The Link Between Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus

ABSTRACT

Background

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a condition currently defined as increased intracranial pressure (ICP) in the absence of any secondary causes. While this definition and diagnostic guideline still stands, emerging reports in clinical literature indicate that there are some systemic conditions that are associated with the development of IIH even though the exact pathogenesis has yet to be established.

Case Report

This case report outlines the presentation, diagnosis, and management of IIH in a patient with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). The patient’s pertinent medications also included an etonogestrel implant and hydroxychloroquine. She presented with bilateral disc edema and a history of headaches. Treatment with acetazolamide and topiramate was initiated after MRI and lumbar puncture ruled out underlying pathology and confirmed raised ICP. The patient’s condition was co-managed with neurology and rheumatology, whose recommendations included the discontinuation of prescribed hormonal birth control and hydroxychloroquine, as well as establishing tight control of her SLE to reduce risk factors that could exacerbate IIH.

Conclusion

Bilateral optic disc edema can be an ocular complication of multiple serious conditions. This case discusses the potential link between IIH and SLE as proposed in emerging literature and emphasizes the importance of an interdisciplinary approach in managing these conditions.

Keywords: idiopathic intracranial hypertension, pseudotumor cerebri, papilledema, optic disc edema, systemic lupus erythematosus

INTRODUCTION

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension (IIH) is a condition involving a symptomatic increase in intracranial pressure (ICP) without an identifiable etiology. It commonly affects overweight women between the ages of 25 and 36 years, but can also be found in men and children. The presentation of IIH can be variable between patients, but typically involves a combination of signs and symptoms such as headaches, transient visual obscurations, pulsatile tinnitus, and papilledema. While the pathogenesis of ICP dysregulation is not yet clearly understood, there are several potential theories currently proposed by researchers. Intracranial mechanisms that could raise ICP include CSF hypersecretion at the choroid plexus, CSF outflow obstruction across arachnoid granulations, and increased venous sinus pressure.1 There are also theories exploring the relationship between IIH and obesity as one study found how increased abdominal mass can raise intrathoracic pressure which can also lead to increase in venous pressure.2

This condition can also occur secondary to factors such as medications, hormonal factors, anemia, respiratory dysfunction, chromosomal disorders, renal failure, and autoimmune disorders. Medications that have been associated with IIH include antibiotics such as tetracyclines, excess vitamin A and retinoids, corticosteroids, lithium, and cyclosporin. Disorders or systemic conditions that have been associated with IIH include anemia, hormonal dysfunction, obstructive sleep apnea, Down’s syndrome, systemic lupus erythematosus, and Sjogren’s syndrome.1

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disorder that can affect many organs of the body.3 The pathophysiology of SLE involves the production of autoreactive dendritic cells as part of the innate immune system, stimulation of autoreactive CD4 T cells and B cells as part of the adaptive immune system, and the production of autoantibodies and inflammatory cytokines. Ophthalmic manifestations of SLE can include vasculitis, vascular thrombosis, complications of the neuromuscular junction, optic neuritis, ischemic optic neuropathy, and intracranial hypertension.4 Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations of SLE can include vasculitis, vascular thrombosis, inflammation or ischemia of the optic nerve, and idiopathic intracranial hypertension.3

This report presents a case of an overweight female patient with known history of SLE who developed IIH and required an interdisciplinary approach for proper management of her condition including primary care, neurology and rheumatology. As obesity becomes more prevalent in the younger population, it is imperative to accurately diagnose and manage this condition as early as possible.

