Behcet’s Disease Flares Up BADS: A Bilateral Anterior Diffuse Scleritis Case Report

ABSTRACT

BACKGROUND

Anterior scleritis is an inflammation of the sclera defined by deep ocular erythema, intense and boring eye pain that can radiate to the forehead or brow, photophobia, and decreased vision. Scleritis is a rare ocular condition in any case, but a majority of patients diagnosed with any of the categories of scleritis tend to have an underlying systemic cause. Though infrequent, scleritis is one of the ocular manifestations of Behcet’s disease. Management of an ocular inflammatory condition in conjunction with a comorbid inflammatory systemic disease can be extremely challenging due to the sight-threatening nature of the relationship.

CASE REPORT

In this case, a patient with a known diagnosis of Bechet’s disease presented to the clinic with an acute first-time episode of bilateral anterior diffuse scleritis. Oral steroids served well to manage the ocular inflammatory flare-up of bilateral anterior diffuse scleritis in this patient; however, further systemic management with the assistance of a rheumatologist was sought after for long-term maintenance of the patient’s condition.

CONCLUSION

This case report serves as an example of scleritis management in a patient with a co-morbid vasculitic condition as well as an example of oral steroid management of anterior scleritis rather than the typical oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) route.

Keywords: anterior diffuse scleritis, Behcet’s disease

INTRODUCTION

Behcet’s disease is a relapsing, multisystem vasculitis that can affect any organ system and preferentially affects mucous membranes like the mouth, skin, and eyes.1-4 Behcet’s disease is extremely rare, but most commonly affects those of Mediterranean, Middle Eastern, and Japanese descent with an association between the HLA-B51 allele and populations with increased frequency of Behcet’s disease.1,3,4 Due to the heterogenous presentation, rarity, and recurrent nature of the condition, Behcet’s disease is very challenging to treat and does not have a standardized treatment regimen.3,4 Furthermore, ocular manifestations are common in patients with Behcet’s disease and can cause sight-threatening changes when not properly managed. The most common ocular presentation is uveitis, while the most severe presentations are posterior segment changes such as obliterative necrotizing retinal vasculitis.1-4 This case, however, serves to illustrate the management approach of one case with a rarely associated ocular manifestation: bilateral anterior diffuse scleritis.

CASE REPORT

Initial Problem-Focused Examination

A 51-year-old male patient presented to the clinic with a primary complaint of red, painful eyes that began three days prior. He described concurrent photophobia – which was worse over the course of the presentation – and a co-morbid headache localized over the brows which radiated from the eyes bilaterally. The patient also stated his vision was blurrier than usual at the time of the appointment. When further questioned, the patient reported his eyes had been matted shut when he woke up that morning and the previous morning. The patient had tried many treatments before seeking care: allergy eye drops, washing his face and eyes, and cool compresses.

The patient had a positive ocular history for a “sore within the eye” of the left eye, which was treated with steroid eye drops, bandage contact lens, and ointment per the patient. Otherwise, the patient reported no other personal ocular history beyond the use of over-the-counter readers. The patient reported negative family ocular history.

His medical history was positive for hyperlipidemia, migraine, bipolar type 1, and Behcet’s disease. Regarding the patient’s Behcet’s disease, he reported receiving this diagnosis in his young twenties. The patient had a history of several outbreaks since diagnosis, including sores of the mouth, throat, and skin, especially early on in the course of the disease, whereas later on, the patient reported more joint pain and eye symptoms. He reported previous use of colchicine or prednisone for outbreaks of inflammation but denied use for several months or longer at the time of the initial appointment in this report. He reported extensive testing to rule out STI-related causes of symptoms.

Upon ocular evaluation, the patient’s uncorrected distance visual acuities were 20/40 right eye (pinhole 20/25) and 20/50 left eye (pinhole 20/40). His pupils were reactive to light; however, the patient was extremely photophobic – so much so that the swinging flashlight test was unable to be performed. The patient displayed full and comitant extraocular muscle movements, but he described pain in all gazes with the worst pain in bilateral superior gazes. Unaided cover test in the distance showed no tropia nor phoria. Confrontation fields were full-to-finger-counting in both the right and left eye.

