Anemic Retinopathy Secondary to Babesiosis Infection

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Babesiosis is a tickborne disease caused by protozoa that infect and lyse red blood cells. In 2023, the CDC declared Babesiosis endemic in the states of Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire due to the increased incidence of infection over the past decade. This report describes a rare case of Babesiosis and its ocular manifestations.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old male presented for an eye examination while hospitalized with Babesiosis infection and secondary autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Fundus examination demonstrated moderate retinal ischemia presenting as scattered cotton wool spots and retinal hemorrhages concentrated bilaterally in the posterior pole. An extended period of antibiotic and steroid treatment was required to clear the infection and normalize blood levels, while the retinopathy took several additional months to completely resolve.

CONCLUSION

This case demonstrates how Babesiosis can lead to anemic retinopathy. Babesiosis should be considered when retinopathy is encountered, particularly in individuals with known tick exposure.

Keywords: Babesiosis, retinopathy, hemolytic anemia

INTRODUCTION

Approximately 50,000 Americans are infected with tickborne diseases yearly.1,2 Babesiosis, also referred to as “Nantucket fever,” accounts for approximately 2,000 cases. Despite the relatively low number of infections, the incidence of Babesiosis has significantly increased. Cases have jumped 17-fold in Vermont, 15-fold in Maine, and 6-fold in New Hampshire over the past decade; consequently, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) declared Babesiosis endemic in those three states in 2023.3,4

Babesiosis infects and kills erythrocytes leading to symptoms in 75% of infected adults and 50% of infected children.5 The course of infection can range from asymptomatic to life-threatening. Symptoms may include chills, sweats, myalgias, headache and nausea. Serious complications are common and include severe anemia, renal insufficiency, pulmonary failure, and heart failure. Babesiosis can also trigger an autoimmune form of hemolytic anemia, where host red blood cells are mistaken for foreign substances and attacked by the host immune system.6

Babesiosis infection is typically treated with oral or intravenous azithromycin and oral atovaquone, while autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA) is managed with steroids and other immunomodulators. Both Babesiosis infection and secondary AIHA require prompt care and can be fatal if left untreated.5,6

Reported ocular manifestations of Babesiosis infection include optic neuritis, retinal hemorrhages, and nerve fiber layer infarcts.7-9 However, the literature regarding the ocular complications of Babesiosis infection is sparse. Herein a rare case of retinal ischemia due to Babesiosis infection and secondary autoimmune hemolytic anemia is described. The patient in this report experienced resolution of his systemic condition after approximately ten weeks of antibiotic and steroid therapy. The retinopathy was slower to resolve, taking nearly one year to completely clear.

CASE REPORT

A 73-year-old Caucasian male hospitalized with Babesiosis and secondary AIHA following a tick bite presented for an inpatient eye consultation. The patient had complaints of constant, mild blur at distance in both eyes which preceded the onset of his hospitalization. Ocular history was significant for cataract extraction in both eyes, mild dry eye, and a longstanding peripheral retinal cavernous hemangioma in the left eye.