CASE REPORT

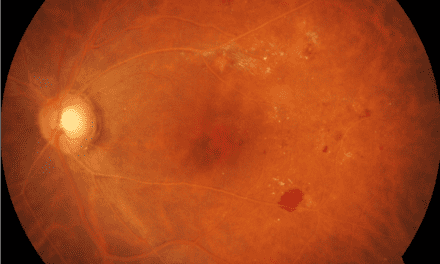

A 32 year-old Hispanic female presented to the eye clinic for a baseline ocular evaluation as she was starting treatment with hydroxychloroquine for her lupus. The patient stated that she had also been getting headaches for the past few years and they had worsened recently. She had no ocular complaints and her best corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in each eye. Confrontation fields were full in both eyes and her pupils were round, reactive to light and without any afferent pupillary defect. IOP checked with Goldmann tonometry was normotensive at 12 mmHg OU. Funduscopic evaluation revealed bilateral edematous optic nerves and no evidence of bulls-eye maculopathy. Visual field testing was unremarkable in both eyes without any enlarged blind spots. Optical coherence tomography (OCT) of the optic nerve showed thickened retinal nerve fiber layer (RNFL) in both eyes greatest in the superior, nasal and inferior quadrants. OCT of the macula showed normal foveal contours without any RPE changes in both eyes. Blood pressure in the office was 130/69 right arm sitting. In addition, the patient reported that she had gained about 50 lbs over the past five years. The patient was sent for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evaluation and lumbar puncture after this visit. The MRI showed a partially empty sella turcica with no apparent orbital or intracranial mass or abnormality. The patient was then lost to follow up and thus did not have a lumbar puncture done immediately after the MRI.

Patient returned for an exam 3 months after the initial presentation. She noted that her headaches had been stable but she was now symptomatic for numbness in her hands as well as worsening difficulty with memory. Her vision was 20/20 OD/OS and pupil testing and confrontation visual fields were unremarkable. The ocular exam revealed worsened bilateral disc edema confirmed by OCT comparison. The patient was able to have a lumbar puncture done one week after this follow up, which revealed an elevated opening pressure of 50 cmH20 (normative range: 5-20 cmH20).5 The constituents of the CSF were normal.

A diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension was made based on the revised Dandy criteria including presence of papilledema, headaches, unremarkable MRI, elevated ICP, and no apparent causative etiology. The patient was started on acetazolamide and topiramate by her primary care physician and educated on the importance of weight loss. She was also referred for management with neurology.

The neurology consultation included a thorough review of the patient’s history and medical testing, as well as a neurologic exam of mental status, cranial nerve function, motor function, sensory function, gait, coordination, and reflexes. The findings from the neurological exam were all unremarkable aside from observed bilateral disc edema. The patient’s neurologist confirmed that the patient’s presentation and clinical findings were most consistent with IIH based on the presence of ONH edema with unremarkable MRI and evidence of increased ICP on lumbar puncture. The neurologist recommended continuing treatment with acetazolamide and topiramate, continuing to encourage weight loss, and re-evaluating her treatment with hormonal birth control and hydroxychloroquine. After consultation with rheumatology, it was decided that the patient should stop treatment with hydroxychloroquine, and raised concerns that her IIH was associated with SLE, so better control of SLE was planned to be established with alternative therapies.

The patient was re-evaluated with a comprehensive eye exam approximately six months after the neurology consultation. She was still being treated with topiramate and her disc edema was nearly resolved. She is being monitored by a rheumatologist every three months to maintain close control of her SLE and had been switched from hydroxychloroquine to azathioprine after the initial diagnosis of IIH. Patient is still being followed by a neurologist and the plan is to continue annual monitoring with optometry for dilated eye exam, OCT imaging, and disc photos.

DISCUSSION

There are several etiologies that need to be investigated in cases of bilateral optic disc edema, as outlined in Figure 1.6 Pseudopapilledema due to optic nerve head drusen must also be ruled out in cases of suspected disc edema, although disc drusen and disc edema can coincide.6

Upon initial presentation, evaluation of patients with suspected disc edema should include perimetry, dilated fundus evaluation, and optical coherence tomography (OCT) imaging.7 Visual acuity, pupil testing and color vision testing are used to assess optic nerve function, although they are typically normal until advanced disease. Perimetry is also used to evaluate optic nerve function, specifically for an enlarged blind spot, which is the most common defect seen with disc edema. OCT imaging can be used to evaluate for disc edema, monitor for progression and differentiate it from optic nerve head drusen.7 Once bilateral optic disc edema has been appropriately diagnosed, the etiology must then be investigated emergently as many causes of bilateral disc edema can be vision or even life-threatening.

