatment and will continue HIV care with his primary care providers. Care was coordinated with infectious disease specialists to re-establish syphilis management.

DISCUSSION

Treponema pallidum leads to a diverse array of clinical presentations, highlighting the difficulty of making a timely and accurate diagnosis. Patients may present with ocular manifestations during any stage of syphilis. Primary syphilis occurs when a single chancre or multiple lesions are present about three weeks after exposure to the bacterium.3 Typical lesions resolve without treatment after 4-6 weeks. Ocular syphilis occurs when T. pallidum is transferred from the infection site to the eye. This transfer of bacteria leads to primary syphilis, which is commonly classified as chancres of the eyelid and conjunctiva.5

According to Peeling et al, “Resolution of primary lesions is followed 6–8 weeks later by secondary manifestations, which can include fever, headache and a maculopapular rash on the flank, shoulders, arm, chest or back and that often involves the palms of the hands and soles of the feet.” The maculopapular rash is highly contagious and, if present on the eyelids, may cause blepharitis and madarosis.4,5 The most common ocular findings of secondary syphilis include panuveitis and posterior uveitis.5 Other ocular findings include anterior uveitis, vitritis, episcleritis, necrotizing retinitis, scleritis, keratitis, retinal vasculitis, and retinal detachment.5,7

Latent syphilis occurs when the clinical manifestations of secondary syphilis resolve, and patients enter a stage where no signs or symptoms are present. There are no ocular findings of latent syphilis and 33% of these patients will progress to tertiary syphilis.1

Neurosyphilis comprises several stages. Neurosyphilis is classified as the presence of T. pallidum in the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) that may occur within hours of infection and is due to an inflammatory response resulting in nerve cell damage or death. The majority of patients will have clearance of the bacteria from the CSF, thus presenting with no clinical symptoms of neurosyphilis.2 Neurosyphilis classification is further broken down into early, intermediate, and late stages. The initial early stage is asymptomatic neurosyphilis, consisting of no neurological symptoms while having a positive Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL).2 Meningeal neurosyphilis is classified as part of the early secondary stage, and occurs within a year of infection but may take years for symptoms to present. This stage is due to meningeal inflammation leading to cranial nerve abnormalities, headache, confusion, photophobia, nausea, vomiting, facial ptosis, neck stiffness, papilledema, and seizures.2 Meningovascular neurosyphilis is the next stage, which is similar to meningeal neurosyphilis but includes endarteritis, which increases a patient’s likelihood of having a stroke or other cerebrovascular pathology and occurs after 5-12 years.2 Late-stage neurosyphilis has several substages including syphilitic paresis and syphilitic myelitis, which occur over 10 years after initial infection. Syphilitic paresis presents with cognitive issues such as dementia, personality changes, hallucinations, or psychiatric disorders due to the chronic inflammation and atrophy of the brain. Late manifestations of syphilitic paresis involve tremors, seizures, abnormal reflexes, and jerking. Syphilitic myelitis occurs 20-25 years after infection and is the result of chronic inflammation destroying the posterior dorsal columns and dorsal nerve roots, causing demyelination.2,7,8 This stage is also known as tabes dorsalis and manifests with a charcot spine which is vertebral joint degeneration that can lead to an unbalanced gait, sharp pain, reduced reflexes, loss of proprioception, and visceral crisis.2,8 Other ocular findings of neurosyphilis include uveitis, eyelid gummas, vitritis, chorioretinitis, optic neuritis, optic atrophy, papillitis, interstitial keratitis, scleritis, optic nerve edema, and vasculitis.7,8 Symptoms include loss of vision, blurry vision, floaters, flashes, eye pain, and photophobia.1

Tertiary syphilis involves cardiovascular, neurological, bony involvement, or severe skin lesions also known as gummas after 15-30 years.4 Common findings include endarteritis, aortic valvulopathy, gummas of variable organ systems leading to their destruction, and various neurological symptoms. Tertiary and neurosyphilis can easily be misconstrued as the same, but they are clinically different. Tertiary syphilis can involve non-neurological organ systems, while neurosyphilis is only accurate in cases of neurological involvement and T. pallidum in the CSF during any time of the syphilitic infection.

Argyll-Robertson pupils are a highly specific sign of tertiary syphilis and neurosyphilis, which are classified as bilateral pinpoint pupils with an intact near response but diminished light reactivity due to damage to the pretectal nuclei.2,7

Optic nerve involvement may present unilaterally or bilaterally. It may be associated with optic nerve edema, papilledema, acute placoid chorioretinitis, optic neuritis, papillitis, and/or perineuritis.6,9 Optic nerve edema may be present without ocular inflammation, perineuritis or increased CSF pressure. The bacteria can infect the meningeal sheath of the optic nerve causing perineuritis.10 Anterior optic neuritis due to syphilis presents with an inflamed posterior vitreous and inflamed optic nerve.9 Posterior optic neuritis will not present with clinically visible inflammation of the optic nerve but rather with a relative afferent pupillary defect and dyschromatopsia.9 An ischemic mechanism of optic nerve edema occurs when vasculitis of the posterior ciliary arteries results in thrombosis, occlusion, and infiltration leading to arterial narrowing causing subsequent ischemic infarction.10 Optic nerve edema is graded using the Frisén scale.