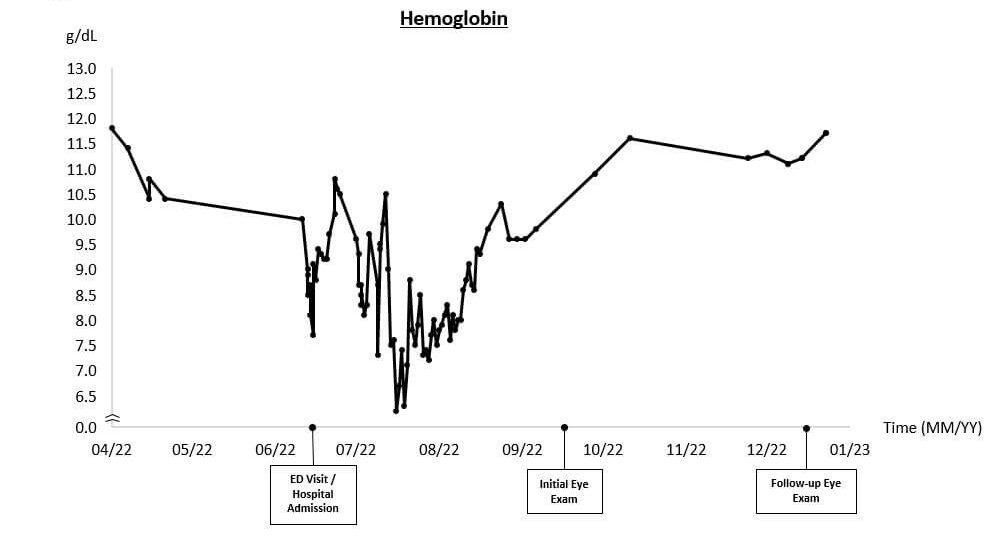

In the lead up to his eye exam, infection with Babesia microti and secondary AIHA had caused the patient’s hemoglobin (Hgb) to reach critically low levels (Figure 1, Hgb = 6.2 g/dL, normal range: 12.8-17 g/dL). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing and peripheral blood smear had been used to detect an acute Babesiosis infection, while autoimmune hemolytic anemia was diagnosed based on elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), low haptoglobin, and a positive direct auto-antiglobulin test (DAT).

The patient’s other medical history included hypertension (controlled with carvedilol), hypothyroidism (treated with levothyroxine), obstructive sleep apnea, peripheral venous insufficiency, allergic rhinitis (treated with fluticasone), osteoporosis, degenerative joint disease, vitamin D deficiency (treated with vitamin D3), and esophageal cancer successfully treated with radiation and chemotherapy.

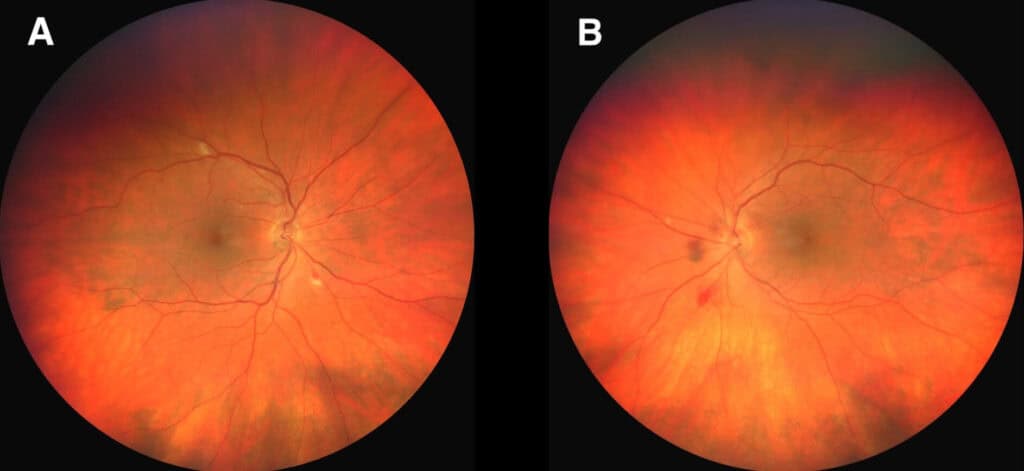

Upon eye examination, best-corrected vision was 20/20 in each eye with a slightly hyperopic distance correction. Entrance testing and anterior segment findings were unremarkable. Intraocular pressures were 10 mmHg and 9 mmHg in the right and left eye, respectively. The posterior segment evaluation revealed scattered cotton wool spots and a combination of flame-shaped and large dot-blot hemorrhages in both eyes (Figure 2). A Roth spot was noted in the left eye. Macula OCT was remarkable for vitreomacular adhesion in the right eye and drusen bilaterally.

A diagnosis of anemic retinopathy with ischemia secondary to Babesiosis infection with AIHA was made. Due to the absence of sight-threatening eye disease and the improvement in hemoglobin levels leading up to the eye exam, a follow-up was planned for three months.

Shortly after his eye exam, the patient was discharged after a ten-week hospitalization, where continuous systemic steroids (dexamethasone followed by oral prednisone), antimicrobial treatment consisting of atovaquone and azithromycin, and several blood transfusions were used to clear the infection and improve his anemia.

Over the next three months, the patient’s anemia continued to subside. At the follow-up eye exam, the patient reported no visual symptoms, and the retinal ischemia had significantly improved; the cotton wool spots had resolved, and only a few retinal hemorrhages were present in the midperipheral retina bilaterally. The patient was evaluated again at six and nine months after discharge with continued improvement in the clinical findings, as only a few small hemorrhages were found peripherally in both eyes. After one year, the retinopathy had completely resolved.