Anterior segment evaluation showed 4+ diffuse bulbar and palpebral conjunctival injection bilaterally with distinct scleral vessel engorgement (deduced using a cotton swab and attempting to move the non-mobile vessels). Upon instillation of 2.5% phenylephrine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution in both eyes, the tissues showed slight, but incomplete blanching of injection. The anterior chamber of both eyes were deep and quiet without cells nor hypopyon and appeared open using the Van Herrick method. Goldmann tonometry values were 18 mmHg in the right and left eye. Dilated evaluation of the posterior segment was within normal limits except for slight venous engorgement in both eyes. There were no signs of vitritis, retinal vasculitis, venous obstruction, arterial attenuation, nor retinal detachment.

Several differential diagnoses were considered including bilateral acute bacterial conjunctivitis, bilateral subconjunctival hemorrhage, bilateral acute anterior uveitis, bilateral retinal vasculitis, bilateral episcleritis, and bilateral anterior diffuse scleritis. Most prominently, scleritis is defined by an intense and boring eye pain that can radiate to the forehead or brow and which may worsen with eye movements.5,6 Ocular erythema with subjective signs of photophobia and decreased vision are also characteristic of scleritis.5,6 Furthermore, objective signs include inflammation of the sclera, episcleral, and conjunctival vessels wherein the deepest vessels are immobile with a cotton-swab and do not blanch with topical 2.5% phenylephrine ophthalmic solution.5 Although it is well documented in the literature that scleritis is a rare ocular manifestation of Behcet’s disease,3,4,6 the patient’s clinical presentation well-aligned with the aforementioned findings and the diagnosis was made.

The patient was extensively educated on the inflammatory nature of the ocular ailment as well as the high likelihood of its connection to his chronic inflammatory systemic condition. Due to the nature of the condition diagnosed, the patient was prescribed oral prednisone: 60 mg by mouth daily for one week. It was discussed with the patient that treatment with steroids involves a long taper and then the patient was lengthily educated on the likely taper down to 40 mg daily for one week, 20 mg daily for one week, followed by 10 mg daily for one week.

The patient was informed that he should establish additional health services with a rheumatologist. At this point, the patient expressed a mistrust of the healthcare system – he had previously been “poked and prodded,” as he described it, in order to find his diagnosis, and he had undergone multiple treatment methods, which he felt debilitated his life, including the use of chemotherapy and methotrexate.

Follow-up #1 (Day 5)

The patient presented for his first follow-up appointment. He reported the condition of his eyes had improved since beginning the oral steroid regimen: less pain and light sensitivity. Moreover, the patient reported improved vision which was confirmed with uncorrected visual acuities in the distance measured as 20/25 right and left eye.

Regarding anterior segment findings, there were also signs of improvement: the patient had 3+ diffuse conjunctival injection bilaterally with distinct scleral vessel engorgement. With instillation of 2.5% phenylephrine hydrochloride ophthalmic solution in both eyes, the tissues showed moderate, but incomplete blanching of injection. Dilated ocular evaluation with an additional drop of 0.5% tropicamide ophthalmic solution was again within normal limits albeit slight retinal venous engorgement of both eyes.

To ensure the oral steroids were not affecting the patient’s intraocular pressures, tonometry was performed: 22 mmHg right eye and 19 mmHg left eye.

Follow-up #2 and Comprehensive Eye Exam (Day 18)

The patient presented with uncorrected visual acuities in the distance measured as 20/25 right and left eye. Best corrected visual acuities were 20/20 right and left eye with manifest refraction.