The diagnosis of syphilis consists of a combination of serology and CSF analysis to evaluate for neurosyphilis. In general, syphilis is commonly undiagnosed as a result of unrecognized nonspecific symptoms. One method of diagnosis is through serological testing which includes nontreponemal screening: VDRL, Toluidine Red Unheated Serum Test (TRUST), and RPR. These tests are used to detect IgG and IgM antibodies that are released during syphilis infection, detecting an active infection.1,3,12,13 Treponemal antibody testing includes FTA-ABS, T. pallidum particulate agglutination (TP-PA), enzyme immunoassays (EIA) and chemiluminescence immunoassays.13 Unlike nontreponemal assays, treponemal assays are unable to distinguish between active or past infections but test for syphilitic antigens.14 Another method of evaluation is darkfield microscopy examination which encompasses the microscopic examination of active infection but is no longer frequently used.1 Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays provide high specificity and sensitivity while evaluating serum, CSF, and tissue samples.1 It has become routine to screen patients with a positive syphilis test for HIV due to the overlap of risk factors between the infections.1 Human immunodeficiency virus is a retrovirus and if untreated, will cause acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), defined by a cluster of differentiation 4 (CD4) cell count of less than 200/microliters.14 The CDC reports that men who have sex with men comprise 80% of all cases of syphilis and 47% of those cases also have HIV.1

According to the CDC guidelines, primary, secondary, early latent syphilis, or concurrent HIV infections are treated with a single dose of benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units intramuscularly (IM).15 If a penicillin allergy is present, 100 mg of doxycycline twice a day for 14 days or 500 mg of tetracycline four times a day for 14 days is recommended. Tertiary and late latent syphilis are treated with benzathine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM once a week, for three weeks. Late latent patients with HIV are treated similarly to late latent patients without HIV infection and if patients are allergic to penicillin, 100 mg doxycycline twice a day or 500 mg tetracycline four times a day for 28 days is recommended. For patients with neurosyphilis, ocular syphilis, and otosyphilis, aqueous crystalline penicillin G is required in 3-4 million units (intravenously) IV, every 4 hours for 10-14 days.15 An alternative treatment for these patients is a single dose procaine penicillin G 2.4 million units IM with probenecid 500 mg orally four times daily for 10-14 days. If a patient in this category has a penicillin allergy, there is an alternative treatment option of ceftriaxone 1-2g daily IM or IV for 10-14 days, but this treatment has not been greatly studied. Untreated syphilis may be fatal due to end-organ damage of multiple systems, and prognosis depends upon several factors including the stage of infection and which organs are infected.

CONCLUSION

This case emphasizes the importance of conducting a thorough case history, evaluating pertinent risk factors, observing clinical findings, performing proper serology, and assessing CSF when bilateral optic nerve edema is present. It is critical to consider syphilis in the differential diagnosis of patients with optic nerve edema due to its various clinical presentations, highlighting the complexity of this infection. This case also emphasizes the significance of HIV testing when a patient tests positive for syphilis due to the high rate of concurrent infection. Patients who have syphilis and HIV should notify their sexual partners about their diagnosis and advise them to be tested as well. Treatment requires a multidisciplinary approach due to the complexity and wide array of infection with multiple organ involvement. Early intervention is crucial to provide patients with optimal outcomes. Educating patients on the risk factors of syphilis and the possible detrimental outcome of this condition if left untreated is important to ensure compliance with treatment and follow-up care.

REFERENCES

- Tudor ME, Al Aboud AM, Leslie SW, et al. Syphilis. [Updated 2024 Aug 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534780/

- Ha T, Tadi P, Leslie SW, et al. Neurosyphilis. [Updated 2024 Apr 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK540979/

- Peeling RW, Mabey D, Kamb ML, Chen XS, Radolf JD, Benzaken AS. Syphilis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17073. Published 2017 Oct 12. doi:10.1038/nrdp.2017.73

- Nyatsanza F, Tipple C. Syphilis: presentations in general medicine. Clin Med (Lond). 2016;16(2):184-188. doi:10.7861/clinmedicine.16-2-184

- Koundanya VV, Tripathy K. Syphilis Ocular Manifestations. [Updated 2023 Aug 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK558957/

- Kabanovski, Anna BHSc; Donaldson, Laura MD; Jeeva-Patel, Trishal MD; Margolin, Edward A. MD. Optic Disc Edema in Syphilis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology 42(1):p e173-e180, March 2022. | DOI: 10.1097/WNO.0000000000001302

- Diagnosis and Management of Ocular Syphilis. American Academy of Ophthalmology. Published May 1, 2023. https://www.aao.org/eyenet/article/diagnosis-and-management-of-ocular-syphilis

- Matthew M Hamill, Khalil G Ghanem, Susan Tuddenham, State-of-the-Art Review: Neurosyphilis, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 78, Issue 5, 15 May 2024, Pages e57–e68, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/ciad437

- Ophthalmologic Manifestations of Syphilis – EyeWiki. eyewiki.org. https://eyewiki.org/Ophthalmologic_Manifestations_of_Syphilis

- Kabanovski A, Donaldson L, Jeeva-Patel T, Margolin EA. Optic Disc Edema in Syphilis. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2021;42(1):e173-e180. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/wno.0000000000001302

- Papilledema – EyeWiki. Eyewiki.org. Published December 19, 2023. https://eyewiki.org/Papilledema#Physical_examination

- Goza M, Kulwicki B, Akers JM, Klepser ME. Syphilis Screening: A Review of the Syphilis Health Check Rapid Immunochromatographic Test. J Pharm Technol. 2017;33(2):53-59. doi:10.1177/8755122517691308

- Zhou J, Zhang H, Tang K, Liu R, Li J. An Updated Review of Recent Advances in Neurosyphilis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:800383. Published 2022 Sep 20. doi:10.3389/fmed.2022.800383

- Feroze KB, Gulick PG. HIV Retinopathy. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470530/

- CDC. Syphilis – STI treatment guidelines. www.cdc.gov. Published 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment-guidelines/syphilis.htm