DISCUSSION

Babesiosis is an emerging infectious disease caused by protozoan in the genus Babesia. Over 100 Babesia species have been identified, but few infect humans. In the United States, B. microti is the most prevalent infectious species, with the majority of cases reported in the Northeast and upper Midwest regions of the country during the spring and summer months.5,6

The vector for nearly all Babesia species is the Ioxid tick (deer tick), the same vector that carries the bacteria that cause Lyme disease, Borrelia burgdorferi.10,11 When a tick carrying Babesia attaches to a human host, Babesia sporozoites are transmitted into the host’s bloodstream. Babesia sporozoites enter erythrocytes, undergo rapid replication, lyse the host cell, and successively infect other erythrocytes, leading to disease.10

Symptoms of Babesiosis infection usually develop one to four weeks after exposure. Fever, chills, sweats, malaise, headache, myalgia, and nausea are common in mild cases.5 In severe disease, symptoms are more intense, and additional life-threatening complications may develop. These include hemolytic anemia, congestive heart failure, renal and liver impairment, and acute respiratory distress syndrome.5,6 The course of infection depends on the Babesia species and the immune status of the host.5,6 Risk factors for severe infection include immunosuppression, cancer, hyposplenism, and advanced age.6,12

Babesia should be considered in any symptomatic patient who presents with a history of a tick bite in an endemic region. Lab evaluation following a tick bite should also investigate for other tick-borne illnesses, including Lyme disease, anaplasmosis, and ehrlichiosis.13 Acute Babesiosis infections are diagnosed by peripheral blood smear and PCR analysis, while specific serum antibodies become detectable several weeks after exposure.6,14

Anemia is a frequent finding in Babesiosis.5,15 Anemia is clinically defined as blood hemoglobin (Hgb) < 12 g/dL in females and < 13 g/dL in males. The primary function of Hgb is oxygen delivery from the lungs to the body tissues. As the oxygen transport capacity of blood decreases, tissue functions are impaired and symptoms of anemia become visible. Symptoms include pale skin, general body weakness, tiredness, dizziness, breathlessness, and cardiac issues like tachycardia.16 Severity of symptoms depends on the Hgb level, the rate of decline, and other comorbidities. Most adults will become symptomatic when Hgb declines to 8 to 9 g/dL although acute hemolytic anemia can cause severe symptoms even in relatively mild drops in Hgb.17,18

Anemia represents one of the most common abnormalities encountered in lab testing. It is the result of decreased production, increased loss, or premature destruction of red blood cells. The anemia in Babesiosis is hemolytic, where red blood cells are either destroyed directly by Babesia sporozoites, or, less commonly, due to an autoimmune response triggered by the infection, known as autoimmune hemolytic anemia (AIHA).15,17

Hemolytic anemia can be immune or non-immune. It is diagnosed through lab testing and microbiology. Findings include increased bilirubin, lactose dehydrogenase, and plasma-free hemoglobin. Decreased haptoglobin, reticulocytosis, and abnormalities on the peripheral blood smear are also common. To distinguish immune from non-immune subtypes, direct antiglobulin testing (DAT; formerly Coombs testing) is used. AIHA is characterized by the presence of auto-antibodies or complement proteins detectable on DAT.17,18

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia develops in up to seven percent of Babesiosis cases shortly after antimicrobial treatment is initiated.6,14 Risk factors for AIHA include advanced age, comorbid autoimmune disease, asplenia, sickle cell disease, and malignancy.16,17 AIHA should be considered in patients with worsening or recurrent hemolytic anemia after treatment of Babesiosis.15

Literature describing the effects of Babesiosis on the eye is limited. In previous case reports, infection complicated by anemia resulted in retinal hemorrhages, nerve fiber layer infarcts, and mild optic neuritis, all of which resolved after treatment.8,9 In contrast, a recently published study of 10 patients with Babesiosis found none had retinopathy, leading the authors to conclude the infection has low potential to cause retinal disease.19 However, in that small study, the ocular examinations were limited to bedside indirect ophthalmoscopy, and no information regarding anemic status was provided. In this case, Babesiosis led to severe anemia, which most likely factored into the ocular findings. With the number of cases on the rise, more information regarding potential ocular complications in Babesiosis is likely to emerge.