As IIH is a diagnosis of exclusion, an extensive workup to rule out potential other etiologies of disc edema is required. The first test that can be performed in the office is taking a blood pressure reading as it is important to first rule out a hypertensive emergency. After ruling out stage 4 hypertension, the next step would be to order an MRI.7 This is done to rule out any intracranial abnormalities such as a tumor or intracranial hemorrhage. Magnetic Resonance Venography (MRV) also recommended to rule out venous sinus thrombosis. If this imaging shows no relevant pathologies, the next step of the workup is to do a lumbar puncture. This is done to evaluate the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) opening pressure as well as to screen the composition of CSF for any infectious or inflammatory markers.7 The differential diagnoses in Figure 1 can be quickly narrowed down in this case by obtaining a very thorough systemic history, taking the patient’s blood pressure reading, ordering blood work, and ordering an MRI.

Idiopathic intracranial hypertension is currently diagnosed based on the modified Dandy criteria: 1) awake and alert patient; 2) symptoms and signs of increased intracranial pressure; 3) absence of focal signs on neurologic examination (excluding CN VI palsy); 4) normal diagnostic studies except for increased intracranial pressure; 5) no other etiology for increased intracranial pressure identified.7 With the use of this criteria, this patient’s diagnosis of IIH was confirmed.

The proposed pathophysiology of IIH involves an understanding of the mechanism of CSF production and drainage. The pathway of cerebrospinal fluid in the brain is still debated, but the current theory is widely accepted among researchers. The majority of CSF is produced by the choroid plexus in the ventricles of the brain. CSF then moves from the lateral ventricles to the fourth ventricle, the subarachnoid space, and then into systemic circulation. The mechanism of CSF drainage into circulation is still widely debated. Current theories involve the role of the arachnoid villi, lymphatic drainage, continuous fluid exchange, and glymphatics.8

Just as the mechanism of CSF flow and drainage being a cause of increased ICP is still debated, there is also debate around the pathophysiology of IIH. One proposed mechanism involves hypersecretion of the CSF, although this theory is less likely as it was unsubstantiated by several studies.1 Another potential mechanism involves an obstruction of CSF outflow, which is complicated by the poor understanding of CSF drainage.1,12 The role of venous sinus pressure as a factor in IIH has also been studied but has not yet been supported. Current studies have focused more on the role of obesity and related inflammatory markers as well as the role of hormones.1

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is an autoimmune disease that primarily affects adult women, although the exact incidence and prevalence is still being studied. Signs and symptoms of lupus include fatigue, fever, and weight changes. Lupus also impacts several organ systems throughout the body with about 30% of patients having ocular manifestations. Ocular sequelae of lupus can range from benign concerns such as keratoconjunctivitis sicca to vision threatening complications such as optic neuritis.4 Neuro-ophthalmic manifestations can also occur, both from SLE directly and from the vascular complications that it causes.3 There are several categories of medications that can be used to treat lupus, including corticosteroids, antimalarials, immunosuppressive agents, and biologic agents.4 Hydroxychloroquine is an antimalarial medication commonly used to treat lupus. At the time of this report, there is no available literature discussing a potential relationship between the use of hydroxychloroquine and the incidence of intracranial hypertension.

IIH as a disorder secondary to SLE has been discussed in several emerging reports, but is not yet widely accepted. There are, however, several published case reports linking the two conditions, and even discussing IIH as an initial presentation for undiagnosed SLE.9 While the exact relationship between these two conditions has yet to be proven, there has been a suggested hypothesis that the autoimmune nature of SLE impacts anti-phospholipid antibodies that are associated with venous thrombosis or stenosis causing decreased CSF absorption.3

Several treatment and management options have been explored for IIH, ranging from conservative measures to surgical intervention. Research has shown that weight loss between 6-10% of original body weight is often enough to resolve IIH.10 Treatment with acetazolamide is widely used in the management of IIH as evaluated in the Idiopathic Intracranial Hypertension Treatment Trial (IIHTT).1 Additionally, topiramate is becoming more popular in treating IIH, and has the added benefit of treating migraine headaches which are common with this condition.11 There are also preliminary studies that have shown topiramate to be more effective in lowering ICP than acetazolamide in animal models.12 More invasive surgical treatments, such as CSF shunting, venous sinus stenting, and optic nerve sheath fenestration, are also used depending on the severity of the condition.12 At this time, further research is needed to compare the effectiveness of different medical therapies for IIH to provide clinicians with better evidence-based treatment options.