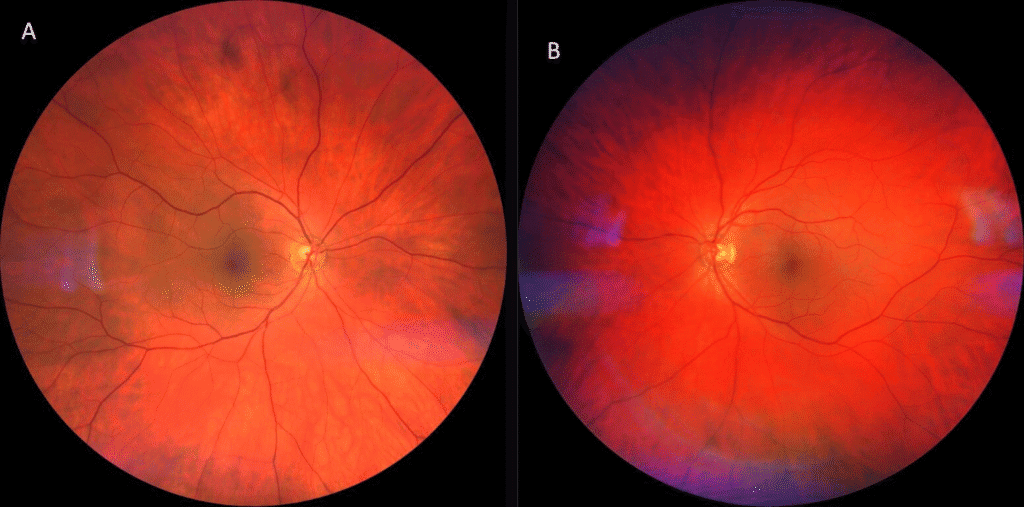

Ocular examination revealed further signs of improvement: the patient had 2+ diffuse conjunctival injection bilaterally with less distinct scleral vessel engorgement. The patient was not dilated at this appointment, and instead, posterior segment health was assessed using undilated fundoscopy as well as widefield fundus photography (Figure 1). Posterior segment evaluation was again within normal limits, albeit with minimal retinal venous engorgement of both eyes.

The patient was educated on the resolving nature of his condition and the need for continued steroid taper as a part of his treatment plan. The patient was told to finish the week taking 20 mg prednisone daily and then to begin a 10 mg daily dosage.

Figure 1. Widefield fundus imaging of the patient’s right (A) and left (B) posterior segment. Photography revealed a posterior segment within normal limits albeit minimal retinal venous engorgement of both eyes. There were no obvious signs of vitritis, retinal vasculitis, venous obstruction, arterial attenuation, or retinal detachment.

Ophthalmology Referral

It was the opinion of the uveitis specialist that the patient’s scleritis was resolved; due to the patient’s history, the uveitis specialist initiated the process for the patient to begin taking adalimumab. The patient was scheduled to return to the clinic for a full workup by a retinal ophthalmologist. It was stated in their report that they would also place a referral for rheumatology management in an attempt to convey the urgency of this patient’s need for systemic care.

Rheumatology Electronic Consult (Day 35 and 39)

The initial community care rheumatology consult placed was denied for this patient due to rheumatology staffing shortages at the time. Thus, an electronic consult (e-consult) with rheumatology was placed conveying the patient’s history with Behcet’s disease as well as the onset, diagnosis, and management of the current scleritis episode. The e-consult stated that, assuming resolution of the ocular symptoms, it was recommended that the patient continue at the 5 mg dosage of oral prednisone for a total of four weeks, then discontinue. Furthermore, it was suggested that if he was having frequent outbreaks, long-term treatment consideration should include colchicine 0.6 mg daily.

DISCUSSION

It is important to understand the pathophysiological differences between episcleritis and scleritis, and therefore the anatomical differences between the episclera and the sclera. The sclera composes the posterior 5/6 of the globe and is considered avascular because it has no capillary beds of its own; though, many blood vessels travel through the sclera.7 Supplied by the ciliary arteries, the vascular episclera overlies the avascular sclera and serves to supply the sclera with nutrients.8,9 Due to the anatomical layering of the loose and mobile conjunctival plexus, the slightly mobile and radially oriented vessels of the superficial episcleral plexus, and the immobile criss-crossing vessels of the deep episcleral plexus, clinicians are able to deduce the extent of inflammation to discern between the differential diagnoses of episcleritis versus scleritis.8 Additionally, coloration of the inflammation can aid in differentiating the depth of vasculature involved: bright red conjunctival plexus inflammation, salmon pink superficial plexus inflammation, or bluish-red deep episcleral plexus inflammation.8 Clinically, the deepest vessels do not blanch with topical 2.5% phenylephrine ophthalmic solution5 which can be a major differentiator between episcleritis and scleritis.

Scleritis is a diverse and complex inflammation of tissue which can be sub-categorized in many ways. Most easily, scleritis can be either anterior or posterior; anterior scleritis can be further divided into diffuse, nodular, or necrotizing scleritis.8 Anterior scleritis is defined as a painful inflammation of the scleral tissues anterior to the insertion points of the extraocular muscles. This disease process causes erythema of the eyes and is one of the few ocular conditions that causes severe pain.8 The pain can be described as dull, boring, and/or severe as well as either localized to the eye itself or radiating along the trigeminal nerve and causing referred pain to the forehead and brow.5,8 Diffuse scleritis is most common in women and typically presents in the fifth decade; however, in men, a peak prevalence occurs in the fourth decade.6,8,9 Immune-mediated (non-infectious) scleritis is the most common type of scleritis.6 And, while scleritis is an uncommon ocular manifestation in any case, a majority of patients with any of the classifications of scleritis have an underlying systemic cause.5,6 The most common systemic association with scleritis is rheumatoid arthritis.6,8,10