The prevalence of retinopathy in anemia has been reported to be between 20–30%.20-22 The likelihood of retinopathy increases as the severity of anemia worsens, especially when Hgb levels drop below 10 gm/dl.23,24 Retinopathy has been reported in all types of anemia, including iron deficiency, aplastic, sickle cell, beta-thalassemia, pernicious, and drug-induced variants.24-26 Several mechanisms may contribute to the retinal findings: hypoxia can compromise retinal blood vessel wall integrity, iron deficiency can reduce red blood cell deformability, and degraded blood elements can increase hypercoagulability, viscosity, and venous pressure, contributing to thrombosis formation.23,27,28

Anemic retinopathy can occur in any layer of the retina. Hemorrhages may appear sheet- or boat-like in the subhyaloid space, flame-shaped in superficial retina, or as dot and blot hemorrhages in deeper retinal layers. White-centered retinal hemorrhages, also known as Roth spots, may occur in either the deep or superficial retinal layers. Nerve fiber layer infarcts (cotton wool spots), hard exudates, attenuated arteries, dilated and tortuous veins, and optic nerve edema or atrophy may also be encountered.22,25,27,30 Hemorrhage, exudate, or macular edema can lead to visual impairment.26,29 Other ocular complications associated with vision loss include optic disc edema, papilledema, and ischemic optic neuropathy.27,28

Other retinal vascular disorders must be ruled out in cases of suspected anemic retinopathy. Conditions that resemble anemic retinopathy include hypertensive retinopathy, non-proliferative diabetic retinopathy, radiation retinopathy, Terson syndrome and Valsalva retinopathy. Roth spots are associated with multiple system illnesses besides anemia, most notably bacterial endocarditis and leukemia.31 The patient described in this report did not have any of these conditions.

The management of systemic anemia depends on its severity and underlying cause. Hemolytic anemia due to Babesiosis infection typically resolves with appropriate antimicrobial treatment.14 Recommended treatment for symptomatic infection consists of a ten-day course of oral or intravenous azithromycin and oral atovaquone.5 Clindamycin and quinine may be used as an alternative.15 Individuals with severe conditions and those suffering a rapid decline in hemoglobin are considered to have medical emergencies requiring immediate stabilization. Patients with Hgb levels <8 mg/dl often require blood transfusion in addition to a longer course of antimicrobial therapy.5,15 Transfusion can rapidly decrease parasitemia by replacing parasitized with nonparasitized erythrocytes. It also removes cytokines and toxic by-products of hemolysis.6

Glucocorticoids are the initial treatment for AIHA, with additional immunomodulatory therapy undertaken if an inadequate response is noted.18 Treatment is generally continued until hemoglobin stabilizes (>10 mg/dL) and other hematologic markers normalize, at which point a slow taper is initiated. The general principle of reducing glucocorticoid treatment in AIHA is to use a gradual taper over two to three months.17,18

Retinal examination has been recommended in cases of anemia when Hgb drops below 10 g/dl.24,25 Repeated fundus examinations should be carried out when anemic retinopathy is persistent.25 Treatment centers on the identification and management of the root systemic cause for anemia. Once the underlying etiology is addressed, ocular findings are almost always reversible. Sight-threatening cases are infrequent, but vision loss is possible. Ocular treatment may involve intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor or laser photocoagulation to control retinal complications.

CONCLUSION

The prevalence of the tickborne illness Babesiosis is increasing. Babesiosis can cause hemolytic anemia through both infectious and autoimmune processes. Anemic retinopathy can occur due to Babesiosis and persist beyond the resolution of the systemic disease. Tick exposure should be considered for patients presenting with retinal ischemia, and appropriate laboratory testing should be ordered when indicated.

REFERENCES

- Marx G, Spillane M, Beck A, Stein Z, Powell AK, Hinckley A. Emergency department visits for Tick Bites – United States, January 2017–December 2019. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. April 29, 2021. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/70/wr/mm7017a2.htm#:~:text=Tickborne%20diseases%20are%20spread%20by%20the%20bites%20of,are%20reported%20in%20the%20United%20States%20each%20year.

- Tick-borne diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. September 22, 2011. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/topics/tick-borne/default.html.

- Olson E. What is Babesiosis? A rare tick-borne disease is on the rise in the Northeast. NPR. March 17, 2023. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://www.npr.org/2023/03/17/1164291434/babesiosis-tick-disease-northeast.

- Swanson M, Pickrel h, Williamson J, Montgomery S. Trends in reported babesiosis cases — United States, 2011–2019. MMWR Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2023;72(11):273-277. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7211a1

- Babesiosis. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. October 30, 2017. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/dpdx/babesiosis/index.html.

- Krause P, Daily E. Babesiosis: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis. UpToDate. September 28, 2023. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/babesiosis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis.

