A Multidisciplinary Approach in the Management of Hemifacial Spasm

Abstract

Background: Patients with hemifacial spasm are often misdiagnosed. This is a case report of a patient with eyelid myokymia who presents with worsening symptoms. Proper diagnosis of hemifacial spasm warrants an MRI revealing: microvascular compression displacing the right 7th cranial nerve at the root exit zone. The role of optometrists and different management options are discussed.

Case Report: A 62-year-old Hispanic male presents to the eye clinic complaining of constant spontaneous right lower and upper eyelid spasm worsening over the past 2 years. The patient notes that the twitching becomes worse while in a one-on-one conversation or while arguing. He denies excess intake of caffeine/alcohol, high stress lifestyle, history of Bell’s palsy, stroke, or trauma. Patient’s ocular history is unremarkable, and his medical history is significant for hypertension, well-controlled with oral medications.

Conclusion: Although hemifacial spasm is most often due to benign microvascular compression, a timely and accurate diagnosis is necessary to rule out ominous causes and coordinate future care. Clinicians should be familiar with hemifacial spasm and MRI studies should be promptly completed to confirm the diagnosis, identify etiology, and initiate appropriate treatment.

Keywords: eyelid myokymia, hemifacial spasm, microvascular compression, seventh cranial nerve

Introduction

Hemifacial spasm is a neuromuscular movement disorder characterized by progressive, involuntary, irregular clonic or tonic movements of the muscles innervated by the facial nerve. Typically, the movements are unilateral. In most cases, the etiology is due to facial nerve compression by an aberrant or ectatic blood vessel at the root exit zone at the level of the brainstem.1,3,7 However, it can also result from an insult to the facial nerve due to a more sinister cause such as a tumor, trauma, infection, or vascular anomaly. The orbicularis oculi is often the initial site of spasm, usually involving the lower eyelid with subsequent spread to involve other facial muscles.2,3 Patients with hemifacial spasm often initially present to their optometrist complaining of unilateral involuntary eyelid twitching, therefore it is crucial to accurately diagnose and coordinate appropriate imaging to determine the underlying etiology. This case report reviews how to detect, diagnose, and co-manage hemifacial spasm in a multi-disciplinary team approach.

Case Report

A 62-year-old Hispanic male presents to the eye clinic complaining of constant spontaneous right lower and upper eyelid spasm worsening over the past 2 years. The patient notes that the twitching becomes worse while in a one-on-one conversation or while arguing. He denies excess intake of caffeine/alcohol, high stress lifestyle, history of Bell’s palsy, stroke, or trauma. Patient’s ocular history is unremarkable, and his medical history is significant for hypertension, well-controlled with oral medications.

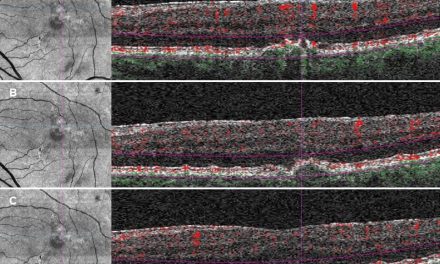

Upon examination, the patient’s Snellen distance visual acuity is 20/20 OD and 20/20 OS. Pupils, EOMs, confrontation visual fields do not show signs of pathology. Color vision is full OD/OS. Hertel exophthalmometry, MRD1 and levator function are symmetric between the two eyes. No pathology was noted in the anterior segment and posterior segment of either eye. On external observation, there is an obvious, constant spasm of the right lower lid, the right upper lid, and the right upper cheek corresponding to the zygomatic muscle. The remainder of cranial nerve testing: CN V, VIII-XII is intact. Right sided upper and lower eyelid spasm with additional involvement of the right zygomatic muscle prompts an MRI of the brain with and without contrast to assess the root and the course of the right facial nerve with attention to the pons/cerebellopontine angle. MRI imaging interpreted by the radiology team detects the right vertebral artery and the right anterior inferior cerebellar artery branch displacing the right seventh cranial nerve at the root exit zone, confirming a diagnosis of primary hemifacial spasm due to microvascular compression.

The patient was referred to the oculoplastic team and received botulinum toxin (BTX) injections along the right lateral upper eyelid, right lateral lower eyelid, right central lower eyelid, and along the malar eminence for a total of 20 units (5 units of 0.1mL at each location). At the two-week follow-up, the patient reported significant improvement in facial spasm, but disliked newly noted facial asymmetry when smiling due to excessive chemodenervation from the botulinum toxin. The oculoplastic team presented two options to the patient: re-administer botulinum toxin injections decreasing the zygomatic injection to only 2.5 units versus a referral to neurosurgery for consideration of microvascular decompression for a more permanent solution. Given the invasive and high-risk nature of microvascular decompression, the patient elected to continue with BTX injections.

Figure 1: Axial-plane high resolution T2-weighted MRI image shows microvascular compression of the facial nerve. The yellow arrow shows R CNVII, the blue arrow shows R CNVIII, the red arrow shows R vertebral artery and the green shows the anterior inferior cerebellar artery branch.