The management method for anterior diffuse scleritis has developed over the years. Nevertheless, one treatment approach has remained constant: topical therapeutics are not sufficient treatment for scleritis and may only serve to reduce irritation and provide comfort.6,8 Oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are first line therapy for the treatment of non-necrotizing anterior scleritis.6,8-10 One of the most commonly prescribed NSAIDs is indomethacin 100 mg daily followed by a reduced dosage of 75 mg daily until the scleritis resolves, which typically takes about one month of therapy.8,10 If the scleritis is severe and/or oral NSAIDs fail, patients are initiated on oral steroids with the typical dosage being 1 mg/kg/day.6,8-10 With resolution, the steroid regimen must then be slowly tapered over the course of a month or longer.5,6,8,10 The final line of therapy is immunosuppressive agents such as cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, cyclosporine, or others.5,6,9,10 Cyclophosphamide is among the most commonly prescribed immunosuppressive drugs for scleritis due to its frequent use in vasculitic conditions with the initial dosage recommended at 2 mg/kg/day in addition to oral steroid therapy. Patients who are initiated on immunosuppressive therapy should be closely co-managed with an internist or rheumatologist due to the side effects of therapy and the likely systemic comorbidity driving the scleritis in the first place.5,9

Connective tissue and vasculitic disorders are regularly associated with scleritis including rheumatoid arthritis, granulomatosis with polyangiitis, relapsing polychondritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and others.5,9,10 Though extremely uncommon, scleritis is one of the ocular manifestations of Behcet’s disease.1-5 The etiology of Behcet’s disease (BD) itself is still not well understood, but what is known is that it is a relapsing, multisystem vasculitis which can affect any organ system and preferentially affects mucous membranes like the mouth, the skin, and the eyes.2-4 According to the Criteria of the International Study Group 1990, a diagnosis of BD can be made based on recurrent oral aphthous ulcers plus two of the following: recurrent genital ulcerations, eye lesions (such as anterior uveitis, posterior uveitis, vitritis, or retinal vasculitis), skin lesions, or positive pathergy testing.3,4 Behcet’s disease is rare, but it most commonly affects those of Mediterranean and/or Japanese descent with onset most frequently between twenty and forty years of age.1-4 Additionally, there is an association between the HLA-B51 allele and populations with increased frequency of Behcet’s disease.1,3,4

Ocular manifestations of BD are common, occurring in up to 70% of patients.1-4,11 Its most common ocular sign is uveitis in some variety whether it is unilateral anterior uveitis or bilateral panuveitis; however, the most sight-threatening ocular manifestation is an obliterative necrotizing retinal vasculitis.1-4,11 Another posterior segment finding which is not indicative of retinal vasculitis per se, but is related to BD (due to the nature of it being the only systemic vasculitis affecting small and medium-sized arteries as well as veins) is venous engorgement4 – which was present in the patient in this case. Other inflammatory presentations less commonly associated with Behcet’s include anterior segment findings such as conjunctivitis, episcleritis, scleritis, corneal changes like keratitis, and, even more rarely, extraocular muscle paralysis.3,4

Treating ocular BD is challenging due to its heterogeneous nature, presentation of the condition, and rarity.3,4,12,13 Even as recent as the year 2023, at the 19th International Conference on BD, no standardized treatment regimen exists for Behcet’s disease.3,4,12,13 Currently, immunosuppressive therapy of some variety is typically required for the treatment of BD. When the eye is involved, colchicine, NSAIDs, or low-dose oral steroids are typically insufficient for long-term monotherapy.3,4,12 Colchicine is a first-line therapy when the disease has mucocutaneous or articular manifestations, but it is not considered helpful for ocular manifestations.12 It is important to note that many studies support the use of oral steroids as an initial treatment method for acute ocular inflammation (especially in the absence of posterior involvement) which supports the decision made in this case to initiate the patient on oral steroids as first-line therapy rather than oral NSAIDs as suggested by the typical scleritis management flow.3,4,12