- Raja H, Starr MR, Bakri SJ. Ocular manifestations of tick-borne diseases. Survey of Ophthalmology. 2016;61(6):726-744. doi:10.1016/j.survophthal.2016.03.011

- Ortiz JM, Eagle JC. Ocular Findings in Human Babesiosis (Nantucket Fever). Am J Ophth. 1982;93(3):307-311

- Zweifach PH, Shovlin J. Retinal nerve fiber layer infarct in a patient with Babesiosis. Am J Ophth;1991(5):597-598

- Homer MJ, Aguilar-Delfin I, Telford SR, Krause PJ, Persing DH. Babesiosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2000;13(3):451-469. doi:10.1128/cmr.13.3.451

- Mora P, Carta A. Ocular manifestations of Lyme borreliosis in Europe. Int J Med Sci. 2009;6(3):124-125. doi:10.7150/ijms.6.124

- Babesiosis. Center for Disease Control. July 9, 2024. Accessed January 20, 2025. https://www.cdc.gov/babesiosis/signs-symptoms/index.html

- Narurkar R, Mamorska-Dyga A, Agarwal A, Nelson JC, Liu D. Babesiosis-associated immune thrombocytopenia. Stem Cell Investigation. 2017;4:1-1. doi:10.21037/sci.2017.01.02

- Sanchez E, Vannier E, Wormser GP, Hu LT. Diagnosis, Treatment, and Prevention of Lyme Disease, Human Granulocytic Anaplasmosis, and Babesiosis: A Review. JAMA. 2016;315(16):1767-1777. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2884

- Rajapakse P, Bakirhan K. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia associated with human Babesiosis. J Hematol. 2021;10(2):41-45. doi:10.14740/jh820

- Anemia. Mayo Clinic. May 11, 2023. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/anemia/symptoms-causes/syc-20351360

- Barcellini W, Brodsky RA. Diagnosis of hemolytic anemia in Adults. UpToDate. July 8, 2022 Accessed June 2, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/babesiosis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis

- Brugnara C, Brodsky RA. Warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia in adults. UpToDate.Feb 21, 2024. Accessed August 1, 2024. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/babesiosis-clinical-manifestations-and-diagnosis

- Dionne E, Adelman RA, Cekic O. et al. Retinal integrity in human babesiosis a pilot study. BMC Ophthalmol 24, 310 (2024)

- Shah G, Modi R. Anemic retinopathy: Case reports and disease features. Retina Today. 2016. Accessed June 2, 2024. https://retinatoday.com/articles/2016-may-june/anemic-retinopathy-case-reports-and-disease-features

- Carraro MC, Rosetti L, Gerli GC. Prevalence of retinopathy in patients with anemia or thrombocytopenia. Eur j Haematol 2001;67(4):238-244

- Venkatesh R, Geddy NG, Jaydev C, Chhablani J. Determinants for anemic retinopathy. Beyoglu Eye J 2023;8(2):97-103

- Khuluki RH, Dewi NA, Nugroho S, Wulundari LR. Remarkable result towards retinopathy associated autoimmune hemolytic anemia. IJRetina 2022;5:62-71

- Chew FL, Tajunisah I. Retinal phlebitis associated with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Ocu Immun Inflam 2009;17(6):394-395

- Punjabi S. Devasthali G, Gulati A. Retinal abnormalities in children suffering from low hemoglobin levels. Int J Res Med Sci 2021;9(2):4021-4025

- Vaggu SK, Bhogadi P. Bilateral macular hemorrhage due to megaloblastic anemia: A rare case report. Indian J Ophthalmol 2016:64:157-159

- Biousse V, Rucker JC, Vignal C, et al. Anemia and papilledema. Am J Ophthal 2003;135:437-446

- Saleh T, Green W. Bilateral reversible optic disc edema with iron-deficiency anemia. Eye 2000;14:672-673

- Ayse O, Abdullah O, Hakki D, et al. Bilateral macular hemorrhage associated with autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Retina 2005;25:1089-1090.

- Aisen ML, Bacon BR, Goodman AM, Chester EM. Retinal abnormalities associated with anemia. Arch Ophthalmol 1983;101:1049-1052

- Ruddy SM, Bergstrom R, Tivakaran VS. Roth Spots. [Updated 2023 Jul 17]. In: StatPearls (Internet). July 17, 2023. Accessed June 3, 2025.: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482446/