Figure 2: Assessment of CN7 branches showing facial asymmetry 2 weeks s/p botulinum toxin injections on the right side of the patient’s face.

Discussion

The prevalence of hemifacial spasm is rare and data is scarce. However, it’s found to be more common in females and higher in Asian populations.1 The average age of onset is 45-60 years old. 1 Although spontaneous, it can be exacerbated by use of facial expressions and some cases have reported worsening of the spasms with stress, anxiety, and fatigue.3 The correlation is not well understood.

Diagnosis of hemifacial spasm can be challenging. Differential diagnoses include: blepharospasm, synkinesis after facial nerve paralysis, facial myokymia and eyelid myokymia. In contrast to hemifacial spasm, blepharospasm presents bilaterally and proceeds to involuntary spasms with more synchronous, symmetrical and forceful contractures of the orbicularis oculi muscles. 3 Eyelid myokymia is due to unilateral, brief, benign involuntary contractions of the orbicularis oculi, associated with excessive fatigue, sleep deprivation or excessive caffeine consumption. Eyelid myokymia is typically unilateral and affects one muscle at a time. This differs from involuntary the tonic-clonic muscle contractions characteristic of hemifacial spasm. Eyelid myokymia is isolated to the orbicularis oculi muscle but can spread to additional muscles of one or both sides of the face, in which case it is referred to as facial myokymia.8 Facial myokymia is caused by damage to the facial nerve nucleus in the pons from demyelinating diseases such as multiple sclerosis, Guillian-Barre syndrome, pontine gliomas or brainstem lesions. 8

The facial nerve has a short intracranial root from the brainstem to the internal auditory canal. It exits the brainstem at the pontomedullary junction and the cerebellopontine angle. The root exit zone of the facial nerve is defined as the transition point between the central and peripheral cell myelination.5 Therefore, several theories have attempted to explain how compression of the facial nerve at the root exit zone can result in hemifacial spasm. Due to the anatomy in the region, the most common offending vessels are branches of the anterior inferior cerebellar artery and posterior inferior cerebellar artery.3,7 The facial nerve courses with the vestibulocochlear nerve from the brainstem to the internal auditory canal before the facial nerve branches off. Given the proximity of the two structures, any compression to this region could also result in hearing impairment, vertigo or tinnitus.3

The pathogenesis of hemifacial spasm is not well understood, but there are two hypotheses that attempt to explain it: the central theory and the peripheral theory. The central theory proposes that irritation of the peripheral afferent facial nerve fibers leads aberrant signaling to the central facial nucleus causing hyperexcitability and abnormal firing, which in turn results in the involuntary contractions of the facial muscles on the ipsilateral side.4 Conversely, the peripheral theory proposes that the abnormal excessive firing of the facial nerve is due to the demyelination of the facial nerve at the side of insult at the root exit zone, which prevents lateral transmission of impulses to the adjacent fibers, leading to ectopic transmission of impulses.3,4 In summary, the central theory argues that the hyperactivity occurs at the level of the motor nucleus, while the peripheral theory assumes that the abnormal cross-transmission occurs at the level where the facial nerve fibers are being compressed at the root exit zone. As discussed above, the root exit zone is the transition region between the oligodendrocytes and the Schwann cells, making it an area susceptible to insult.

In hemifacial spasm, the orbicularis oculi muscle is often the initial site of spasm, prompting patients to seek evaluation by their eye doctor. Therefore, it is crucial for optometrists to be aware of the differences between hemifacial spasm and its differential diagnoses in order to make an accurate diagnosis and coordinate the appropriate work-up, along with imaging, to determine the underlying etiology. A careful history and a detailed external examination of the patient are essential, but diagnosis is confirmed by MRI of the brain and internal auditory canal evaluating the course and root of the 7th cranial nerve with attention to the pons/cerebellopontine angle. Fortunately, most cases are due to benign anatomical variation of an artery compressing the facial nerve at the root exit zone of the brainstem, as in the case with the aforementioned patient. Such cases are classified as primary hemifacial spasm and are due to microvascular compression of the facial nerve at the root exit zone. On the other hand, secondary hemifacial spasm is due to damage anywhere along the facial nerve root from the internal auditory canal to the stylomastoid foramen from a more serious cause such as a tumor, trauma, infection, demyelinating lesions, or vascular anomaly. An effective method to distinguish between the two types is with MRI. Early and accurate diagnosis allows for facilitation of the appropriate course of management.

Treatment and Management

Botulinum toxin (BTX) injections have revolutionized the treatment of hemifacial spasm allowing for a less invasive treatment option. Local botulinum-toxin injection provides short term relief. Chemo-denervation with BTX safely and effectively blocks the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction to reduce the tone of overactive muscle.7 Some degree of facial asymmetry is very common post-treatment. Direct injection of the zygomaticus major muscle may produce more profound facial asymmetry, particularly when smiling, as was evidenced in the subject of this case report. The orbicularis oculi is innervated by the temporal branch of the facial nerve and with minor innervation from the zygomatic and buccal branches. The zygomaticus complex has a robust role in facial movement, especially in moving the angle of the mouth superiorly, laterally and posteriorly.4,5 Therefore, this muscle is often avoided in BTX treatment as it can result in dramatic facial asymmetry, drooping or lateral lip paralysis. In such patients who are bothered by the asymmetry, a more individualized treatment plan is required in order to either find the right unit dosing of BTX or explore different treatment options.