A paper by Thurtell outlines a treatment and management approach to IIH based on the severity of the condition grade based on severity of visual field loss.7 This report suggested that patients with minimal vision loss, or a mean deviation on visual field better than -3 dB can be managed with weight loss alone. Patients with IIH and mild visual field loss, or a mean deviation on visual field between -3 dB and -7 dB should be managed with weight loss and medical therapy. IIH resulting in moderate visual field loss, or -7 dB to -15 dB mean deviation, should be treated with weight loss and aggressive medical therapy and surgical options can be considered. IIH resulting in severe vision loss or a mean deviation greater than -15 dB on visual field testing require weight loss, aggressive medical therapy, and surgical intervention.7 This system of management is more of a clinical guideline, and may need to be adjusted as the condition is monitored and the effectiveness of therapy options for that individual patient are established.

CONCLUSION

Bilateral optic disc edema can be an ocular complication of several serious conditions. An urgent and thorough workup of disc edema is always warranted. If no secondary cause of disc edema is found along with an elevated intracranial pressure, a diagnosis of idiopathic intracranial hypertension can be made. At this time the exact mechanism of CSF outflow is still being debated, which in turn makes it difficult to understand the mechanism of IIH as a secondary condition to other systemic factors. Emerging literature suggests a potential relationship between SLE and IIH, although the causative mechanism has yet to be understood. Further research into the pathophysiology of both IIH and SLE is necessary to create a foundation for the understanding of the relationship between these two conditions. The patient in the case presented had both IIH and SLE, and it is likely that co-managing each condition together was important in the resolution of the patient’s optic disc edema.

REFERENCES

- Markey KA, Mollan SP, Jensen RH, Sinclair AJ. Understanding idiopathic intracranial hypertension: Mechanisms, management, and Future Directions. The Lancet Neurology. 2016 Jan;15(1):78–91.

- Sugerman HJ, DeMaria EJ, Felton WL, Nakatsuka M, Sismanis A: Increased intra-abdominal pressure and cardiac filling pressures in obesity-associated pseudotumor cerebri. Neurology 1997; 49: pp. 507-511.

- Man BL, Mok CC, Fu YP. Neuro-ophthalmologic manifestations of systemic lupus erythematosus: A systematic review. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2014;17:494–501.

- Fortuna G, Brennan MT. Systemic lupus erythematosus. Dental Clinics of North America. 2013;57(4):631–55.

- Hrishi AP, Sethuraman M. Cerebrospinal Fluid (CSF) Analysis and Interpretation in Neurocritical Care for Acute Neurological Conditions. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2019 Jun;23(Suppl 2):S115-S119. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10071-23187. PMID: 31485118; PMCID: PMC6707491.

- Smith S, Puckett E. Bilateral optic disc edema [Internet]. EyeWiki. 2022 [cited 2022Apr27]. Available from: https://eyewiki.org/Bilateral_Optic_Disc_Edema

- Thurtell MJ. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension. CONTINUUM (MINNEAP MINN). 2019;25(5):1289–309.

- Bothwell SW, Janigro D, Patabendige A. Cerebrospinal fluid dynamics and intracranial pressure elevation in neurological diseases. Fluids Barriers CNS. 2019 Apr 10;16(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12987-019-0129-6. PMID: 30967147; PMCID: PMC6456952.

- Rajasekharan C, Renjith SW, Marzook A, Parvathy R. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension as the initial presentation of systemic lupus erythematosus. BMJ Case Reports. 2013;2013(jan31 1).

- Subramaniam S, Fletcher WA. Obesity and weight loss in idiopathic intracranial hypertension: A narrative review. Journal of Neuro-Ophthalmology. 2017;37(2):197–205.

- Raoof N, Hoffmann J. Diagnosis and treatment of idiopathic intracranial hypertension. Cephalalgia. 2021;41(4):472–8.

- Scotton WJ, Botfield HF, Westgate CSJ, Mitchell JL, Yiangou A, Uldall MS, et al. Topiramate is more effective than acetazolamide at lowering intracranial pressure. Cephalalgia. 2018;39(2):209–18.