Past literature regarding the treatment of ocular BD relates to diagnoses of either uveitis or retinal vasculitis. However, recent literature on the management of ocular BD suggests that patients should seek treatment with immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine A, azathioprine, interferon alpha (IFN-α), or tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) antagonists for long-term management.3,4,12 Treatment with these classes of drugs, which are immunosuppressant and immunomodulatory in nature, is most critical in ocular BD when there is vitreous or posterior segment involvement.4,12

CONCLUSION

This case demonstrates how the management of an ocular inflammatory condition in conjunction with a comorbid inflammatory systemic disease can be challenging due to the sight-threatening nature of the relationship. In this case, oral steroid therapy quelled the inflammation and resolved the ocular flare-up. This case served to demonstrate the effectiveness of oral steroid therapy as an initial therapeutic option for the management of a bilateral anterior scleritis outbreak secondary to Behcet’s disease. Though oral steroid therapy may not have been the first line therapy suggested for scleritis alone, it was warranted, given the scleritis episode was likely secondary to Behcet’s disease. Additionally, co-management with a rheumatologist is important when treating patients with ocular Behcet’s disease due to the chronic nature of the condition and the possibility of vision loss. Further systemic management with the assistance of a rheumatologist was sought for long-term care of this patient. The fact that the patient did not have established rheumatological care made the hand-off for this case difficult, since Behcet’s disease is a chronic condition and requires lifelong therapy and management. Luckily, this patient initiated the referral process as part of his management strategy. The patient’s return to optometric care helped orchestrate a trust in the healthcare system again for this patient which led to better overall long term management for his systemic disease.

References

- Classification Criteria for Behçet Disease Uveitis. (2021). American Journal of Ophthalmology, 228, 80–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajo.2021.03.058

- Tugal-Tutkun, I. (2023). Uveitis in Behçet disease—An update. Current Opinion in Rheumatology, 35(1), 17–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/BOR.0000000000000911

- Deuter, C., Kotter, I., Wallace, G., Murray, P., Stubiger, N., & Zierhut, M. (2008). Behçet’s disease: Ocular effects and treatment. Progress in Retinal and Eye Research, 27(1), 111–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.preteyeres.2007.09.002

- Zierhut, M., Stubiger, N., Deuter, C., & Kotter, I. (2005). Behcet’s Disease. In U. Pleyer & B. Mondino (Eds.), Uveitis and Immunological Disorders (pp. 173–200). Springer.

- Gervasio, K. A., Peck, T. J., Fathy, C. A., Sivalingam, M. D., Friedberg, M. A., & Rapuano, C. J. (Eds.). (2022). The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease (Eighth). Wolters Kluwer.

- Salmon, J. (2020). Chapter 9—Episclera and Sclera. In Kanski’s Clinical Ophthalmology (Ninth, pp. 291–305). Elsevier Limited.

- Remington, L. A. (2012). Chapter 2—Cornea and Sclera. In L. A. Remington (Ed.), Clinical Anatomy and Physiology of the Visual System (Third Edition) (pp. 10–39). Butterworth-Heinemann. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-4377-1926-0.10002-5

- Watson, P. G., & Hayreh, S. S. (1976). Scleritis and episcleritis. The British Journal of Ophthalmology, 60(3), 163–191.

- Albini, T. A., Rao, N. A., & Smith, R. E. (2005). The Diagnosis and Management of Anterior Scleritis: International Ophthalmology Clinics, 45(2), 191–204. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.iio.0000155900.64809.b2

- Jabs, D. A., Mudun, A., Dunn, J. P., & Marsh, M. J. (2000). Episcleritis and scleritis: Clinical features and treatment results. American Journal of Ophthalmology, 130(4), 469–476. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-9394(00)00710-8

- Ksiaa, I., Abroug, N., Kechida, M., Zina, S., Jelliti, B., Khochtali, S., Attia, S., & Khairallah, M. (2019). Eye and Behçet’s disease. Journal Français d’Ophtalmologie, 42(4), e133–e146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfo.2019.02.002

- Alibaz-Oner, F., & Direskeneli, H. (2021). Advances in the Treatment of Behcet’s Disease. Current Rheumatology Reports, 23(6), 47. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-021-01011-z

- Fragoulis, G. E., Bertsias, G., Bodaghi, B., Gul, A., Van Laar, J., Mumcu, G., Saadoun, D., Tugal-Tutkun, I., Hatemi, G., & Sfikakis, P. P. (2023). Treat to target in Behcet’s disease: Should we follow the paradigm of other systemic rheumatic diseases? Clinical Immunology, 246, 109186. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clim.2022.109186