Common adverse side effects of BTX include ptosis, bruising, tearing, temporary facial nerve paralysis, double vision, nausea and allergic reactions.3,7 The major drawbacks of BTX include limited efficacy, requirement of repeat injections every 3-4 months, and the high associated cost. For this reason, patients may request a more permanent treatment.

Microvascular decompression surgery provides a more permanent and long-term solution in eliminating hemifacial spasm symptoms and improving quality of life. However, given its extremely invasive nature, it is not often the first line of treatment recommended. There are many potential side effects, some of which include facial paresis, hearing loss, vertigo, ataxia, tinnitus, local infection, stroke, and other cranial nerve palsies.3,7 This invasive surgery involves a craniotomy which exposes the brain to relieve the vascular compression at the root-exit zone of the facial nerve. The actual decompression is achieved by placing a Teflon sponge between the offending vessel and the seventh nerve exit zone, thus relieving direct contact.5,7 It is worth noting that although microvascular decompression provides a definite treatment of the spasm, recurrence and relapse has also been reported.

Other treatment options for hemifacial spasm include oral agents like carbamazepine, clonazepam, baclofen, gabapentin, which provide short-term relief. Due to these agents causing several unwanted side effects, including fatigue, exhaustion, and sedation, they are often reserved as a last resort.1,7 Moreover, treatment success in these cases has been poor, sporadic, and inconsistent.1,7

An interesting consideration reported in some studies is the possible association between arterial hypertension and hemifacial spasm. Several case reports have documented arterial hypertension occurring more frequently among patients with hemifacial spasm.2,7,8 Therefore, regular blood pressure monitoring should be advised in patients with hemifacial spasm. Good blood pressure control should be encouraged. Future studies are needed to evaluate the link between the two. In this case, the patient was encouraged to keep a blood pressure log and he was reconnected with his primary care provider for appropriate blood pressure management.

An interprofessional team is essential for optimal care of patients with hemifacial spasm. MRI imaging and radiographic collaboration is important in identifying the cause. Additionally, patients are co-managed with oculoplastics, otolaryngology and neurology for long-term treatment and management. Although hemifacial spasm is typically not life-threatening, it can significantly affect a patient’s quality of life due to associated psychosocial stress. Hemifacial spasm is involuntary, and in many cases the condition leads to anxiety and social embarrassment. Accurate diagnosis, patient education, and timely management are all key elements to improve the quality of life in these patients.

Conclusion

This case highlights the role of optometrists in a multidisciplinary collaboration between various specialties including oculoplastics, radiology, and neurosurgery for the successful management of patients with hemifacial spasm. Although hemifacial spasm is most often due to benign microvascular compression, a timely and accurate diagnosis is necessary to rule out ominous causes and coordinate future care. Clinicians should be familiar with hemifacial spasm and MRI studies should be promptly completed to confirm the diagnosis, identify etiology, and initiate appropriate treatment.

References:

- Anwar N, Nahar S, Anwar NB, Ullah AA. Understanding Hemifacial spasm: A Review Of An Uncommon Movement Disorder. Bangladesh Journal of Neuroscience. 2019 Jul 31;35(2):104-9.

- Banerjee P, Alam MS, Koka K, Pherwani R, Noronha OV, Mukherjee B. Role of neuroimaging in cases of primary and secondary hemifacial spasm. Indian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2021 Feb;69(2):253.

- Green KE, Rastall D, Eggenberger E. Treatment of blepharospasm/hemifacial spasm. Current Treatment Options in Neurology. 2017 Nov;19:1-5.

- Lefaucheur JP. New insights into the pathophysiology of primary hemifacial spasm. Neurochirurgie. 2018 May 1;64(2):87-93.

- Lu AY, Yeung JT, Gerrard JL, Michaelides EM, Sekula RF, Bulsara KR. Hemifacial spasm and neurovascular compression. The scientific world journal. 2014 Oct 28;349319

- Hovland, N., Phuong, A. and Lu, G.N., Anatomy of the facial nerve. Operative Techniques in Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery.2021; 32(4):190-196.

- Rosenstengel C, Matthes M, Baldauf J, Fleck S, Schroeder H. Hemifacial spasm: conservative and surgical treatment options. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 2012 Oct;109(41):667.

- Leong JL, Li HH, Chan LL, Tan EK. Revisiting the link between hypertension and hemifacial spasm. Scientific Reports. 2016 Feb 19;6(1):1-5.

- Miller NR. Eyelid myokymia. Surv Ophthalmol. 2011;56:(3):277-8.